A sailor’s life – 62. New York, New York

America had been “dry” for eighteen months when the Shell oil tanker Pyrula dropped anchor off New York in autumn 1921 under the stern, sober eye of Miss Liberty.

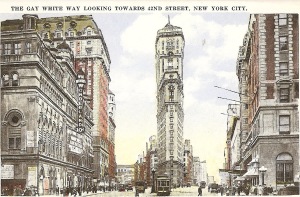

In Times Square legitimate restaurants and bars had closed, and special investigator Izzy “the human chameleon” Einstein and his straight man Moe Smith were already hundreds of arrests into their extravagant career as prohibition agents – sniffing out under the counter liquor in a variety of plausible disguises, from expansive cigar salesmen to thirsty longshoremen.

It was the age of the speakeasy, just “ask for Joe”. There were several thousand underground drinking dens in Manhattan already by that winter, varying from dingy doorways behind which tired bar girls pushed illegally stilled liquor and the lure of sex, to glizy private social clubs peopled by flappers and dapper men in spats. Here, the cocktail grew up, to hide the taste of bad booze. It was the era of jazz, and racketeers and movies.

But the British crew on Pyrula were not destined to see much of the bright lights of the Big Apple. By the time the first snows fell that winter, Bert found himself moored in the open roads off Brooklyn, three miles from the nearest landing stage, as officer-in-charge on a floating fuel pump.

Pyrula was a big ship – 520ft long and “as wide as Union Street,” as Bert wrote to his people back home in Ryde, on the Isle of Wight. She had started life as the White Star steamer Cevic, one of the “cattle boats” carrying livestock and immigrants between the US and Europe. She had been requisitioned by the British Admiralty in 1914 and she saw action as a decoy warship – a dummy Queen Mary, with cylinder tanks built into her holds to carry oil. The Anglo-Saxon Petroleum had bought her after the war and Bert had joined her as Mate in Barcelona in September 1921.

They were bound for New York via Tampico, Mexico, through the hurricane belt. There were 70 officers and crew aboard, all housed over three decks amidships, and his room was the most luxurious he had ever had in all his ten years at sea. It was the size of the sitting rooms in the houses along the street where he had grown up, with electric lights, a fan for hot weather and a bell to the steward’s pantry.

The master was an old sailing ship man who was delighted to discover his new first officer had served his time in sail.

Captain Baxter was nearly 60 and had been 20 years in sail before he and his ship were taken over by Shell. Dolbadarn Castle had been demasted and converted to a motor ship, Dolphin Shell, and Baxter had just returned from three years’ service with her in the Far East. Pyrula was his first steamer.

He knew the ship to which Bert had been apprenticed at 16, and had met the captain, James Donaldson, in ‘Frisco in 1893. Bert for his part had not a bad word to say about the gentlemanly old sea dog — not even when he brought aboard two tiny chinchilla monkeys, which ran amok among Bert’s fresh paintwork with dirty paws.

“Every evening after tea the old man comes up on the bridge and we have a yarn about the old sailing ship days,” he wrote home in his weekly letter to his waiting sweetheart. “He is really very interesting. Some of the places he has taken his ships need considerable skill to get in. He bought a couple of monkeys in Gibraltar. They are the queerest looking things that ever I saw, very lively and climb all over the place. One has a special liking for my shoulder and when walking up and down the bridge this little article will suddenly spring off the top of a door and land on me. They are quite small, not much bigger than a squirrel. I don’t know how they will stand the cold. We have also a couple of cats this trip, stowaways from Gibraltar.”

The orders had been to collect a cargo of oil from Tampico in Mexico and take it to New York, where Shell was keen to grab a slice of the city’s booming 796,000 barrel a year bunkering fuel market. With the US price of oil off the wharf at $1.85 a barrel, the group’s accountants had worked out that they could make over a dollar a barrel profit shipping it up from Mexico, even including freight and handling and the Mexican government’s 14 cents a barrel tax.

For some time, the directors had been casting about for a site in New York harbour to build a shore depot with fuel tanks. In February 1921 proposals were “laid on the boardroom table”, as the company minutes show, to buy and develop a 22 acre site which had been found on the New Jersey waterfront opposite Staten Island. It needed dredging and a pier, and was to have cost an estimated $665,000, but by late summer the scheme had been rejected amid doubts over the vendor’s title to the land and it was decided instead to make do with a cheaper option: an elderly depot ship and a young officer-in-charge.

That August Bert was offered the job – and the prospect of a pay jump from £26 to £35 a month, which was most welcome to an ambitious chap saving up to marry his girl as soon as his first leave was due, in eleven months’ time. He was 26, and had been with Shell for two years.

At home, unemployment was rising. Demand for British coal, steel and woollens slumped after the war. The empire’s markets were in tatters. On both sides of the Atlantic ships were being laid up. Men were being laid off. The old industries struggled, and in the midst of it all a much younger industry, oil, grew strong.

In ten days after leaving Gibraltar they sighted only four ships, even along the US coast. “It shows that the Yankee trade depression is just as heavy as our own because in normal times this coast is alive with shipping, mostly American coastal traffic it is true but even coastal traffic means work for someone,” Bert wrote.

Bert reported 600 vessels idle in Newport News, VA. Worse than any port in England, he said. And New York and Philadelphia were said to be the same.

The men who had deserted the Red Duster for big Yankee wages during the war were on the beach too. “The few American ships running will only carry Americans. None of the crews of British vessels calling here ever desert their ships now, so there is no chance of the stranded ones getting away.”

He had scant sympathy. He had served the war in sail, running saltpetre from Chile for the munitions industry and Jarra wood from Australia for pit props. He had endured low pay, bad food and rough men, but it had taught him his trade and in the summer of 1919 he had been very happy to exchange his crisp new sailing ship master’s “ticket” for a dry berth on oil tankers and three square meals a day.

He was a qualified captain, but it had taken him nine months to climb back to first officer. Officer-in-charge of an oil depot ship was another step up, but it was hard work.

Some weeks Bert was on his feet for 63 hours at a stretch, taking oil from the tankers that ranged alongside them in the deep roads, and discharging it into smaller lighters that tendered among the big ships along the Chelsea piers where the White Star liners and Cunarders docked. Tossed by the backwash of the great Atlantic passenger ships that brought him his mail, far from the bright lights on shore, he watched the immigrants arriving from the old world, huddled at the railings for a glimpse of the new.

There was no telephone aboard. If he needed to talk to the agents he had to take the motor launch ashore and phone from the quay. He visited the office in Manhattan twice a week, taking in lunch at his favourite Chinese restaurant up town. It had an orchestra and dancing, which he watched. He loved jazz and occasionally took in a show or a movie. If he enjoyed other diversions, he did not mention them in the letters and cards he fired off to his fiancee, Ena Whittington, on the Isle of Wight.

Marooned on Pyrula, a mile offshore, with a mainly Irish and Scandinavian skeleton crew of fourteen, prohibition made little impression on Bert, although he was not himself was not averse to a tipple, as he admitted as he nursed himself through the ‘flu that laid waste to New York in January 1922. For several days he had lived on hot malted milk and rum — “shocking, and in a prohibition country too,” – and many a ship master shared a dram of the real McCoy with him after the oil had been pumped across, for it was a cold job.

When a Sinn Fein flag, ensign of the Irish free state, appeared on the bulkhead in the crew quarters he prudently ignored it, but when one of the firemen (stokers) succumbed to what Bert suspected were the effects of “moonshine” he had him packed off to hospital ashore, smartly. The authorities tended to ask unwelcome questions about where booze had come from. But the patient was outraged to discover his pay was stopped while he was laid up and threatened to sue. On discharge he refused to return to the ship, and he died of alcohol poisoning in another hospital two weeks later, one of thousands of victims across the US. (“So that settles his lawsuit,” wrote Bert, unsympathetically.)

Shell tanker Pyrula, master's sitting room, 1922 - time exposure with cat in foreground, probably growling

By the beginning of February the snow was 2ft deep on the deck, and all the pipes were frozen up. As the ice melted, it trickled into his rooms in 26 places. Between ships, the stowaway little black cat that had survived the hurricane was his constant companion. It followed him around the deck like a dog and sat on the safe in his room as he worked, growling at its own reflection in the wardrobe mirror.

Unable to get ashore, Bert’s pay had never quite reached the £35 a month he had been promised; the ASPCo deducted meals at 3s 6d a day for each man. Overtime rates had been abolished the previous October (“though we still have to work overtime, or face the sack…”) and in March, the pay itself was cut by £2 4s a month, the second time in a year. In May it was to go down a third time, they were told, by £1 2s. “We shall soon be going to sea for our health,” he wrote dolefully, but to his surprise only one of his crew quit.

By now, Bert was counting the months until his leave, when he was to go back to the island to get married and set up a home of his own ashore. He had been at sea since he was 15 and never home for more than a few weeks until the summer he’d met Ena.

However, at the end of March, all his plans were thrown into the air. After months at anchor, Pyrula was moved to a permanent berth beside a pier on Staten Island. Pier 14, Clifton, had power lines from the shore and Bert got a telephone in his room. Trains and trams ran past the pier gates straight to the Manhattan ferry and the shows, and in the evenings after work, he was able to take a walk.

By late spring Bert was writing chattily home about the 25 cent movies, the talent nights at the local palais and several sightseeing trips he’d enjoyed in a friend’s automobile.

Life on the pier was a bustle of activity, with “noise and all sorts of things going on” day and night. One week a small steamer turned up and discharged a cargo of cork, lemons, sardines, and almonds into the shed beside the tanker. All day the scent of lemons hung strong about the wharf. Pyrula had just taken on coal, but Bert uncharacteristically left his ship black with dust from stem to stern rather than risk dirty water running off and spoiling the fruit.

Some shore life diversions were less welcome: one night they were burgled, together with the Standard Oil tanker lying beside them, and a four-masted schooner nearby. While Bert slept, the thief or thieves bypassed several night watchmen and the catches on all the doors. “When I woke up at 6am I found my room like a shambles and clothing lying around everywhere.” They had taken his watch, chain and binoculars, plus an overcoat from the steward’s room and shore-going clothes from the other tanker, but missed Pyrula’s pay roll, which was in Bert’s safe, and a gold watch he had brought as a present for Ena.

At home, Ena was busy sewing for the wedding, amid much envy and ribbing from her mates at the milliner’s in Ryde where she now worked. On Pier 14, Pyrula shifted record quantities of bunker oil, the young officer-in-charge was mentioned in letters to head office, and Bert made a momentous decision. His leave was fast approaching. He’d been away three years. He was entitled to go home. But it was rumoured that the agent wanted him to stay.

“If I am ordered to remain here it would be very unwise to kick,” he wrote. “Because I would only prejudice my career in this company.” He would lose Pyrula and his next ship might be out east, where Ena could not follow.

“Come out and marry me,” he telegrammed.

Read on: To have and to hold, Pyrula 1922-1924

Previously: Hurricane at sea

The White Star steamer Cevic disguised as the battleship Queen Mary in 1914, note dummy first and third funnels with no smoke

Mr. Sivell,

I had just asked the National Archives in Chicago if they had a cargo manifest for the Cevic in 1895. They did not, and knew not where to look. I know quite a bit about the Cevic from casual research over a dozen years, but I gave it one last try — a google for ‘Cevic, cattle boat’. And I found A sailor’s life – 62. New York, New York. I’m going to find the start of your book and begin at the beginning.

My interest in the Cevic arose from research I did on a large colony of Irish who settled in Casper and Rawlins, WY. The research became a book and eventually a website, CasperIrish.com. At first there was only Steve’s naturalization record. The date and Cevic led me to the Ellis Island passenger manifest which told me of 5 passengers (only) and 3 stowaways. I knew about all the passengers, but did not pursue Cevic because of more demanding research. Then the archivist at Casper College gave me a manuscript newspaper story about Steve. Steve had been put in charge of 100 blooded rams traveling from England to Wyoming; ah, the Cevic is a cattle boat. A month ago I learned from the granddaughter of the owner of the rams (also aboard), that a boatload of sheep, not just 100 rams — a small load for a ship the size of Cevic — had come from England. Then I realized that the baby boy, of 10 months, was the father of that granddaughter.

I know the names and origins of the stowaways, but nothing beyond.

You can see why I was looking for the cargo manifest.

Harry Ward

Harry Ward

July 20, 2012 at 3:17 pm