Archive for the ‘Chinese seamen’ Category

A sailor’s life – 68. Pyrula and the seamen’s strike, Curaçao 1925

Curacao, St Annabaai – showing the growing Shell refinery and tanker port in the Schottegat, from http://www.hetgeheugenvannederland.nl

The Shell oil tanker Pyrula – formerly the White Star liner Cevic, ex Admiralty oiler Bayol/Bayleaf and one-time decoy battleship HMS Queen Mary – left New York on 21st August 1925 for a new life in Curacao in the Dutch West Indies.

She was manned by a mainly Dutch skeleton crew of 16, including three catering staff and four South American “firemen” (stokers) being repatriated to Maracaibo in Venezuela and Puerto Rico. The young master’s only officer – and the only other Brit on board – was his Scottish chief engineer, George Andrew of Airdrie.

Pyrula was a 30-year-old British steamer with a nominal horsepower of 708 and a working crew of 50, but after four years rusting off Staten Island as a floating oil depot for the Anglo-Saxon Petroleum Company, she faced a final journey of nearly 2,000 nautical miles (3,500 km) down the east coast of the US and across the Caribbean at the peak of the hurricane season, to a small Dutch island possession 40 miles north of Venezuela.

The voyage, the crew agreement notes, was to last for a period not exceeding six months and the sailors were to stand by until the ship was safely moored.

Rocky, dry Curacao was booming. The refinery had opened in 1918 and by 1925 beside the growing tank park, water plant and pending drydock, a little wooden Dutch town had sprung up with its own club house, tennis courts and golf course. Every four days a “mosquito fleet” of tiny tankers poured in from Venezuela with the oil bonanza discovered under shallow Lake Maracaibo, and by July the Isla was processing 5,500 tons of crude a day.

Shell oil depot ship Pyrula – formerly the White Star steamer Cevic, Admiralty oiler Bayol/Bayleaf and decoy Queen Mary

As the oil trade expanded internationally, increasing numbers of tourist steamers too were calling at Curacao, which was handily placed for the Panama canal and the Pacific, and Willemstad was starting to rival Amsterdam for ships and tonnages handled.

Once again,Shell needed Pyrula for bunkering. From the main harbour in the Schottegat lagoon she would eventually move out and round the coast, east to Caracas Bay, as a floating oil pump to the bigger ships unable or reluctant to traverse the narrow St Anna channel between the pretty Dutch gables.

And there she would end her career, overseen by a new master, Willem Hendrikse, and his growing family from a comfy stone bungalow built at the waterside. No more Shell wives made their homes among the old panelled staterooms of the former passenger ship, with their electric fans and bells to the pantry.

Shell tanker Satoe - former Monitor 24, from http://www.helderline.nl

Hendrikse would eventually have two retired British steamers in his charge. Satoe was one of eight shallow-draft Royal Navy Monitor-class gunships bought up by the Curacaosche Scheepvaart Maatschappij after the first world war. As Monitor 24, Satoe had seen service on the Dover Patrol in 1918 and in the White Sea in northern Russia during the allied intervention after the October revolution, but the “flat irons” as the Dutch called them, were so unsuited to the tropics that the Chinese stokers used to faint from the heat in the holds, he said.

No ship’s log survives in the tidy blue cardboard folder in the National Maritime Museum archives in Greenwich, where Pyrula’s particulars for 1925 have lain crisp and apparently unvisited since the merchant navy records were carved up in the 1970s. The two pages for certificates and endorsements are blank.

Lloyd’s List reports she was one of 13 ships to leave New York that day, and the only one bound for Curacao. So the first hint of anything untoward on Pyrula’s last long passage south is a single undated line on the front of the crew agreement, where her chief officer/acting master, Hubert Stanley Sivell, my grandfather, has added: “Vessel in tow and not under own steam” .

Arrived in Curacao “to be a hulk”, reported Lloyd’s baldly on September 8th.

Twenty-four hours later the men were paid off – in dollars. A small fortune in dollars: $744, worth £153 at the ambitious new exchange rate set that April by the chancellor, Winston Churchill, when Britain disastrously rejoined the gold standard.

Although Pyrula’s crew agreement was the standard UK form, with the usual pre-printed scale of provisions (a pound of salt pork on Monday, a pound and a quarter of salt beef on Tuesday, preserved meat on Wednesday, plus lime juice “as required by the Merchant Shipping act”) and the usual puny 5 shilling fines for everything from possession of firearms to mutiny, Bert’s sailors that trip were not on standard National Maritime Board rates.

Instead of £9 a month – a rate controversially reduced from £10 only that August, and still not including clothing, bedding or time ashore – the Anglo-Saxon Petroleum company paid Bert’s seamen an astonishing $62.50 a month. £12 15s. His firemen were on $67.50, or £13 15s.

In fact the chief steward, H Mulder, 25, who had signed on as humble mess room steward at $50 a month and been promoted to $120 a month before the ship even left New York, was earning only £2 a month less than the Old Man himself – although young Captain Sivell did not advertise the fact. The column for pay against his name in the crew agreement is prudently blank.

Over in North Shields, in the north of England, the British crew of the Shell tanker Acasta – which was shortly to arrive off Curacao to collect Bert Sivell and two other “spare” Anglo-Saxon officers and take them home – would have been highly interested in the pay aboard Pyrula.

Acasta’s pantry boy, 20-year-old Albert Black of Dene Street, North Shields, was on £3 10s a month. He took a £1 15s advance when he signed up, probably to buy oilskins and bedding as he was listed as a “first tripper”, and set up a £1 15s “allotment” to his mother, which left not much. In Tilbury, forty days later, he would be paid off with just nine shillings.

Throughout September seamen with families had run the gauntlet of pickets and opprobrium at dock gates and railway stations up and down the UK to sign on for the new low rate. There were 1.2 million registered unemployed that autumn, but on £9 a month even fully employed seamen found themselves needing to apply for “relief” between ships.

A letter to the editor from a seaman’s wife in Hull in July demands to know how she is expected to pay rent, insurance, coal and “keep respectable” on £1 6s 3d a week. “Now then, all you sailors and firemen, buck up,” she wrote, the night before the cut came in. “What do you pay 1s weekly to your union for, and never one word of protest from none of you? Buck up some of you. Scandalous such treatment for a British sailor.”

By the time Bert Sivell paid off his crew in Willemstad with their wedge of dollars in the second week of September, British shipping was in chaos.

There were pickets on wharves from Southampton to Glasgow, and unemployed men from Cardiff to the Tyne waiting in tugs in the Bristol Channel and off the Isle of Wight to make up numbers as ships sailed shorthanded.

Across the Dominions thousands of British seamen had walked off their ships – 2,500 in Sydney alone – leaving steamers, mail and precious perishable cargoes, including refrigerated meat, maize and 15 million oranges, laid up from Wellington to Durban SA. Thousands of seamen were camped in meeting halls and private homes, fed by the generosity of local families and unions, while the Australian and New Zealand courts sentenced hundreds at a time to jail with hard labour.

And all for the sake of £1 and a vote.

The dispute had begun very low-key on August 1st, when pay on British ships was cut overnight by 10% in an agreement struck between the shipowners and Joseph Havelock Wilson, the president and founder of the National Sailors & Firemen’s Union. It was the seamen’s fourth pay cut in four years, but there was no vote on it, neither for the NSFU membership nor for men in smaller unions not represented on the official national Maritime Board.

When the cut was announced there had been protest meetings and speeches. Letters to local papers outlined the long hours and poor conditions aboard British ships (“only fit for seamen of an Eastern nation…”) and in Hull a disorderly NSFU meeting carried a vote demanding Mr Havelock Wilson’s resignation, which the union officers ruled out of order.

On “Red Friday”, July 31st, as the coal and rail unions were celebrating victory over the government of Stanley Baldwin, 200 seamen in Hull voted to strike.

The miners and railway workers were big hitters who had threatened a general strike over the mine owners’ plans to cut pay, (which was £3 a week in Staffordshire and up to 13s a day in Scotland) and faced with the prospect of the country being brought to a standstill Baldwin had backed down. He agreed to subsidise the industry for nine months, pending an inquiry (- which would lead to the general strike in May 1926, when the royal commission came back with a recommendation to cut the miners’ pay anyway, but by then the government had emergency plans in place – and volunteers on standby to drive buses and trains.)

But there was no similar support for the seamen. The NSFU stood by its sweetheart deal with the shipping companies, so the TUC – and even the breakaway Amalgamated Maritime Workers’ Union – considered the action “unofficial” and would provide no fighting fund. Within weeks, seamen refusing to sign on at the lower rate were deemed “unavailable for employment” and cut off from the dole.

Newspaper reports of the meetings of the workhouse guardians record debates about basic food relief, to prevent the wives and children of strikers “actually starving”. The men, it was agreed, should get nothing.

On August bank holiday weekend the Hull Daily Mail’s man at the dockside described the crowds of happy day trippers who piled unmolested onto the steamers Whitby Abbey and Duke of Clarence, despite the seamen’s strike. “There was no disturbance beyond a fight between two small dogs; a policeman on duty yawned continually, apparently bored with the inactivity of the ‘strikers’,” he sneered.

Up and down the country for the first three weeks of August ships sailed, and wherever men refused to sign on at the lower rate there were plenty of others hungry take their places.

Times were hard. The first world war had cost Britain her export markets. As the chancellor, Winston Churchill, wrestled with reparations and repayments, his overambitious return to the gold standard was having a depressing effect on Britain’s balance of trade. (Nations united by the gold standard, he had said that April, would “vary together, like ships in harbour whose gangways are joined and who rise and fall together with the tide…” Eurozone countries please note.)

Struggling to compete on price, British manufacturers cut pay. And kept cutting.

Even on the Isle of Wight unemployment was rising, from 1,000 in January 1925 to 1,538 by Christmas, but the situations vacant column in the local paper there (mainly seeking servants) was still three times the length of the situations wanted. Niton needed a gas lamplighter, the County Press reported, and a married woman teacher in Dorset had won a ruling in Chancery preventing the school governors terminating her employment, “even though there were single women teachers wanting for work”.

Seamen were largely casual labour, and even on £10 a month often could not lay enough by to feed, clothe and house a family during the growing gap between ships. To strike against the NSFU, cut off both from unemployment relief and union support, meant hardship.

By the middle of August it looked like the strikers might be starved out. But industrial relations took an unexpected turn when the first British ships started arriving in Australia after the three-week passage, and an energetic seamen’s union recently victorious in its own battle over pay and conditions took up the cause.

By the time Pyrula arrived in Curacao, the strike had taken a grip in the UK itself.

“Two thousand three hundred passengers, practically all Americans, booked to sail tomorrow morning from Southampton to New York on the White Star liner Majestic were at their wits’ end today,” the New York Times correspondent TR Ybarra cabled on September 1st, “trying to find out whether the Southampton seamen’s strike would force the Majestic to postpone her sailing.” Bristol, Hull and Liverpool were also affected, he said.

In South Africa, desperate fruit growers clubbed together to pay the disputed £1, just to get their oranges away. “The fruit interests are emphasising that for a matter of £70 in wages in this ship Roman Star £300,000 worth of fruit is being jeopardised, which if lost, will mean the ruin of many small producers,” the Western Morning News reported.

In Avonmouth, 30 boilermakers working on an Eagle Star tanker in dry dock downed tools. The San Dunstano needed enough work to keep 300 men employed until Christmas, they said, but they were being asked to just make her seaworthy to reach Rotterdam, where the Anglo-Saxon Petroleum company had already sent the US-built Ampullaria. With 400 men locally unemployed it was “not right to send three months work to the Continent”.

“A MILLION TONS HELD UP BY SEAMEN’S STRIKE”, shrieked the NY Times on the 17th.

With the country’s maize and citrus exports rotting on the wharves, the South African government tried to mediate – mooting a six-month inquiry, as put in place for the miners, but the shipowners said no. Union Castle began to recruit “lascar” crews in Bombay, but India and South Africa both protested – though for different reasons.

As well as their £1 back, and paid overtime, and an end to the NSFU’s closed shop deal with the ship owners, the strikers wanted a ban on cheap Chinese and “lascar” crews.

Asiatic seamen in the Strangers Home, West India Dock, London. Memorial University Newfoundland website

Wartime restrictions on enemy aliens living in the UK had been extended after the war, limiting employment rights for foreign nationals and barring them from certain jobs (including the civil service). The act had particular impact on foreign seamen working on British ships, and was encouraged by British trade unionists fearful of the cheap competition for jobs. [It was expanded again in 1925 by the Special restriction (coloured alien seamen) order, and even more shamefully not repealed until 1971]

Under so called “lascar agreements” big British firms like Union Castle signed up Asian crews as a job lot for a round trip, under a serang. They did not have to be paid British rates, because they were not signed in British ports, and they were expected to put up with grossly inferior conditions for reasons that can only be described as racist.

Acasta’s white British crew had themselves taken the place of 38 Chinese seamen and firemen who were signed off in South Shields on September 10 after 11 months’ service between Trieste, Malta, Panama, Montreal, Las Palmas and Marseilles.

These men were all registered to boarding houses in the same three streets in Rotterdam – Atjehstraat, Delistraat and Veerlaan, and their pay per month of the trip cost Shell even less, an average of only £3 a head.

Many Chinese had appeared in the tiny docklands peninsula of Katendrecht in 1911, signed up in secret by Dutch ship owners as strikebreakers to work the big passenger liners to and from the Dutch East Indies. They had no unions, only “shipping masters”, who allocated ships and rented beds in their boarding house between jobs.

The Chinese had a reputation as hard workers. They did not drink, were docile with their pipes and mahjong (“less troublesome than a white crew,” said Bert), and were willing to work for little pay.

They were also expected to eat less than a white crew, according to a typed “Scale of Provisions (Chinese)” tidily appended to Acasta’s crew agreement by Captain G. Croft-White. Although the same document shows fireman John Sow had to be left behind in hospital in Marseilles that trip suffering suspected beri-beri.

Shell’s Chinese seamen were entitled to 7lbs of beef, pork or fish each per week, against 8lbs allocated for white crews, and they got 10 and a half lbs of rice, instead of 11lbs of potatoes, biscuit, oatmeal and rice. They got less coffee, marmalade, bread, sugar and salt, more tea and dried vegetables, and no dried fruit, suet, mustard, curry powder or onions at all.

Capt Croft-White was clearly a belt and braces sort of chap, for above the scale of provisions is also gummed a paragraph from a printed document outlining the National Maritime Board’s absolute jurisdiction over pay board his ship, including its ability to retroactively impose cuts.

“It is agreed that notwithstanding the statements appearing in Column 11 of this Agreement the amounts there stated shall be subject to any increase or reduction which may be agreed upon during the currency of this Agreement by the National Maritime Board …”

Bert spent a month in Curacao, handing over and sorting out paperwork, but no letters survive. Only Acasta’s crew agreement shows that he was picked up “at Sea” on October 20th with two other British officers from Dutch lake tankers, and conveyed home to Tilbury.

He arrived back in Britain in November 1925. The strike was over. The seamen had lost.

From Australia came reports of violent clashes between police and British strikers in Fremantle, but after 107 days the men there too gave up and started trying to sign up for a ship home.

It was the loss of trade that eventually beat the seamen’s strike, as farmers and woolmen facing ruin eventually turned on the cuckoos in their nest. Lost, delayed and diverted trade was estimated to have cost £2 million. The shipowners claimed it was a Red Plot.

On December 8th, the Western Argus in Kalgoorlie, Western Australia, ranted: “The anti-British character of the strike was plainly shown by the action of the agitators who fomented it in Australia. They professed sorrow and indignation over the unhappy British seaman, compelled to starve on a miserable pittance of £9 a month, but they said nothing about the German seamen working for £4 4s. All their efforts were directed to holding up the British shipping trade, while foreign vessels were allowed to come and go unhindered…”

After more than four years away Bert hurried home the Isle of Wight for a rare Christmas with the wife he had not seen for a year and the baby daughter he had never met at all. His furlough pay as chief officier was £24 10s a month.

Read on: In Memoriam

Previously: Cabinned, cribbed, confined

A sailor’s life – 66. The Clam, a moment in history

“The old Clam is up to her tricks again: early this week she decided to take a sudden list, after standing perfectly upright for over two months. We had to chop through a foot of frozen snow and ice to get to the tank lids and then we had to use a crowbar to get them open. She was not leaking, so I do not know the cause of her latest crankiness.”

Bert Sivell, officer-in-charge Shell depot ships Pyrula and Clam, New York, January 1925

In the winter of 1925, the East River in New York froze, trapping the ferries. One morning Bert Sivell found he could almost walk from his home on the former passenger liner Pyrula at Stapleton NJ to his support tanker, the 3,500 ton Clam, across the ice that stretched half a mile into the bay.

The steam was off, there was no oil cargo aboard either vessel, and no ships calling for bunkers. The Anglo-Saxon Petroleum company (fleet arm of the 1907 merger of Royal Dutch Petroleum with the “Shell” Transport & Trading co.) was shedding its old tankers and both vessels were up for sale – for £25,000.

Pyrula was just an old passenger steamer, converted to an oil tanker by the Admiralty during the first war when she had seen action as a dummy warship, but Clam – though older – was a pioneer: a bit of Shell history.

The Clam was a proper oil tanker, purpose-built to carry lamp oil in bulk a decade before the word “tanker” was even invented, in the days before ordinary householders could dream of electric lighting and when gasoline was still a worthless byproduct being run off into rivers from Pennsylvania to Azerbaijan.

Launched in 1893, the Clam was older than her newly-wed young officer-in-charge, and older even than the old square-rigged sailing ship in which he had served his sea apprenticeship.

She was the last of the very first “Shell” tankers; the fourth of four sister ships designed in secret in 1892 to challenge the monopoly of American oil and its “Octopus Standard Oil by carrying Russian kerosene in bulk to the burgeoning markets of the East through the Suez Canal.

Murex, Conch, Turbo and Clam were a sideline to the rice and case oil business of a self-made British family, the Samuel brothers; a bow drawn at venture, rather like the workshop Samuel senior had founded, sticking exotic shells on tricket boxes for the booming Victorian seaside souvenir trade.

They were not the first purpose-built bulk oil tankers* – a distinction that belongs to either the Belgian Vaderland (1872), the Swedish Zoroaster (1878) or the German Gluckauf (1886), depending on your definition – but they had reinforced bulkheads up, down and across creating multiple separate tanks; cofferdam “buffers” fore and aft, isolating the fiery boiler room and coal bunkers; and expansion tanks to contain the expanding cargo in hot weather and prevent it shrinking and lurching in cold. They had water ballast tanks, to empty in case of grounding; electric fans to expel explosive gas vapours; integral pumps; and steam pipes for cleaning between wet and dry cargoes (!) – for purpose-built or not, the Samuels could undercut the competition if their oil tankers carried a cargo of tea back.

The ships were leak-proof, collision-proof and as far as possible fire-proof, and in August 1892 Murex made history as the first bulk oil carrier ever to pass through “the ditch” and into the Red Sea, bound for Thailand. She carried with her a little murex shell, presented to the master by Marcus Samuel from his own collection.

The Samuels were not Rockefellers. They were Whitechapel Jewish importers of rice and grain, semi-precious stones and shells, but they had inherited a network of trading agents across the far east and together they set up a syndicate to build onshore storage tanks that eventually stretched from Shanghai to Batavia (Jakarta), and from Bombay to Kobe. They worked in secret, because the ruthless Standard Oil had ways of seeing off competition – until it was finally forcefully broken up by US anti-trust laws in 1911.

Gradually, the eponymous rusty blue-green of Devoe’s Brilliant case oil tins – which had built itself into the very fabric of villages across the East as raw materials for everything from roofing tin to toys – gave way to shiny red ones, manufactured on the spot, and in 1897 the Samuel brothers struck oil of their own, in eastern Borneo, north of an unspoiled little fishing village called Balik Papan – (now an oil city of half a million souls.)

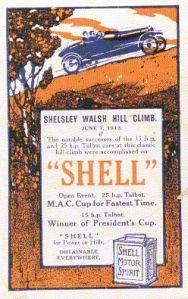

Shell oils advert for the Shelsley Walsh Hill climb 7 June 1913. Sir Marcus swiftly allied his products with pioneering motoring and aviation attempts

The following year, when the “Shell” syndicate began converting its tank steamers to burn its own thick fuel oil, Clam was first.

By 1925 only the Clam was left. Conch was wrecked off Sri Lanka (Ceylon) in 1903; Turbo went down in the North Sea in 1908; Murex was torpedoed outside Port Said in 1916. But the Clam – requistioned by the Admiralty for service as RN oiler No. 58 and torpedoed in the Irish Sea by UB64 – limped into port and returned to work.

By 1925, there had been a hundred and twenty-seven “shell” tankers, including Murex (2), Conch (2) and Turbo (2). Marcus had been knighted for services to the Admiralty, and then raised to the peerage as Lord Bearsted. The “Shell” syndicate had merged with the Royal Dutch and oil was big business from Indonesia to Venezuela, producing all manner of oils, thick and thin, including the once despised gasoline and new aviation fuel.

The Clam was an antique – old and cranky, flip-flopping at her moorings in the ice and fog off New York, minded by a young officer-in-charge apparently whiling away his time with prize crosswords and letters to his wife far away in the UK, and a young engineer juggling three girlfriends. (“… He met them at a dance hall he goes to. He takes them all out on different nights and has been buying them presents too. I think they are soaking him good…”)

America was still supposed to be “dry” and at Christmas the manager of the Asiatic Petroleum co. [Shell’s management arm] had brought them a basket of fruit and some cigars, which Bert shared with his last few Chinese sailors. “Their forecastle will be all right tonight with cigar smoke and opium,” he commented. He saw in the New Year out at the moorings with Clam, listening to all the ships around him rattling their whistles. (“Not a sound from Pyrula, not even the bell.”)

Up in New York, the Ford Motor company was pulling crowds with a two week exhibition at its showroom on 54th and Broadway, where you could watch twenty-five workers assemble a motorcar they themselves could afford to buy – start to finish in 20 minutes flat.

Bert joined the gawpers. “They build them on a moving conveyor,” he wrote. “The men never move from their positions but just do their bit to each machine as it comes to them. Finally the machine rests on its own wheels and they start the engine and drive it away. It really is a wonderful piece of organisation.”

The (free) show included entry to a prize draw to win your own car. Bert managed three trips, and three entries to the draw. He was already scouring the local paper his parents sent him for a house with a garage. “I made up my mind some time ago that I would have a car during the first leave after I go master.” That would be 1928, by his calculation.

Although he had passed his master’s ticket in 1919, promotion in the “Shell” depended on seniority. Every company man kept a jealous eye on the men above and below him on The List, and the only bearable part of the drudgery and boredom of minding Pyrula and Clam that final year was the fact that it all counted. “The old idea about sea experience is dead in this era of steamships,” he grumbled, ungratefully.

Once a week he left the pier and caught a vaudeville show off Broadway. “There’s a new idea at the Liberty now,” he wrote in January. “On Monday and Tuesday there is no vaudeville, but two pictures (movies) instead, admission 25c and 35c. Wednesday night is Opportunity night when the local talent give the vaudeville and prizes are awarded by the audience’s applause. We get the two pictures as well, admission 40c over all. Some of the local talent is terrible.”

Once a week he lunched at Yeong’s Chinese restaurant, where he would listen to the jazz bands and watch the dancing, wandering back to Pier 14 via the bookshop on the eighth floor of Wanamaker’s in Washington Square.

The American Sugar refining company turned up in February, looking for a Cuban depot ship “if the price was right”, followed in March by two more Italian gents (“because they gave me a cigar”) and a firm of Danish ship breakers. Both made offers and both sought Bert’s services as master to sail and tow both vessels back to Europe. But the Anglo-Saxon said no.

It said no again when a German shipbreaking firm in Hamburg bid £23,500. (“As luck would have it we were both in our overalls and pretty black. I have all the boats turned inside out and Andrew has part of the main engines adrift ready to go to sea, so we had quite a decent show for him.”)

By now six of the war generation tankers had been sold that Bert knew of: Caprella (ex War Gurkha), Conia (War Rajput), Melona (Elmleaf), Prygona (Aspenleaf), Strombus (RN oiler 4) and Cardium. Bigger ships were on the stocks. Bert boxed up four years of clutter and destroyed all Ena’s early letters, ready to go home. And nothing.

The baby was born in March, but in April he was still showing prospective buyers around Pyrula and Clam, without success. “It is pretty evident now that the ASP have abandoned the idea of selling these ships for operating tonnage and they are now looking for the best price for junk.”

The Clam was eventually sold to Petrolifera Esercizi Marittima of Venice in 1926 and renamed Antares. The following year Shell launched a 7,400 ton Clam (2). Pyrula was moved to Curacao, still as a depot ship, and scrapped in 1933. Antares/Clam outlasted them all. She finally ended her long career after she was torpedoed by the Italian submarine Alagi in 1942. She was refloated but scrapped the following year.

By then, Bert was dead. He never did get his motorcar.

Read on: Maybe baby

Previously: Homeric and the Raifuku Maru

* In 1861 the first recorded ship to carry (US) oil in bulk, the tiny two-masted sailing ship Elizabeth Watts, sailed for England with a drunken, crimped crew – no sober volunteers having been found willing to risk their lives with such a hazardous cargo.

A sailor’s life – 59. In sickness and health, 1921

Suez to the Shatt al Arab light vessel took the oil tanker twelve days nine hours and they arrived in the mouth of the Euphrates at 2am on 19 May 1921. “We have seen nothing but sand – mountains of it, since we left,” Bert wrote, as they waited for the pilot to cross the bar. “When daylight came in I looked round for the land but failed to see any. The surrounding country is flat and swampy and the lightship is too far out to see it.

“I suppose we had been going again for an hour and a half when I looked out and saw land – and to my utter astonishment everything was green with plantations of date palms. However, as the two banks converged one could see that the green only lasted for a mile from the water’s edge. In fact, at Abadan it is less than a hundred yards wide.”

Bert Sivell, chief officer of the Anglo-Saxon Petroleum oil tanker Mytilus, was ill. For a month he had lived on beef tea and milk. He’d seen a doctor in Suez, and in Abadan the 2nd mate was sent ashore to fetch another, a dour Scot from Aberdeen, who diagnosed a kidney infection and issued the master with a letter to the Anglo-Saxon head office in London, prescribing two months sick leave. Bert’s letter is sprinkled with exclamation marks, but he knew he wasn’t going home. They were three months out of Rotterdam, and relations between Captain Hill and his 1st mate were at an all-time low.

“Captain Hill has funny little ways,” Bert had commented, as they crossed the Mediterranean in vile weather. He wanted four star observations left on the chartroom table each morning, to work out the ship’s position for himself. But Bert left them with the maths done, “to show him I could.”

Then there were the charts, which Hill would let no one but himself touch. “Personally, when we are going along near land I like to take cross bearings now and then, lay them off on the chart and see if the vessel is keeping her course properly. That is as much for the safety of the ship as anything else. But the first time I put bearings on the chart I was told about it, so after that I used to call him up about twice during my watches, to take bearings. He soon got tired of that and has now given me permission to not call him unless the ship is out of position. The 2nd and 3rd have not that authority, so apparently I have scored a point.”

The Rock of Gibraltar had been invisible through the rain and the oil tanker had to heave to for 24 hours level with Malta – bows into a gale, battered by hailstones, engines on full ahead. “Talk about the blue Med…” Bert snorted. But it meant the painting wasn’t done.

In the narrow Suez canal south of Port Said, Mytilus got stuck, blown into the bank as they gave way to laden tankers coming the other way. They ran ropes ashore and tried to heave the ship off, but the wind was too strong. “After about an hour of this I got tired of it and wandered along to the bridge to suggest pumping some ballast out of one of the forward tanks, to lighten her nose and clear the bank that way. It struck me as rather strange that the order had not been given from the bridge as soon as she struck, especially as the old man has been in tankers for years…”

Postcard view of the Suez canal - 'It is nothing very wonderful after all: very narrow, two vessels cannot pass, and surrounded by low sandhills' Bert Sivell 1921

They remained tied up all night, further battered by a sandstorm. By Suez, there was a huge row. Bert was running a fever and the master said Mytilus was a “—-ing pigsty”. Bert had been saying it himself for a fortnight, but he didn’t relish the reprimand. A chief officer was responsible for the painting. The tanker looked all right from a distance, he wrote, after an afternoon in the ship’s boat, teaching the apprentices how to row.

There was a strike at the refinery in Ismailia, and ship’s crews were doing the pumping. While Captain Hill and the chief engineer disappeared off to Cairo to see the pyramids, Bert saw a doctor, who diagnosed sunstroke. There were half a dozen Shell ships in port, and his old master, Captain Harding, dropped by. “It was quite like old times to have him sitting in my room for a yarn. He is so different to the one we have now. I got quite a lot of news from him.”

From Suez, Mytilus went north again, to Marseilles, another bad passage. Bert was still ill. In the desert canal all his new paint got covered with fine red sand several times and rough seas in the Med took off what was left. They arrived in France streaked with rust …

In Marseilles the benzine pumping station they were hooked up to 500 yards away exploded in flames, killing the pumpman, and Mytilus had to be yanked off the wharf by Acasta, which had fortunately been discharging fuel oil just outside the benzine dock. Bert shut down in a hurry, disconnecting the pipes and moorings, raising steam and all the while keeping the water hoses plying the main deck, to keep the temperature down. “If we had gone on fire it would have been goodbye Marseilles, town, docks and everything.”

They shifted to St Louis de Rhone, on the Camargue marshes. It was a dead show, he said. Just a village. But then he had been discharging day and night since they arrived and had not been ashore, so could not tell. Shell’s superintendant had been aboard and complimented him on “having one of the cleanest ships in the company”, he reported wearily. He spent 19 hours on his feet on his birthday, and they were delayed again when the mistral blew them into the canal bank.

The gossip from France was not good. Bert’s pay had been cut by £2 15s a month, and the superintendent said forty ships were being laid up. Tucker, Bert’s predecessor as chief officer on Mytilus, who had left to be master of War Patriot (Adna), had had to revert to chief officer again – the second time it had happened to him. “Things must be pretty serious when a firm like the ASPCo are laying up their vessels because they have no work for them.”

He was taken bad again in Abadan, and burning up as they crossed the Red Sea heading for home again. He was still not eating, and one night the captain had to take half his watch. By Suez, Hill threatened to put him ashore, and by Gibraltar he said Bert would never get another ship again, “in this company or any other.” Off Spain they fell out over the colour of the regulation paint.

“The men have worked well but the weather has been against me – my usual luck again when painting the ship,” wrote Bert. “Last Monday was fine, so we painted down the masts, funnel and adjacent ventilators. That was a very good stroke of work. I am afraid a present day ‘white’ crew would not do as much. Tuesday was also fine, and we painted right round the bulwarks – another splendid stroke. They lost two days to bad weather and then on Friday, being some Chinese holiday, the crew did nothing, and it was a beautiful day too. Then Saturday was a half day but I managed to get a little done and that ends the week.”

Captain Hill and his ailing chief officer parted company in Lisbon in June, Bert leaving for the UK bearing in his pocket a terse letter of “reference”. (“Mr HS Sivell has served on board the SS Mytilus as chief officer from December 1920 to present date and is now going on leave. Conscientious in his work, his services have been quite satisfactory.”)

He was braced for a long wait for the next ship or perhaps demotion to 2nd mate, but by August he was in North Shields, fully recovered, and signing on as chief officer with the Shell tanker Euplectela on £26 8s a month – with a view to joining the depot ship Pyrula in Barcelona on £28 12s and remaining with her to New York, where he would become officer-in-charge on £35 a month. It would be his first command.

Ya boo sucks, little Hill.

Read on: Ships that pass in the night: Stanley Algar

Previously: Spoils of war

blogroll

A sailor’s life – 58. Spoils of war, 1921

Bert Sivell saw in New Year’s Day 1921 in drydock in Rotterdam, as officer in charge of the Shell oil tanker Mytilus – surrounded by the company’s new “war” boats having their names changed to shells.

Absia was there (ex War African), and Anomia (War Expert), and Marinula and Melania, and the four-masted Speedonia. The War Rajput (soon to be Conia) was due in and War Matron (Acasta), and his first ship, Donax. His last one, Orthis, had just sailed.

“There’s a big slump in cargo steamers just now and many are laying up, but ours cannot get around fast enough,” he wrote. In Britain, a national coal strike had erupted in October.

“No dear, the coal strike will not delay our docking,” he had written to Ena when it started. “It has done something far worse: it has driven the job out of this country altogether. Did you read in the paper a day or so back about a big ship repairing contract being transferred from North Shields to Rotterdam? That was this firm. They had five Monitors at Shields, being converted into tankers*, but owing to labour troubles in the ship yards and coal mines they towed them over to Rotterdam to finish converting. Think of the amount of work going out of the country, and the money…”

Britain had emerged from the first world war millions of dollars in debt to the US and with its overseas markets in tatters. Pent up domestic demand masked the damage briefly, but as the men poured home to their civilian jobs, suddenly there were too many men and not enough jobs. Wages began to slip. During a flying trip home in January with the ship’s accounts, Bert passed down Oxford Street on the breezy top deck of a double decker bus and noticed various groups of unemployed ex soldiers including a band of veterans busking for pence outside Selfridges. Trade was bad, he noted.

But out along the Heijplaat in Rotterdam business was booming. Tiny neutral Holland had emerged relatively unscathed from the war between its big neighbours – give or take the thousands of Belgian refugees and the rationing and the Spanish ‘flu.

Heijplaat, Rotterdam - "Half garden city, half dockyard", opened in 1920 with 400 homes, three churches, a public bath house and a 'dry' cafe (Photo 1960s)

Bert had arrived in the Netherlands aboard Orthis in December, still dodging sea mines and funnel still sparking “like a Chrystal Palace display”. He saw in the new year from a pontoon in the Maas, on the wrong side of the river from the centre of Rotterdam. The Dutch kept up new year properly, he reported, all work having stopped at 1pm and not due to restart until Monday. Cafés, bars, picturehouses and theatres were all open, however, and there were lively crowds on the streets, including several fights, which he dodged. “I did not fancy a night in jail.” He did not like Rotterdam, nor the Dutch much.

Within weeks, however, the harbour was heaving with Shell ships and Bert found himself surrounded by new ships and old friends. “I have just had one of the best weekends since I have been in Rotterdam,” he wrote.

“In my last letter I told you that the four-masted barque Speedonia belonging to this company had arrived. Naturally, being fresh out of sail myself, I was interested in the vessel, so on Saturday afternoon I went round to her. I just drifted aboard casually and saw a man holding up the cabin doorway. It struck me I should know him so I started to yarn, and in the course of our conversation I tumbled to where we had met: he was 3rd mate of the four-masted barque Grenada and we were together in Newcastle NSW in July and August 1913, and again in Gatico and Tocopilla (Chile) from October to December of the same year. I had not heard anything of him since. We went ashore together on Saturday evening and I piloted him round the sights.

“Sunday morning I was busy doing accounts when the Donax appeared on the scene. Naturally there was no more work that day and after dinner [lunch. Ed] I dressed and went round to her. She was lying at the installation, only about a mile away as the crow flies, but five miles when one has to walk it. It was a lovely day and I quite enjoyed the walk. I got round about 3.15pm and strolled along to the messroom, where I found the chief engineer playing draughts with the Marconi operator. He was very surprised to see me, because they all thought I was still on the Orthis. We adjourned to his room and give each other all the news and then the Chinese boy came in with the chief’s tea. He nearly dropped the cup when he saw me and got a ‘ten cent’ wriggle on to bring me one. After about an hour with the chief I blew along to see Captain McDermid.

“When passing through the saloon I ran into my own former boy. His face broke into a big oriental smile immediately and he started bowing and saluting alternately. It was really very amusing. Then I got into the old man’s room and his first question was if I was married yet. We had a long yarn about everything and he fished out a bottle of port.”

Captain McDermid said Shell was negotiating building forty more Donax-type ships in the US (“just think of the masters’ jobs”) on top of twenty-six already under construction at yards around the world. Thirteen were due to be commissioned that year, he told him.

McDermid was senior Shell man and he predicted great things for Bert; the company’s eye was on him, he said. Sailing ship qualifications were the golden ticket.

But Bert’s rapid progess had not passed unnoticed lower down the pecking order either. The 2nd mate on one of the other tankers challenged him to his face: why was Bert chief officer on a bigger ship after only 18 months in the company?

By late February, when Mytilus’s new master Captain (“Little”) Hill stepped aboard, Bert had been in Rotterdam for four months and he was ready to go, but it was still a shock when the orders came for Abadan.

Read on: In sickness and health, Mytilus 1921

Previously: The wife’s tale II

*Renamed Anam, Ampat, Delapan, Doewa, Lima, Tiga, Toedjoe and Satoe

A sailor’s life – 54. Flaming funnels, Orthis 1920

“This morning a box arrived on board marked ‘fragile’ and on opening it what do you think I found? A glass case containing a couple of Orthis shells mounted on a piece of pearl and the vessel’s name engraved on another piece of pearl, the whole lot set off on blue plush. All the ships of the fleet have a similar case. It is supposed to be placed on the saloon sideboard, but as we have no saloon it will have to go in the messroom.”

26 May 1920, Millwall dock, London

The Shell tanker Orthis started life as the 1,144 grt creosol class harbour oiler Oakol, bought cheap from the Royal Fleet Auxiliary during the oil group’s post-war shopping spree in 1919.

Named apparently after a Paleolithic fossil by someone in the company with a sense of humour, Orthis was small and scruffy, a dwarf against the purpose-built Donax and a fleabite to the 18,000 tonners being built in the US for Eagle Oil. She was a mess, and as new first mate it was Bert Sivell’s job to knock her into shape, supervising the new Chinese crew painting her into the company’s livery, and scouring and steaming the tanks until they were clean enough to carry benzene.

“What d’you think to the old yacht?” the marine superintendent at Shellhaven had said, inspecting the vessel in June 1920, after a month’s hard graft. For once Bert was tactful, blandly ignoring the little ship’s tendency to shoot flames out of her funnel, fifteen or twenty feet high, which the refinery staff seemed to find unnerving.

(“The shore people will not let us run our dynamo now in case a similar thing should happen, so we have to stop pumping at 9pm before we can have lights aboard.”)

In two years flat the company was to snap up 32 surplus vessels, ranging from ex-RN oilers and dry goods carriers built for the Admiralty and the wartime Shipping Controller, to an old Canadian train ferry (Limax) and two halves of a refloated wreck (Radix). The Anglo-Saxon Petroleum Co. alone bought sixteen of the 416 government-commissioned “War” range of standard ships, six of the emergency wartime construction “Leaf” freighting tankers that had had to be put under civilian management because of the US neutrality act, and several former RFA “Ol” oilers, including little Orthis-Oakol.

By late 1920, these ships were starting to take their places in the burgeoning Shell fleet: War African became Absia, War Expert the unlovely Anomia (“Captain Cass her skipper says he’s going to call her Amonia, it’s the only way he can remember it…”), Aspenleaf, Briarleaf, Dockleaf and Elmleaf became Prygona, Lacuna, Litopia and Meloma, – the biggest of them only 7,550 grt.

Meanwhile, Orthis’s engineers had spent the early summer twiddling and tweaking in Millwall dock, trying to tame the old oiler’s combusting engines and wayward steering gear. (Judging by the dents in her hull, a long-standing problem, Bert mused.) He didn’t repine though. Twice he managed a dash to see his parents on the Isle of Wight, once whisking Ena with him on the night mail; twice he managed a snatched evening with her in Tunbridge Wells after work, arriving at 6pm and running for the London train again at 10pm; and at Whitsun they achieved one glorious sunny weekend in each other’s arms on the cliffs at Minster, where two weeks later he was sluicing the last of a load of dirty benzene out of his tanks into the Thames in a way that would give modern marine authorities a fit.

Twice Orthis went to Rotterdam too, but all he ever saw was the tanks of the installation. “There was a little village about ten minutes walk from the ship, but it was not worth while going ashore,” he wrote. “In any case, I have quite enough to do on board. I still have an awful lot of writing as well as the ordinary work of running the ship and her crew and in addition I have to look after the victualling of the ship for which I receive the large sum of £3 per month as an extra.”

With that and the £3 war bonus and overtime, he was earning per month about three-quarters of what Ena earned per year – £40 making hats. Shell paid well.

In June they went to Helsingfors (Helsinki), via the Kiel canal, still dodging sea mines even in the North Sea but now with the added hazard of the erupting funnel.

“Just before entering Holtenau lock at the Kiel end of the canal our funnel went afire at 1am and being a pitch black night of course everything was well lit up by the glare. All the Germans in the vicinity, including our pilot, got the “wind up” badly, but we are getting used to these little happenings. They are quite harmless as long as no benzine is about.”

On the return journey, while navigating Brunsbuttel lock, another eruption managed to ignite one of the lifeboats. “We caused great excitement among the shore community,” wrote Bert.

After Finland, when Bert and Captain Harding enjoyed two illicit evening trips ashore together, listening to the bands in the park, visiting the zoo, and not getting back to the ship until 1am – “when it was still light enough to read a newspaper” – the real work started. Up and down they ran to Hull and Granton, outside Edinburgh; 45 hour trips, pumping as soon as they were alongside and sailing again as soon as they’d done. Bert barely got his clothes off and the overtime was ratcheting up nicely, but there were no flying visits to Tunbridge Wells, just more paperwork for dented jetties – and an inquest.

(En route back from Scotland a fire had broken out in the “European” galley, fatally injuring the Chinese chief cook. They swung the tanker into the wind to prevent the flames spreading and Bert doctored the all-too conscious victim with carron oil and opium, swaddling him in wadding, lint and sheets. But the poor man was too far gone. The tanker put back into Leith, and the cook was ferried ashore in a lifeboat, and Bert went with him in the horse drawn ambulance over the cobbles. But the doctor said it was a hopeless case. An enquiry ensued.)

“My dearest sweetheart, I am so sorry you only had one letter from Thameshaven but on these short runs I don’t seem about to fit in the time for much letter writing. We were only 15 hours in Hull and a few minutes under 24 hours at Thameshaven, so you can imagine how much spare time the ‘poor’ mate gets after he has finished with cargo and the thousand odd jobs in getting ready for sea again … The spring-clean is going on very, very slowly. It will be some weeks before I can make this thing look anything like one of the ‘Shell’ line vessels and I expect as soon as I have finished the job I shall get a transfer to another old rattle box.”

The transfer when it came, came quickly. In December 1920 Bert was appointed acting chief officer of the 5,000 tonner Mytilus. Captain McDermid of Donax, whom he met in Rotterdam that January, took all the credit and fished out a bottle of port to celebrate.

“He told me that when I was with him he had had special orders to watch me and report back accordingly. He says Donax is altogether a different ship since I left.” Shell was negotiating the building of 40 more Donax-type ships in US, according to McDermid – on top of twenty-six (he said) already under construction all over the world. Thirteen were due for commission that year. “Think of the master’s jobs…”

McDermid predicted Bert would be master himself in three years.

Read on: Dublin and the troubles, 1920

Previously: Christmas at sea, Donax 1919

Work in progress: the book I never wrote about the sailor grandfather I never knew, from apprenticeship on the square-rigger Monkbarns to death by U97

Blogroll

A sailor’s life – 49. Clan Line, or Shell?

Bert Sivell, formerly Mate of the sailing ship Monkbarns, joined the Anglo-Saxon Petroleum Co (Shell) in autumn 1919 with a crisp new Master’s ticket in his pocket barely a fortnight old.

He was 24, with hands-on experience of shipwreck, war and mutiny, but he signed on as humble 3rd mate in the oil tanker Donax for £18 5s 6d a month, ”all bedding, linen and uniform accessories to be supplied by the Company”.

He had arrived back in Britain just in time for the national peace day celebrations that July – parades and bunting and industrial unrest. After nine years at sea studying by kerosene lamp between watches, sitting scrambled tests in ports around the world for hurried promotions, he was to spend some weeks with his parents on the Isle of Wight, attending college on the mainland each morning, and relaxing at the weekends cycling through the country lanes or tramping miles across the chalk downs with friends. (“Girls, of course,” he wrote to the girl who would be my grandmother.)

When he graduated top of his class with 89% marks after seven weeks, he was offered a job immediately, as 4th officer on a steamer departing for India that night. But he turned it down, saying “he was on holiday and had a few more girls to see.”

He posted off an application to the Clan Line of Glasgow, a comfortable, regular passenger-cargo steamship service to India, and then kicked himself when the Clan’s job offer finally caught up with him in Rotterdam two weeks later, in what was to be the first of many thousands of dreary out-of-town Shell oil refinery berths. But he didn’t repine at taking Shell’s shilling. Or not much.

The wave of national rail and coal strikes that racked Britain that summer almost as soon as the celebration bunting came down would have prevented him joining the ship, or so he reasoned.

And by then he was also discovering some of the advantages of life in the growing Shell oil tanker fleet. “A man can make money here,” he wrote home.

The food and pay were good, he said, and he had a comfy bed and a Chinese “boy” to bring him tea in the mornings and clean his shoes. “It seems to me life is one continuous meal aboard here. In the last ship we used to get one meal a week.”

Monkbarns had been 267 feet long and 23 feet wide, with a very old Old Man, two very young mates, sixteen teenage apprentices and a barely competent crew of a dozen or less, depending on desertions. Shell’s oil-fired steamer Donax by comparison was 348ft long and 47ft wide (… “half the length of Guildford Road, and about as wide…”) with a young master, four ambitious mates, a chief engineer with five junior officers of his own, a Marconi wireless operator, and more than thirty Chinese firemen and crew.

Sea mines still menaced the shipping lanes in 1919. "When they float high out of the water, they are supposed to be 'dead'. Personally I have no desire to poke one of them to see," wrote Bert.

Life on Donax too was a world away from conditions aboard the old windjammer. Third officer Bert Sivell had his own clean, modern quarters with fitted cupboards, a writing desk and and armchair, electric lights and a fan, “and a dozen other things that one would never dream of in sail,” he wrote. The Chinese “boy” woke him at 7.30am each morning with hot buttered toast (“Real butter. Not margarine…”), and polished his boots until they shone like glass. Captain McDermuid was a jolly fellow, only 34 himself, who had welcomed his new juniors aboard with a bottle of wine. And the day the ship took on stores, Bert wrote in wonderment: “More stores have been sent to this vessel for a fortnight’s trip than would have arrived on the last one for a year.”

On top of the good pay, Shell offered a provident fund – 10% of salary, matched by 10% from the company plus a 15% annual bonus; three months holiday on half-pay every three years; and a £3 a month war bonus – because of the many sea mines still adrift undetected in the shipping lanes around Britain.

Above all, prospects for promotion were good. Anglo-Saxon Petroleum was expanding. Rapidly. In 1919 alone the company bought no fewer than 23 ships, to replace the eleven lost during the war. They were a mixed bag of former RN oilers built for the Admiralty and converted dry cargo carriers managed by the wartime Shipping Controller, but the company was agitating for permission from the National Maritime Board to raise its salaries by a further 40% (according to Bert’s new captain) to man them all.

It had been a snap decision to join Shell, but Bert never again left the booming oil giant, nor the girl – my grandmother – whom he had equally hastily met, wooed and won that August.

Read on: The girl next door

Previously: Oil tanker apprentice, 1919