Posts Tagged ‘merchant navy’

A sailor’s life – 84. Fake news and an error frozen in time

“In 1906 the sailing ship Monkbarns became trapped in ice while rounding Cape Horn, visible but inaccessible to passing vessels for several months. During this time, her elderly master fell ill and died.”

Down the years, almost every mention of Monkbarns – one of Britain’s last commercial square-rigged ships – has repeated the story. It was a grand yarn, resonant with the hardships and bleak adventure of life at sea in the days of sail. But sadly it simply wasn’t true. It was, as we would say nowadays, “fake news”.

For decades, the story of the old square-rigger helpless in the ice was reproduced in books and newspapers round the world, gathering colour but little detail, reappearing again and again, even as recently as a book published in 2005.

“Re the old Monkbarns,” wrote one old salt to Sea Breezes magazine with conviction in 1927, “this vessel was, in mid-winter of 1906, fast in field ice to the southward of Cape Horn for 63 days, during which time her elderly skipper, Captain Robinson or Robertson (late Reliance), died. We sighted her while in this predicament from the Fingal, when bound from Glasgow to Victoria, BC, Vancouver and Seattle.”

The maritime author Frank C. Bowen of Gravesend, describing the last sailing ships in the Thames in 1930, recounted that when Capt. Charles Robinson took over command of Monkbarns in 1906 “…his first experience of the ship was certainly a wretched one, for she took 203 days to make the passage from Dover to San Francisco, being embayed in an icefield to the south of Cape Horn for no less than 63 days. The experience killed poor Captain Robinson, who was already an elderly man.”

Capt. AG Course, chronicling the lives of Britain’s last windjammers in The Wheel’s Kick and the Wind’s Song, his history of John Stewart & Co in 1951, repeated it. “When outward bound to San Francisco in 1906 she was embayed in field ice to the south-ward of Cape Horn in winter time; bitter Antarctic weather was experienced and she remained hemmed in for 63 days, during which time her Master, Captain Robinson, died.”

Only the Australian sailor and maritime writer Alan Villiers raised a doubt.

“As far as I know, [Monkbarns’] most thrilling adventure in her pre-Stewart days was in 1906, when she was caught in the field-ice south of the Horn and imprisoned there for two months, while outward bound to San Francisco,” he wrote in 1931. “During this period her elderly master died. There must be a story to this adventure, but beyond a few scraps of reference in odd places I have not been able to find it.”

It was a tragic yarn, summing up the impossible harshness of the sea and gales around Cape Horn, and life – and the constant proximity of death – on the last commercial wind ships, which even before the first world war were disappearing from wharves around the world now bustling with grimy steamers and the first internal combustion engines.

To the old boys who had “served their time in sail” to pass the exams that opened up eminent careers in steamship fleets, the tired grey canvas, worn rigging and hard, hungry life aboard the last deepwater wind ships was exciting, part of their youth. Course gathered much of his material in mellow fireside chats with fellow “Mollyhawks” of the Cape Horner’s Association, master mariners who had rounded Cape Horn in tall ships, mostly as apprentices during and after the first world war. They relished their yarns of danger and real deprivation. But 1906 was before their time.

By 1971, Villiers had dispelled the ice story, apparently by the simple expedient of tracking down the log (The War with Cape Horn). However, he added a new twist, questioning the age of the master.

“Monkbarns survived to become one of the last five British deepwater square-riggers, but she was hard on her masters. Among casualties aboard was Charles Robinson, master, aged an official fifty-two, of ‘general breaking-up, heart and lungs’.”

Captain Robinson was a North-countryman, he wrote, who would not have broken up all that easily. “The mate had previously treated him off the Horn for frostbite and failing eyesight. A later diagnosis – still the mate’s – mentions beriberi, severe pains in the legs, tightness in the stomach, etc. Treatment, ‘various embrocations,’ all useless. Apprentices took turns keeping constant watch. The Golden Gate was almost in sight when finally the broken-up old man died, probably of old age.”

Close – but no cigar.

Charles Robinson, briefly master of Monkbarns in 1906, was in fact born in 1852 in Portaferry, Co Down, according to his second and first mate and master’s tickets traced on Ancestry. The backs of the certificates document his sea time in lists of ships and dates. He had been at sea since he was 17.

It would be fair to say Capt. Robinson’s career was not a lucky one. He had been mate of the British ship Impero when it had to be abandoned off Halifax NS in 1880 with a cargo of Indian corn from Philadelphia for Limerick, and was master of the Corsar ship Reliance when she burned out at anchor in Iquique in September 1901 while loading saltpetre. In both cases his certificates of competence were damaged – triggering tell-tale requests for replacements in the maritime record.

When Monkbarns left Hamburg in Germany in February 1906 with an unglamorous cargo of cement bound round the Horn for San Francisco on the US west coast, Capt. Robinson was therefore 54, a relatively modest two years adrift of the age he admitted to. Log entries signed by the mate during the master’s final weeks record that they had experienced cold, damp weather off Cape Horn – no mention of ice – and that the frostbite mentioned was from a previous trip.

What Capt. Robinson did have was a bad heart and a gammy lung, and he had boarded the ship with a warning from his doctor ringing in his ears that “if he wasn’t careful about smoking it would finish him,” the mate noted in the log after his death.

His troubles began within days of leaving Hamburg, as it became evident that the agents had signed on a problem in the galley. By the Bay of Biscay, F. Foezzlonski the ship’s cook had been “logged” for putting sea water in the chicken soup for the cabin crowd aft, and curried porridge was to follow. The words “half crazy” appear in the log as the man’s mental condition deteriorated. Bread was spoiled, the fire was left to go out – unpardonable on an unheated ship fighting through wild, wet storms – and one day the whole pork ration for the officers aft was added to the crew’s dinner. The galley amidships was squalid, the cooking utensils filthy. But Foezzlonski was deaf to both final warnings and reprimands, spending his time in brown study on the galley seat or in fine weather on the fo’c’sle head.

His pay was cut, and cut again, from £4 a month to £2 for “persistent dirtiness”. (And the steward was put in charge of cooking for the cabin.)

Meanwhile, all the usual ship’s business continued. Two men suffered head injuries serious enough to need stitching when the main topsail halyard carried away in the south Atlantic. But the ship was rolling heavily and there was so much water racing up and down the deck that Capt. Robinson didn’t make the attempt. “Bound up the cuts close together and used boracic lint and cold water pads for the night as it was impossible to put stitches in, the way ship was labouring,” he wrote. Twenty-one stitches were applied to the worst injury the following day.

Another man bashed his head and ribs falling 15ft into the lower fore hold, and a fourth twisted his ankle on the heaving deck. Two more had to be treated for clap, “according to directions in the Medical Guide”, and there were septic fingers to poultice and boils to lance.

The log shows Capt. Robinson was still wrestling with Foezzlonski – and the stresses a bad cook generated in a hard worked but now ill-fed crew – until just north of the Falklands. There, on 4 August, a long list of the cook’s misdemeanours was inscribed in the log. Pies and rice puddings burned while Foezzlonski sat on the galley seat, smoking, “with his arms folded”, and when the men growled at him he gave them items belonging to the mates or claimed their rations were poorer quality than the cabin’s. The galley was filthy again.

That was his final entry. Capt. Robinson died a month later on 2 September at Lat 35N/Long 133W, about 400 miles off San Francisco – or as Villiers put it, when “the Golden Gate [strait] was almost in sight”. (The bridge was still 30 years away.)

Dutchman Christiaan Eijkman was awarded a Nobel Prize in 1929 for his contribution to identifying the causes of beriberi.

Kazimierz Funk, the Polish biochemist who in 1912 formulated the concept of vitamins – “vital amines”.

The ship had rounded the Horn with no mention of ice, but full details were logged of the cook wasting water, spoiling food, and stirring up trouble between the officers and the men. “There are the same kind of peas for everyone on board,” A Gough, the mate, put on record on 29 August. The Old Man had started to ail between Cape Horn and the Line, he wrote, complaining of severe pain and swelling in his legs and persistent cold feet. He had self-diagnosed beriberi (caused by a vitamin deficiency not identified for another six years), so the mate treated him for that, “as per Medical Guide”.

The patient was given soap enemas, paraffin embrocations and doses of castor oil, when sadly what was needed was fresh milk, eggs, green vegetables and orange juice. But the voyage had been long and even basics were running out.

Two days before the Old Man’s death, Gough wrote: “Owing to supply of flour running short, shall be compelled to reduce allowance from 2 1/4 lb per week to 1 1/2 lb for all hands.” The difference was to be made up with dried beans. For men with few treats, this meant no bread. A big deal.

Capt. Robinson, master of the Monkbarns, died at 4.30am on Sunday 2nd September and was sewn into a weighted canvas shroud for consignment to the deep. “A sailor’s funeral, with the wide Pacific for his grave,” the San Francisco Call reported, after Monkbarns finally dropped anchor in the US on 12 September. The Los Angeles Herald recorded only that Monkbarns’ master had been buried at sea after long illness, and the voyage had taken 206 days.

Wherever the over-excited tale of the ship’s 63 days trapped in field ice may have come from, it wasn’t the Call’s man at the dockside grilling the hands for this first contemporary account of the voyage:

“The Monkbarns encountered heavy weather in the Bay of Biscay, and from there to Cape Horn her path was beset by gales of more or lass severity. She was sixty days rounding the cape. Hurricane followed hurricane. For two weeks the Monkbarns not only fought gales but dodged icebergs, and when she finally struck the breeze that carried her into the Pacific all hands were pretty well worn out.

In the Pacific the wind treated the Monkbarns with marked discourtesy. Slowly she crept along, her sails now flapping idly and again filling in halfhearted fashion. Near the end of the voyage there was a sudden change. With a roar a northwesterly gale swept the waters and the Monkbarns’ sailors were given another taste of Cape Horn weather. The ship came out of this last gale considerably the worse for wear and until she dropped anchor yesterday the spare time of the crew was occupied in repairing damage.”

OK, so the newspaper’s “sixty days rounding the Cape” may be partly to blame. Misheard? Misprinted?

What became of F. Foezzlonski I also cannot say. Until this coronavirus lockdown ends, I cannot even go back to the National Archives at Kew and lookup up the crew list to find out where he was from, or whether he had ever been to sea before.

Monkbarns left San Francisco on 5 November 1906 with a new cook and a new master, Capt. J. Parry. There would be two more deaths before Monkbarns arrived back Europe and signed off in Antwerp in March 1907. George Anderson, 20, from San Francisco died shortly after Christmas as the result of a head injury, and as they rounded Cape Horn into the new year Auguste Assa, 23, from Luxembourg, was killed in a fall from the topgallant yard. Within two weeks of the ship leaving Antwerp again in June 1907, a 14-year-old apprentice, Joe Ash, was dead, too, of typhoid.

Life at sea was hard enough without needing to embroider anything.

*

Previously: A sailor’s life – 83. Foaming water, clean living

Read from the start:

A sailor’s life – 1. Beginning, middle and end

Written by Jay Sivell

April 28, 2020 at 1:29 pm

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Deaths at sea, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Uncategorized

Tagged with Alan Villiers, Beriberi, Cape Horn, Capt Charles Robinson, Casimir Funk, Christiaan Eijkman, Corsars, death at sea, Fingal (barque), Frank C Bowen, Golden Gate, handelsmarine, Ice, John Stewart & Co, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, marina mercante, marine marchande, merchant navy, Monkbarns, Sailing ship, San Francisco, San Francisco Call, vitamines

A sailor’s life – 83. Foaming water, clean living

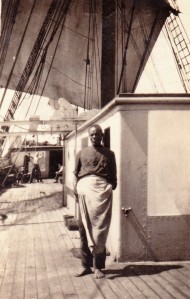

Scantily-clad crew aboard Monkbarns, 1926 – “It then proceeded to rain in torrents and all hands could be seen on deck with next to nothing on, washing clothes. A great day for the sailor’s gear,” Eugene Bainbridge, 6 May (courtesy estate of Eugene Bainbridge)

Descriptions of rounding Cape Horn in sail tend to dwell on ice and howling winds and split fingers and harrowing near-misses. The doldrums, through which ships from Europe must pass to get to the southern hemisphere, feature only as a spot where vessels languish becalmed. The very word has drifted into the English language meaning “inertia, apathy, listlessness, malaise, boredom, tedium or ennui”.

The sheer hard work – and the sailor’s rare luxury of washing himself and his smalls in unlimited fresh water during rain showers in the doldrums – is therefore usually overlooked. This charming reminiscence about life on the German four-masted barque Peking on the Chilean nitrate run in 1928 comes from former Laeisz Flying P-line master Hermann Piening, one of many “grand old boys” interviewed by Alan Villiers, (quoted in The War With Cape Horn):

… And then the trades! That remembered paradise of the ocean sailing-vessel life when all the hardships are forgotten. Through the blue sea the keen cutwater of the sleek, big Peking rips day after beautiful day, scaring the wide-eyed flying fish with the roll of foaming water that forever races at her bow. Here the sailor may feel the essence of harmonious beauty between his ship and the sea. But nothing lasts. The doldrums come with their nervous cat’s-paws of fleeting airs, their sudden swift squalls, their deluge after deluge of almost solid rain.

“You are not to think that we are dealing here with a domain of absolute lack of wind,” says Piening. “That seldom exists, for even slight variations in pressure must always result in movements of air. But the wind is uncertain and faint here. The navigator who is not continually ready to make use of even the lightest breath can spend weeks in this uncomfortable hothouse. There is no rest for the sailors. There are watches in which they hardly get off the braces for ten minutes.

… “There is only one pleasant thing about this region: it rains frequently. In a compact mass, the water falls from the blue-grey sky. Everything and everyone aboard revels in soap and water, for the fresh-water store of a sailer is limited and the duration of the passage most uncertain. A sort of madness seizes everyone. Clad only in a cake of soap, the whole crew leaps around and lets itself be washed clean by the lukewarm ablution. Filled with envy, the helmsman looks at the laughing foam-snowmen into which his comrades have transformed themselves. Everyone pulls out whatever he can wash and lets the sea salt get rinsed out thoroughly. By night the heavy lightning flashes of this region present a splendid show. Often the heavens flame copper-red and sulphur-yellows, and hardly for a second is the vessel surrounded by complete darkness. At times St Elmo’s lights dance upon the yardarms.”

[Editor’s note: The Laeisz four-master Peking is back in Europe after languishing rather unloved in New York for four decades. Yay! A major operation to get her back across the Atlantic in a floating dock last year is now being followed by a major refurb in Wewelsfleth, north of Hamburg.]

Alan Villiers talking to Captain Hermann Piening, ex Laeisz “flying P-line”, from The War with Cape Horn (1971)

Written by Jay Sivell

August 18, 2018 at 2:45 pm

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Other stories, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, Uncategorized

Tagged with Alan Villiers, apprentice, Chilean nitrates, Doldrums, Eugene Bainbridge, F Laeisz, four-masted barque, fresh water at sea, handelsmarine, Hermann Piening, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, marina mercante, marine marchande, merchant navy, Peking, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, seamen's pay & conditions, square rigger, Tall ships, windjammer

Lost at Sea – 82. The sailmaker’s tale

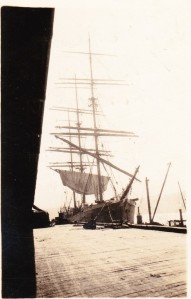

Monkbarns at sea, October 1925 – the Old Man (Captain William Davies), Ian Russell AB at helm and ‘Sails’ Robertson, private collection E. Bainbridge

One of the rare surviving photos of everyday life aboard Monkbarns shows a handsome man in a cap and leather waistcoat sitting on a low bench on the aft deck surrounded by folds and billows of canvas. His tools and twine are laid out in a neat “housewife” beside him, and both hands are busy as “Sails” looks up from his work to smile at the camera.

The master perches on the saloon skylight nearby in jacket and bow tie, having insisted on changing into his good shore-going gear for the occasion. In the background, a youth at the wheel studiously minds the sails overhead. The sea is calm and the sun is high.

Henry Robertson was 70 when the image was recorded in 1925 by the ship’s final English apprentice, Eugene Bainbridge, who brought a fresh eye and a Leica aboard with him.

“Sails” was a grizzled widower from the east coast of Scotland. He liked his own company and staring into the middle distance with his pipe, the master’s son recalled*, and would recite chunks of Sir Walter Scott’s epic poem Marmion to himself whenever he thought no one was listening.

He had been at sea all his life, the son of the court clerk of Montrose who’d died when he was six, leaving the family to experience “what it was like to have the sheriff officer in the house to take away the clock to pay for poor rates,” as he put it.

Back in Scotland were four grownup children, three daughters and a son, born at five year intervals to the pretty housemaid he’d met at a dance in Montrose in his thirties. She had died of tuberculosis in 1907, leaving the baby to be raised by her eldest daughter and younger sister. “Sails” was devoted to them all and wrote frequently to his daughters, but he preferred to stay afloat.

The girls concurred. A studio portrait from 1920 shows a handsome family, happy and relaxed around a proud father. But the girls were resilient and resourceful as well as beautiful; sea voyages were long and mails irregular, and for eight months after their mother’s death they’d forged her signature on their father’s allotment note, to keep receiving Henry’s pay and keep the family together. They also embroidered the truth a little locally, making out that he was a ship’s master rather than a sailmaker, and had run away to sea rather than follow in the footsteps of his stuffy town clerk father and grandfather.

In a letter written the year after his wife died, Henry describes being swept overboard in oilskins and seaboots that March during seven weeks of fearful bad weather south of Cape Horn and only narrowly escaping with his life by hanging onto the line he’d been repairing. “All I thought of when in the sea, ‘my bairns are Motherless now they are to be Fatherless’ – but God has had more for me to do, and saved me from a watery grave for a time.”

Ditton had endured “gale after gale, and the wind like to blow the old ship to pieces,” he wrote to his daughters. “I was in the sea a good while before anyone knew I was overboard, so when they did come to pull me up, I could not hold on so away I went again, I was so numbed with the icy seawater … The skipper says he never pulled so hard in his life as he did getting me on board.” The mountainous seas had also smashed the chart and wheel houses and carried away two of the lifeboats, he said.

Ditton – steel full-rigged ship built in 1891, sailed from Hamburg to Santa Rosalia, on the Pacific coast side of Mexico, in 180 days in 1907

It is an account that seems to offer little reassurance for 18-year-old Nell left caring for her three-year-old brother, but when Henry briefly attempted life ashore, his youngest daughter, Jean, later looked back on it as the worst two years of her life. The girls were used to doing things their own way, and Henry hated living on dry land. So back to sea he went. And at sea he remained.

He and Monkbarns were off Chile when the first world war began far away in Europe, and for five years they were kept busy carrying nitrates for explosives, and flour for troops – dodging enemy raiders and submarines and hunger and mutiny described elsewhere. In 1919, Monkbarns finally struggled home manned largely by apprentices. The old master and the young mate, my grandfather, quit. The “Old Man” – as masters are always called – retired to Australia, and Bert Sivell abandoned sail for oil tankers.

“Sails” hung on, and continued hanging on – patching and mending – as the ship and new young crew spent the next two years trying to beat steamers to peace-time cargoes. When Monkbarns was towed to Belgium in 1921 to be laid up alongside some of the world’s other surplus antiquated tonnage, “Sails” signed on as cook and bottlewasher. The master and mate were obliged to be aboard, but “Sails” was there, the master’s son wrote, “because he had no wish to be anywhere else”.

As the three tugs pushed and pulled them across the Channel in thick fog that September, Henry, leaning on the ship’s rail, puffing on his short black pipe as was his habit, will have passed the remains of HMS Vindictive still visible off the mole at Zeebrugge, and the deserted tangles of barbed wire in the sand dunes along the coast. Inland lay a lunar landscape of dead tree stumps, shell holes and trenches.

Monkbarns came to rest in Bruges, seven miles from the sea, beside a row of concrete U-boat pens in an outer dock a mile’s walk and a tram ride from the great medieval cathedral and picturesque canals. Beside and behind her were three other laid-up ships, including Laeisz’s Perim and H. Hackfeld, confiscated from the Germans by the Allies as war reparations to the Italians. The ink was barely dry on the treaty of Versailles, ending the first world war, and around them Belgium was a wasteland.

Pretty Bruges itself, however, had survived the war largely unscathed as an enemy-occupied marine base, where German frontline troops came for brief R&R from the mud and blood of Ypres and Passchendaele, billeted on local families or in schools and churches. Officers of the Kaiser’s army came from miles around asking to see the town’s collection of Flemish Primitive paintings. The main damage was “friendly fire” from Allied attacks, parried by the new German Flugabwehrkanonen (Flak).

By Christmas 1921, there were lights and decorations, bright shops spilling light and warmth onto the cobbles, and fantastic chocolate confectionary too amazing to eat, according to Captain William Davies’ son, Ifor, who had arrived for the school holidays in the station cabbie’s horse-drawn landau. His mother and younger brother were already living aboard.

Ifor remembered fondly the warm welcome the Welsh family received from their “well-fed” Flemish butcher and his wife and daughter in the Grand’rue and the genteel patissier where they bought their bread, cakes and groceries. Mijnheer Lobrecht produced cigars for Captain Davies and thick slabs of chocolate for the children, while Monsieur Fasnacht – “a tall slender gracious old man with a sparse imperial beard and gold-rimmed spectacles” – conjured up steaming cups of hot chocolate.

At the moorings, too, a small convivial international community had formed, with lots of visiting. Captains Graziano, da Costa and Mazzoni poured mysterious drinks in tiny glasses and their wives introduced the family from Nefyn to ravioli. Communication was fractured, but no one minded.

During the summer, Sails could watch from the rail as the children played football on the concrete floor of the old German barracks, or rowed on the canal. Sometimes they took a trip on one of the barges plying the waterway to the sea, or helped local farmers picking fruit – returning with bags of fresh produce. In winter the dock froze, and they played on the ice around the ships until Mrs Davies called them in to eat. If the weather was bad, they hung around the warm galley, watching the old Scot prepare their meals, or huddled in the sail locker to watch him pushing the big needle to and fro through the mountains of canvas with his leather sail-maker’s palm.

Laid-up or not, the work of mending the standing rigging and patching and “roping” the sails – sewing on hemp bolt-rope edges for strength and identification – continued.

Arbroath on the east coast of Scotland, immortalised by Sir Walter Scott in The Antiquary as “Fairport” (Private postcard)

Monkbarns spent 16 months in Belgium but Henry was only lured ashore once, on Christmas Eve, and then only came out of courtesey to Mrs Davies because, as her son put it, “he was a gentleman”. Mostly he kept himself to himself, refusing invitations to join the family in the saloon and settling instead in the warmth by the galley stove with his pipe. He was a keen reader with a rich booming voice, and loved to recite to himself for hours on end. He knew by heart enormous stretches of narrative poems like Marmion and The Lady of the Lake (“Where shall he find, in foreign land, so lone a lake, so sweet a strand…”)

“Most of the time, we respected his privacy,” Ifor recalled. “But once in a while Dick [the mate] would tempt us after supper to leave the saloon and tiptoe towards the galley so that we could hear Sails. If we knocked at the door he would courteously invite us in, tell us to make ourselves at home, and then, without a trace of self-consciousness or condescension, continue where he had left off.”

To Henry, the works of Sir Walter Scott were not merely pleasant recreation but also a link with home. Monkbarns is the main character in Scott’s third Waverley novel, The Antiquary; a well-to-do collector living in an ancient house Scott based on Hospitalfield, Arbroath, the leprosy hospice founded in the 13th century by the monks of Arbroath abbey. Scott had stayed there as a guest. When Sails signed on with Monkbarns he gave his address as 24 Allan Street, Arbroath.

The ship Monkbarns was one of three commissioned for a prominent local canvas manufacturer. He named them Monkbarns, Fairport (as Scott called Arbroath in the novel) and Musselcrag – the abbey’s old fishing village, Auchmithie.

Steam-powered shipping was already cutting the demand for sailcloth by 1895, when Monkbarns was launched, but there was still a living to be made in sail, where the wind was free and labour cheap, and Arbroath was a mass of saw-tooth factory roofs and chimneys to prove it.

Charles Webster Corsar could have invested in steamers to bring in the Russian flax his factories needed, but the last surviving son of the weaver with the vision to buy James Watt’s engine chose instead to build sailing ships, and with a wry flourish he named them after a historical romance.

Newspaper cutting from 1925 with Monkbarns ‘old-timers’ Sails Robertson and the ship’s cook, Josiah Arthur

A newspaper cutting from 1925 again shows Henry Robertson sitting on Monkbarns’ deck surrounded by canvas, now with the ship’s black cook, Josiah Arthur, posed beside him. The journalist describes them as “the knight of the needle and the cracker-hash king … survivors of types the world will soon know only in history”. There was hardly a square foot of Monkbarns’ canvas that had missed Henry’s palm and needles in 14 years, he wrote, and Arthur claimed to have cooked more cracker-hash, dandy-funk, and lob-scouse than any ship’s cook left in active service.

‘“No steam-boats for me, massa,” said Josh of Jamaicy,’ runs the toe-curling prose. ‘“I’ve always been used to serving out lime-juice and trimming salt-junk, and at my time ob life, massa, I don’t feel like turning on ham and eggs and peaches and cream for steam-boat sailors.”’

The crew list for that voyage reveals Josiah was in fact from from Barbados not “Jamaicy”, and that Henry had sheared ten years off his age. He still looked good. He could get away with 60.

Four years later, however, the old Scot was dead. Captain Davies, too, was dead, probably of stomach cancer. He fell ill on what was to be Monkbarns’ final rounding of the Horn and was buried in Rio. Monkbarns herself had limped back to the UK only to be sold for a coal hulk. The boy with the camera failed his sight test and never sailed again.

Monkbarns sailmaker Henry Robertson and his leather sailmaker’s “palm”, in the Signal Tower Museum, Arbroath

After a lifetime at sea, Henry Robertson finally went home to his children and grandchildren, and he lies buried with his Kate in Sleepyhillock cemetery, Montrose.

His sailmaker’s palm, a last tangible link with the ship, sits on a glass shelf in the Signal Tower museum in Arbroath – beside one last view of Henry surrounded by billows of canvas, stitching in eternal sunshine aboard Monkbarns.

*J Ifor Davies, Growing Up Among Sailors, 1983

Written by Jay Sivell

July 29, 2018 at 12:15 pm

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Other stories, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship mutiny, Seafarers' wives, Uncategorized, WWI

Tagged with Arbroath, Bruges, Corsars, Ditton, handelsmarine, Henry Robertson, Hospitalfield House, John Stewart & Co, Josiah Arthur, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, marina mercante, marine marchande, merchant navy, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailmaker, sailmaker's palm, Sailors wives, Signal Tower museum, Sir Walter Scott, square rigger, Tall ships, The Antiquary, U-boat pens Bruges, war at sea, windjammer

Lost at Sea – 81. Monkbarns, lingering traces

Monkbarns – and Corsar’s little white flying horse – “taken from the bowsprit end, plunging her nose in a foaming billow,” as the Sydney Morning Post correspondent put it. Photo E. Bainbridge estate

A colour piece in an Australian newspaper reflects the end of days for sailing ships like Monkbarns. While the writer “Sierra” was sauntering among the old-town dockside pawnbrokers and marine artists’ shops in Sydney as the Twenties roared around them, Monkbarns was being towed to Corcubion with her final cargo – to serve out her twilight in northern Spain as a coaling hulk for Norwegian whalers. Astonishingly, she remained afloat until the late 1960s.

“…Here are ship-chandlers, seamen’s fitters, sail makers, fried fish shops, and Chinese laundries, pawnbrokers’ and curio shops packed with treasures from foreign lands, and nautical instrument makers … A peep at the curio shops sends the mind foaming in strange places. Chinese gods and ivory pagodas, chopsticks, Polynesian canoes, Burmese tatooing instruments, sea shells from every strand, guanaco skins from Patagonia, Esquimaux fish hooks and Zulu knobkerrles guide the roving fancy through mysterious lands.

Pawnbrokers’ windows bear witness to the pride once taken by seafarers in the art of sailoring. Stowed away here are the relics of a vanished race; their prized marlin spikes, their fids, prickers, sewing palms, and their Green River knives. Here, too, are their concertinas, sou’westers, badge caps; oilskins that seem to have caught and held a watery gleam of Cape Horn sunshine; a pair of evil-looking knuckle dusters, perhaps the last marketable possession of some stranded bucko mate; a rust-bitten cutlass, and ancient sea boots with desiccated dubbin still adhering in the cracks, reminiscent of the days when sailors really paddled about in salt water.

But the most fascinating shop of all is that of the marine artist. Tea clippers, wool ships, brigs and schooners, under flying kites or stripped for storms, are depicted cleaving the seven seas. Some, framed in miniature ships’ wheels and lifebuoys, are seen bounding along under the bluest of skies, their gaudy colours streaming from peak and masthead in greeting to distant promontories.

All the old-timers are here. The Great Britain in her glory of full canvas, and, in her decrepitude, a hulk at Falkland Island; the Cutty Sark running before a rousing gale; green Thermopylae racing up Channel under a cloud of stunsails; the stately Macquarie placidly gliding over smooth water; and the Loch Katrine, dismasted in a hurricane, her mainmast gone by the board, and her fore topmast diving into a turbulent sea.

schooner deckloaded to the shearpoles waddles behind a squat tug; the barque Vincennes Iies wrecked on Manly Beach; and a superb clipper rounds to and drops anchor, her sails thrashing in the wind so naturally that the thunder of her canvas seems to reach the ear.

But it is only the rumbling of a six-horse lorry passing along this enchanting street.”

Written by Jay Sivell

July 16, 2018 at 5:20 pm

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Historical postcards, Other stories, Uncategorized

Tagged with Bert Sivell, Circular Quay, Cutty Sark, handelsmarine, Illawarra, John Stewart & Co, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, Loch Katrine, Macquarie, marina mercante, marine marchande, merchant navy, Monkbarns, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, square rigger, SS Great Britain, Sydney. NSW, Tall ships, Thermopylae, Vincennes, windjammer

A sailor’s life – 80. Worse things happen at sea: the steward’s story

Monkbarns unloading nitrates in Walsh Bay No 10 Sydney, May 1925 (Copyright estate of Eugene Bainbridge)

David Morris called himself a journalist, a writer. He’d been on the lookout for a job on a square rigger for months before he heard of Monkbarns in Sydney in June 1925. He wanted “atmosphere” for some historical sea stories he was preparing to publish, he told the Newcastle Sun as the ship loaded Australian coal for South America. He wanted thrills, he wanted to “see the Pacific at its worst”.

Around him on deck, eyes slid away. “Some of the crew, with that superstition born in seamen, are inclined to regard him us a hoodoo,” the reporter noted.

Three weeks earlier Morris had shot across to Walsh Bay, Sydney, where the ship was discharging nitrate, and buttonholed the mate, offering himself in any capacity at a nominal wage. The mate had said “Nothing doing”, but as he trudged off down the gangway, they’d had a rethink. If he really wanted the experience, said the master, he could come along as a general helper at £2 a month (about £1,000 per annum today.)

Was it a cheap shot they’d expected him to refuse? Morris called himself the Captain’s steward, though he appears on the crew list as Cabin Boy, but pay for a seaman was £10 a month, not £2. Then again, as steward or “boy” he didn’t have to go aloft in all weathers or stand his trick at the wheel. He was a housekeeper, minding stores and dispensing first aid.

“Yesterday Morris was caught sewing his shirt, with stitches that would disgust a housewife, on the steps leading to the poop deck. He is a well-built man of 25, but he looks more like 30. The small moustache on his upper lip, and the tan shoes and the tweed suit already soiled by work in the galley, looked strangely out of place there,” said page 6 of the Newcastle Sun.

Movie poster for The Ship from Shanghai released in 1930 (http://adventures-of-the-blackgang.tumblr.com/

London-born Morris had visited most ports in the world as a passenger, and had slept in some of Australia’s best hotels and its least inviting parks in his quest for “atmosphere”, readers learned. He had been inspired to join Monkbarns by the runaway success of a sea thriller published the previous year by another young Australian journalist, Dale Collins. Ordeal is based on a round-the-world trip Collins made aboard the motor yacht Speejacks as historian to the US cement magnate Albert Younglove Gowen, who happened to be on his (second) honeymoon. The novel – about seamen turning on their idle rich passengers – was filmed in 1930 as The Ship from Shanghai, with Louis Wolheim as the ship’s crazed steward who holds them all hostage.

Morris was quite frank about what he was up to; there were men on Monkbarns who had had remarkable experiences, he told the newspaper, and he wanted to “chase up” some of those real-life stories. But he seems to have fallen short on listening. This may have been a world of horny-handed hard cases risking life and limb in all weathers aloft, but they still wouldn’t set sail on a Friday, or whistle for fear of challenging the wind, or even say “pig” out loud.

Of the 28 men and boys who had left Liverpool in March 1923, one was dead – a 19-year-old apprentice lost lashing down an escaping sail during a hurricane – two had been left behind in hospital injured, and two more would die before they dropped anchor back in the Thames in 1926.

Monkbarns 1923 securing lifeboats under heavy seas off the cape (probably photographed by 3rd mate Malcolm Bruce Glasier)

By June 1925, only the captain, the mate, “Sails”, a couple of ABs and the older apprentices remained of the original company. It was they who had faced down disaster on the passage out, when a hurricane south-west of Good Hope knocked them so badly that the cargo shifted. With the lee side of the ship 12ft under and green seas raking the deck, it was they who had risked their lives deep in the hold, shovelling rock salt uphill for three days to try to right her. Young Cyril Sebun was lost off the upper topgallant yardarm while they laboured. But nothing could have been done to save him. The boats were all smashed.

Eventually, they put into Cape Town in distress – a first for Captain William Davies. “During my forty years of service in sailing ships I have never had an experience that can in any way compare with this recent one, and to be quite frank, I should not like to pass through a similar ordeal again.”

On arrival in Australia, three seamen deserted – abandoning their pay – and Morris’s predecessor killed himself with an overdose of chloroform. He had been drinking heavily, the inquest noted. He was buried in Stockton NSW, where some of his former shipmates from the SS Argyllshire called the following spring. They sang Welsh hymns at his grave, and laid artificial flowers. They knew.

So, it was not surprising that Morris’ taste for ill winds made his shipmates uncomfortable and by the time Monkbarns had been at sea for two months, things had turned nasty.

Three entries from the diary kept by one of the apprentices, Eugene Bainbridge, offer a snapshot: 23.8.25. Sunday. Played Bridge all day and was 600 up to finish. It has been quite parky lately and it was anything but warm at the wheel from 12-2 tonight. Course ENE, on starboard tack. Shaved David Morris’s beard in half deck after putting him forcibly on the floor. He seemed a bit peevish and didn’t play ‘Vingt et un’ very well afterwards. The job we made of his beard wasn’t very good.

24.8.25. Monday. Clear, calm, sunny, fresh. Doing about 2-3 knots. Course ENE. ‘Maurice’ came in for about two minutes tonight. He seemed to know that there was something in the air and beat it.

The Pelican Society photographed by Eugene Bainbridge – Newcastle-Callao 1925 (Copyright estate of Eugene Bainbridge)

25.8.25. Tuesday. A night of revelry of a peculiar sort. The subject was ‘Maurice Moscovich’. Notices were posted on the half deck doors inviting you to a singsong to be held in the fo’c’sle at 6.30pm. The Mate was particularly asked to refrain from blowing 2 whistles and when told why, was quite sympathetic. At 6.30 sharp, we met and the subject [Morris] had wandered into the gay party.

It was a bluff. He was to be seized in the middle of its proceedings and tried by the chief Pelican and his confederates. All passed off as planned and the victim was found guilty of not supplying the fo’c’sle with molasses and duly sentenced to have his port beard and starboard ‘tache shaved off. Cold water was used to emphasise the gravity of the act, and Bill Hughes, the Court Hairdresser, operated.

But worse was to come, because Morris evidently put up resistance to the assault, verbally if not physically. Bainbridge, a 21-year-old ex-boarding school boy from Maida Vale, London, records that the victim was deemed to have been “unduly insolent” to his tormentors – and a vote for death by dropping over the after part of the poop was passed.

Maurice Moscovitch as Shylock at the Royal Court, London, 1919 (From: http://exhibitions.europeana.eu/exhibits/show/yiddish-theatre-es/jml-las-obras/item/130)

It is possible that there was more than a little anti-Semitism in this “hazing” as Maurice Moscovitch was a well known Russian Jewish stage actor that summer wowing Australian audiences with his Merchant of Venice and Morris’s middle name was inscribed on the crew list as Isidor. Bainbridge had been to see Moscovitch at the Criterion theatre while Monkbarns was in Sydney.

More worrying still, the punishment meted out – for poor stewardship of the few treats that made the ship’s diet of salt meat and pulses bearable – apparently had the backing of the Master and the Mate. Bainbridge writes: We next trussed him up in a sack etc and took him aft for the mate’s inspection.

The procession marched solemnly back singing ‘For it’s a Lie’. Prisoner was next trussed up again (more securely) and taken forth to his execution. Maurice was marched up on to the fo’c’sle head and lowered away over the break. The wash tub was underneath and someone was making a noise like water. The stunt worked so far and when about a foot off the deck, the word was given and Maurice was dropped!!! He arrived in a heap at the side of the ‘donkey’ [steam winch] amid cheers and benedictions from the High Priest.

Had Morris believed his hostile playmates were actually dropping him gagged and bound into the Pacific? It seems more than possible, but he showed his mettle by joining them in the fo’c’sle, where proceedings continued as a “sing song”, and reciting a chunk of Kipling for the company. Whereupon everyone joined in a hearty chorus of “For he’s a jolly good fellow” and peace descended. Bainbridge wrote: The Old Man and Mate were both observed to be enjoying it uncommonly.

Many years later, “Bill the Court Hairdresser” – by then Captain William Hughes, sir – remembered David Morriss [sic] and his quest for atmosphere. “He got it all right, and I’m sure that what he went through before reaching London would fill two or three books,” he told AG Course, chronicling the history of the John Stewart ships for his book The Wheel’s Kick and The Wind’s Song.

View of Valparaiso harbour with Monkbarns marked by apprentice Eugene Bainbridge with an arrow at the bottom (copyright estate of Eugene Bainbridge)

Two months later, just outside Valparaiso, he was still annoying the apprentices (Dave joins us, and we are bored to a standstill with his platitudes!) but he’d graduated from ‘Maurice’ to Dave. And in port, Dave showed a pleasing openhandedness with the ship’s stores as the apprentices rowed around visiting and being visited by boys from neighbouring ships. (Dave got us some stores and there was plenty of scoff. He unfortunately spoilt this good turn by telling some of his tall yarns.)

However, as soon they put out to sea again and rationing restarted, the moans resume. 9.3.26. Dave wants to substitute sugar for molasses instead of substituting jam. This is not a fair exchange as sugar doesn’t go well with bread and butter! 5.5.26. Dave has been making mistakes with the weighing out of the butter and the tins containing so painfully small a quantity we complained and found we were getting less than our whack!

Happily, nine months after Morris’s sentencing by the Pelican Club, the horseplay had become rather more inclusive, if no less rough. By then, Captain William Davies was dead in Rio de Janeiro, the Mate was the new Old Man and the ceremony as Monkbarns passed Lat 0° 00’ 00” was a more or less welcome letting off steam after a very trying few months fighting their way round the Horn with the dying man refusing to put into port.

Young Bainbridge had a ringside seat. 9.5.26. Sunday. Crossed the Line last night. We all ‘felt the bump and noticed that the ship was going faster downhill!!’ At 1.30, I was let into the secret by Bill that we ‘offenders’ had to ‘go through it’. The Old Man had made some pills of ginger, glycerine and several other ingredients and covered them with sugar (of which there is a very large quantity aboard from Rio.) Jim had made some very ‘choice’ mixture of tar, tallow, soap, Melado (molasses) and red lead.

Monkbarns, Neptune’s court May 1926 – crossing the Line. Neptune and wife right, Dave Morris and Eugene Bainbridge among the tarred six on the left (copyright estate of Eugene Bainbridge)

In time honoured tradition, Neptune appeared over the side clad in oakum and bearing a huge trident made from the mast of the for’rard boat, accompanied by his Wife, his Barber, his Parson – in a lead foil cassock and paper collar – and his Doctor carrying the bag of pills. They set up court on the main hatch.

Bainbridge and Morris were among six “first trippers” the god of the sea wanted to inspect for fitness.

I was first blindfolded and then marched to the main hatch, falling over several ‘lines’ drawn across the deck. We had made the washhouse door fast and they had to break the handle off to get in. I was first asked by Neptune why I had done this and if I had crossed the Line before and why I hadn’t been ‘put through it’!

I then kissed his wife’s foot, which was covered with tar and was then shaved using the mixture, getting plenty of it in the mouth. I received the pills and spat them out. At a second shot, I managed to conceal one behind my tongue but before I could remove it my mouth was sore! I finished up being tipped backwards into a tub of water and then liberated. After I had seen two or three others done I went onto the boom and caught a 24lb bonito, which we had for tea. The proceedings broke up with all hands ‘splicing the main brace’.

They were back in the northern hemisphere after three years away, and “home” suddenly seemed closer. But Monkbarns’ adventures were not over. Progress was slow. Supplies ran out. By 450 miles off the Lizard they were down to rice and ersatz bread, but once into the shipping lanes an obliging German steamer provided relief.

They brought the boat alongside and the provisions pulled aboard: three sides of bacon, two hams, two cases of spuds, three sacks of flour and about 16 tins of Argentine boiled beef (we had some for tea and it was excellent), a certain amount of margarine and butter for the cabin, also lard and Dutch evaporated milk. Then the Cook gave us curry and rice for breakfast!!!!!!!! It was nearly the last of him.

But two weeks later they were still 12 miles off Portland Bill, and “reduced to rice, tea and a little jam and bread”, according to another unpublished diary of that voyage, by able seaman Dudley Turner. “Not had a smoke for weeks, which makes matters a lot worse.” And the Old Man was refusing to flag down any more ships.

When they picked up the pilot off Dungeness and it was discovered he handed out cigarettes for good steering – the first tobacco seen aboard for weeks – there was a rush to relieve the wheel frequently. “Never had such good steering been seen before by the old ship,” wrote Course. But they were so undernourished that the tug crew had to help them haul the hawser aboard.

At 6pm on 10 July 1926, Monkbarns dropped anchor off Tilbury. The pilot presented them with a sack of potatoes and Bainbridge records a “memorable feed of sausages and boiled spuds!!! Never was a meal so appreciated”.

The following day they were towed up to Charlton Buoys, a vessel from a bygone age gathering crowds on the banks, and there the crew were paid off.

And there the story ends. Monkbarns was sold “foreign”, and towed to Corcubion in northern Spain to end her days as a coal hulk. Eugene Bainbridge abandoned the apprenticeship for which his father had shelled out £42 and never went to sea again. What became of David Morris I cannot tell. Bill Hughes thought he’d gone in to radio in Melbourne. If he ever wrote up his historical sea stories, neither AG Course nor I could find a trace.

Bizarrely, the real thrill-seeker aboard Monkbarns that trip turned out to be the youngest apprentice, 17-year-old Len Marsland of Brisbane. After rounding the Horn in sail, in 1929 he pops up as a member of Sir Douglas Mawson’s Australian Antarctic expedition. He worked as a prison guard in Canada, chased the explorer Sir Hubert Wilkins across the Atlantic in an attempt to sign up for his submarine expedition under the polar ice, reappeared in Reykjavik, erecting a signal station, and then back at sea as an officer on an icebound freighter in the Baltic and facing down machineguns in a Russian Black Sea port. Tragically, Marsland’s adventurous career was short. While working as a stuntman for Sir Alan Cobham’s famous flying circus in 1935 his parachute failed to open. He fell 1,000 feet and died in Esher, Surrey, aged just 27.

Previously: A doctor aboard 1913

Written by Jay Sivell

May 29, 2016 at 12:39 pm

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Other stories, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, Uncategorized

Tagged with AG Course, apprentice, cabin boy, Captain Bill Hughes, Captain William Davies, Cyril Sebun, Dale Collins, David Isidor Morris, discipline and desertions, Eugene Bainbridge, first tripper, Frederick Leonard Marsland, handelsmarine, John Roberts, John Stewart & Co, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, marina mercante, marine marchande, Maurice Moscovitch, merchant navy, Newcastle NSW, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, seamen's pay & conditions, ship's steward, square rigger, SS Argyllshire, Tall ships, The Ship from Shanghai, Valparaiso, Walsh Bay Sydney, windjammer

A Sailor’s Life – 79. Doctor aboard (1913)

Tramping round the capstan, Monkbarns, by apprentice Eugene Bainbridge, 1924-26 (copyright: Estate of Eugene Bainbridge)

Much of what we know about the dying days of sail was recorded after the First World War, when most of Britain’s last old sailers had been sunk or ‘sold foreign‘.

Eric Newby’s The Last Grain Race and Elis Karlsson’s excellent Pully-haul were published as late as the 1950s and ‘60s, both about what were by then Finnish-owned vessels – the Moshulu, now a restaurant (!) in Philadelphia, and the Herzogin Cecilie, a wreck off Salcombe, Devon.

But in the summer of 1913, when the Liverpool-registered square rigger Monkbarns arrived off Australia from South America with a state-of-the-art Cinematograph movie camera provided by the Kineto film company of Wardour Street, London, “Everything that could be filmed about life aboard had been filmed,” the resident amateur cameraman noted.

Dr Dudley Stone was a keen yachtsman and junior doctor at St Bart’s hospital London who had joined Monkbarns in Gravesend that February determined to chronicle what was even then obviously the end of an era, from “swinging the ship” for correcting the compass before they sailed to the shanties round the capstan as they weighed anchor. His commission was to “obtain pictures of the ocean in its angry moods”. It was Kineto’s second attempt, after the chap it sent out the previous year had found himself vilely incapacitated by seasickness.

Over the months that followed, as Monkbarns crossed the Atlantic to Buenos Aires with a cargo of cement and then headed back eastwards in ballast round the Cape of Good Hope to Sydney, he shot 9,000 feet of film: of the men hauling and chipping, of the view from the yards, of big seas and the master in his oilskins. He developed it in his cabin and dried it all in strips festooned around a lazarette under the fo’c’sle head.

“I have cinematographed with no gloves and with oilskins and top boots on from aloft from almost everywhere.” Dating and developing it all had taken up to five hours a day, he wrote from Newcastle NSW.

Sadly, this nearly two miles of film seems to have disappeared. It is mentioned in the Australian newspapers of the time and was picked up years later by Captain “Algie” Course during the fireside yarns with fellow Cape Horners that formed the basis of his account of Monkbarns in The Wheel’s Kick and The Wind’s Song, but of the actual film there is no trace, not in the National Maritime Museum collection, nor the British Film Institute, nor the Australian Maritime Museum in Sydney. Shot from a heaving deck over 100 years ago, washed in saltwater, dried in a dusty locker and exposed to sulphur fumes when the ship was fumigated in Newcastle, it is unlikely any of it has survived.

Dr Stone’s unfinished diary, however, did survive – in the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich – and even without moving images it provides a rare glimpse of working life aboard one of the last British full-rigged ships a full 16 years before Alan Villiers and his ill-fated colleague Ronald Walker immortalised Grace Harwar, the last full rigger in the Australian trade.

Stone and his friend and patient, the Honourable John Gilbert Eveleigh-de Moleyns, aged 34, fifth son of the 4th Baron Ventry, were an odd couple aboard a working ship; de M’s condition is not identified but he lay down every afternoon, and usually played Euchre with the Mate for matches in the evenings or made quoits, which he played on deck when the weather permitted. Meanwhile, Stone was out along the yards or down the holds in all weathers with his Cinematograph, filming, or learning to take a noon sight and wrestling with calculations of the ship’s position and progress.

Neither did any actual work aboard, apart from “tailing on” occasionally.

But they roamed at will armed with a Videx Reflex and a Brownie, and Stone’s eye was keen. He noted the pilfering of stores by the ever-hungry apprentices, rough justice for a suspected thief who was given a hiding by his shipmates and booted ashore in Buenos Aires, and the stowaway “discovered” drinking tea in the fo’c’sle after they sailed. The Mate hadn’t known he was aboard, but the master did. Desertions had left him shorthanded. Two “stowaways” appeared after the ship had sailed, and both were entered on the articles at £1 per month.

Patrick Haggerty was an Irishman from Queenstown, Cork, red haired, blue eyed and popular. A fine shantyman, said Stone. He claimed to be off an Italian barque that had gone ashore near Buenos Aires and had only the dungarees, socks, cap and shoes he stood up in. After he was found half frozen at the wheel one night, the ship had a whip-round for him: the Mate gave him a shirt and an old oilskin, de M donated pants and socks, Stone rooted out an ancient spare jersey.

Stone’s surviving diary begins as they leave Buenos Aires.

A doctor was a familiar sight on passenger steamers, schmoozing the saloon crowd and keeping at bay any unpleasantness from steerage. Naval vessels too usually had a surgeon, to patch up battle injuries. But merchant ships knocking about the world with cargoes of nitrate or guano rarely enjoyed the luxury of trained medical assistance.

In the days of sail, physicking the crew was the responsibility of the “Old Man”, supported by a dog-eared copy of the Ship Captain’s Medical Guide and a case of pre-mixed bottles and papers labelled Solution No. 5 and Powder No. 3. Far from land, way off the steamer tracks and with no wireless to call for help or seek advice, the master had to rely on common sense and caution. Any ailment that didn’t involve actual blood loss was potentially malingering, and logs show intervention was rarely rushed. It is hardly surprising then that the presence of a bona fide doctor aboard Monkbarns was greeted with enthusiasm by her crew.

They set off from BA with all seven apprentices and three of the fo’c’sle down with diarrhoea, due to “the change of water”, the master diagnosed, and throughout what was to prove a very rough passage Dr Stone was kept busy.

Within a week storms were raking the ship. It was hard to sleep, wrote Stone. The main royal broke loose and tore both sheets out. The foresail ripped the starboard reefing jackstay clean off the yard, and the fore topmast staysail chafed most of the way through its bolt rope. In the store room all the pickles and a case of kerosene were lost. The following morning Stone watched the steward and two of the apprentices leaping about among the stores trying to catch tumbling tins. “Some had burst (I only hope they are the ‘blown’ ones I saw and that we will be saved from Ptomaine poisoning)”.

The fore hold was a jumble. There was rope everywhere, hanging over the edge of the ‘tween decks and tumbled below. The ship had acquired a list to starboard, and was rolling badly. The skipper had told him the squalls had been hurricane force 11 to 12, and that they might not have survived the night if the ship had been loaded. The boys’ half-deck had flooded.

Stone, who did not have to get up in the night to clamber aloft replacing blown-out sails, or sleep on a wet bunk in wet clothes, was amused to note that all the master’s drawers had shot out and his rug had spontaneously rolled itself up, but he was less pleased that the loss of the oil meant lights out at 9pm. There were only four candles aboard (his and de M.’s) and the ship was “badly found for matches”.

As paying passengers Stone and de M. occupied separate cabins in the saloon aft, with a porthole and two bunks each for all their gear. This left Leslie Beaver, the out-of-time apprentice acting 3rd mate, relegated to the lower bunk in the 2nd mate’s cabin.

“The Mate’s and 2nd mate’s cabins were like store rooms for nick-nacks and old rubbish. Their doors being opposite each other the contents of both cabins were well mixed. I just missed being hit by a camp stool paying a flying visit from 1st to 2nd’s quarters. Beaver had the much used water in their basin, the contents of a water jug and a tin of Swizo milk spilt into his bunk. He borrowed rug etc from de M. for night ”

More seriously, one of the ABs was injured. “Whole gale, hurricane squalls. Tremendous big NW Sea,” recorded the mate. “W Chapman knocked down and hurt.”

On June 7, Stone saw six “patients”, including Chapman, whose leg was skinned from knee to ankle. My own grandfather, then an apprentice of 18, sidled into the narrative with a tap at the doctor’s cabin door that evening. Stone noted an inflamed ligament, painful to the touch and prescribed iodine.

Captain James Donaldson was not pleased, though whether it was the molly-coddling or the lèse majesté is unclear. On June 11, Stone noted: “9.30 Went the rounds of the fo’c’sle at skipper’s invitation – a gentle hint that he does not like my going there on my own.”

Chapman’s raw leg was much better, a swollen knee was down and young Sivell was back at work again, against medical advice – (fed up with doing nothing, noted Stone.) Meanwhile, there was a strained shoulder to inspect (“nil to be seen. I’m safe…”), and the 3rd Mate had been shot into the scuppers on his stomach during a particularly heavy roll, resulting in appalling bruises but fortunately no internal injuries.

And still the glass continued to fall, down to 28.58. The fore lower topsail carried away.

At 3.30am, on a page labelled Hurricane, Stone recorded: “Broached to on port tack – my top row of bookshelf showered its contents on my head and then continued across cabin. Got up and collected them. 4 Very heavy squall carried away fore topmast staysails and new No 1 canvas sail. 7 de M came over to me and I produced LGCL book on meteorology and we tried to make out what position we were in with not much success. 7.30 Hot coffee went the rounds. 8 Broached to on port – more things going to leeward – thank goodness the ballast remains a fixture. This is as heavy a blow as any of ship’s officers have been in. I certainly cannot imagine more wind or a bigger sea. I heard that at 3.30am the 2nd mate and a hand went aloft to see to upper fore topsail and that on coming down he stepped into lee scuppers, which were full up with water. He is a short fellow and was up to his neck. That I think gives me some idea of the sea shipped on broaching to, and we in ballast.”

The Old Man – who was 64 and had been up all night – was laid up with cramp in the chart house, and the foremast staysail was a rag.

The hurricane squalls and strong gales continued for three weeks, almost without let up. Stone and de M. would tell the newspaper reporters waiting in Newcastle that they were both “ardent lovers of the sea” but neither of them ever wished to undergo such an experience again.

Monkbarns was one of five sailing vessels that arrived at Newcastle on the weekend of 5th July 1913, including the full-rigged Ben Lee, which had sailed from Buenos Aires two weeks before her. All had suffered. Ben Lee’s lower topsail had carried away and the foresail was blown to pieces. Kilmallie, from Santos, lost a lifeboat and her ballast shifted. The barque Lysglimt, from Natal, was knocked onto her beam ends when her ballast shifted, and the crew spent three death-defying days in the hold trying to right her, the Sydney Morning Herald reported.

Despite or possibly thanks to the hurricane, Monkbarns had made the passage in 52 days, to Ben Lee’s 67. Our man on the docks reported that two of Monkbarns’ crew had been injured and had been “attended by Dr M Stone, a passenger”.

Up in Newcastle, (where they went because there was smallpox in Sydney and the city was about to be quarantined), the Newcastle Morning Herald & Miners’ Advocate produced a much juicier report, headlined “An interesting visitor”.

Dr Stone, it said, had been imprisoned by Germany for spying the previous year (shades of Erskine Childers‘ The Riddle of the Sands). Dr Stone did not deny it. He had been one of a party of five well-to-do British yachtsmen – including the marine artist Gregory Robinson and the engineer William Richard Macdonald, who happened to have patented a nifty bit of submarine technology. They had attracted unwelcome attention from the German military authorities by happily photographing naval installations along the Kiel canal. It had taken them five days to talk themselves out of jail.

During the war that broke out less than a year after Monkbarns’ arrival in Newcastle, Stone would serve in the Royal Army Medical Corps. He became an eminent radiographer, with an obituary in the British Medical Journal in 1941.

The Kineto company, however, folded in 1923 and de M died in New Zealand in 1928, the year after Monkbarns was hulked off Corcubion, in northern Spain.

Stone carried on yachting all this life. Perhaps he even shot more films. But what became of his footage of working life aboard a British ship in the last days of sail remains a mystery.

*

An edited version of this article appeared first in The Cape Horner magazine, the journal of the International Association of Cape Horners. August 2015.

Photographs by Eugene Bainbridge, who was Monkbarns’ last apprentice during her final voyage, 1924-26. He joined her in Newcastle NSW, having steamed out from the UK third class aboard the P&O passenger ship Barrabool. He was then 19, the privately educated only son of a maritime insurance broker from Surrey. He had a Leica camera and for two years he kept a diary and took pictures of life aboard. Neither the diary nor the photographs were ever published and Eugene never went back to sea. These previously unseen views are made available by kind permission of his family.

Next: Worse things happen at sea

Previously – Flowers in Hong Kong, Medals in the Post iii

Read from the start:

A sailor’s life – beginning, middle and end

Written by Jay Sivell

May 8, 2016 at 2:10 pm

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Historical postcards, Isle of Wight & Sivell family, Other stories, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, Uncategorized, WWI

Tagged with apprentice, Ben Lee, Bert Sivell, Captain James Donaldson, Cinematograph, Dudley Macauley Stone, Eugene Bainbridge, handelsmarine, health at sea, injuries in sail, Isle of Wight & Sivell family, John Gilbert Eveleigh-de Moleyns, John Stewart & Co, Kilmallie, koopvaardij, last days of sail, Leslie Beaver, life at sea, Lysglimt, marina mercante, marine marchande, merchant navy, Newcastle NSW, passengers on sailing ships, seamen's pay & conditions, square rigger, storms at sea, Tall ships, unpublished footage of sea, Videx, William Chapman, windjammer

A Sailor’s Life – 78. Flowers in Hong Kong (Medals in the post III)

Wreath to the men of the Shell oil tanker Chama, lost in the Atlantic on 23 March 1941, including the 38 Chinese crew

It is cold in the Atlantic in March at 2am and 57 names take a long time to scatter one by one. The wind whipped round my oilskins, snatching at the slips of paper that filled both pockets as I read each name before releasing it to the sea. “Hubert Sivell”, who left a wife who liked to sing and two bright children he hardly knew, and a row of winter cabbages where his lawn had been.

Did Chong Fai the pumpman, 44, have a wife? Did Tiew Khek Guon the carpenter, 41, leave a child far away who would never know what became of him? Did the parents of Foo Yee Yain, 23, the pantry boy, ever know their son had not willingly abandoned them?

Even now, 70 years after the end of the second world war, no one can tell me precisely how many merchant seamen were killed. The Commonwealth War Graves Commission commemorates 36,507, but it admits records in occupied countries were lost or destroyed and that some figures may overlap.

Canada commemorates 1,437 Canadian merchant men lost at sea. Occupied Norway, Denmark and Belgium account for approximately 6,513, not including those who died in captivity. The Netherlands records, on top of the 1,914 Dutch casualties, 1,396 “lascars, Chinese, Indonesians and other foreigners” lost from its ships. America honours 5,302, including its merchant navy gunners. And so forth.

Counting those who died of injuries ashore or in prisoner of war camps, the total is 47,000 at the very lowest estimate*, or roughly 10 men for each and every allied ship lost, commemorated in cemeteries or memorials from Halifax, Nova Scotia, to the Pacific.

The CWGC memorial in Hong Kong, opened in 2006 and inscribed with the names of the 941 Chinese casualties of the First World War and 1,493 from the Second World War, whose graves are not known.

It had taken me a long time to realise the 15 names on the brass panel I had been taken to see on Tower Hill in London as a child could not be the whole crew of my unknown grandfather’s last ship, the Shell oil tanker Chama. And longer still to realise the missing ones were almost all Chinese.

The men who died with Bert Sivell that murky night in March 1941 are commemorated separately on at least six different memorials to men with “no grave but the sea”: in London, Liverpool, Plymouth, Chatham, the military cemetery at Brookwood, Surrey, and Hong Kong, where an arch erected in 1928 was amended to include the Chinese who died “loyal to the Allied cause” in both world wars.

In 2006, the Commonwealth War Graves Commission set up a new memorial in the Stanley Military Cemetery, Hong Kong, inscribed with the names of 941 Chinese casualties of the First World War and 1,493 from the Second World War whose graves are not known. Yet Shell alone lost 1,008 Chinese merchant sailors between 1939 and 1945, according to WE Stanton Hope’s Tanker Fleet, published in 1948. Two of Shell’s Chinese seamen were awarded Distinguished Service Medals, 17 merited British Empire Medals, nine were officially commended or mentioned in dispatches, a pumpman called Chan Chou was awarded the Lloyd’s War Medal for Bravery at Sea, three were given the Lloyd’s Bronze Medal for Meritorious Service, and three were awarded Bronzen Leeuwen by the Dutch government in exile.

Memorials maintained by the CWGC in Bombay and Chittagong commemorate in Hindi and Bengali respectively some 6,000 Indian, Adenese and East African merchant seamen with no known grave. Many of them too served on the oil tankers that kept RAF planes in the air, and on cargo vessels bringing in food and passenger liners transporting troops. Only a very few are included under the name of the ship they went down with at Tower Hill. Yet they were – as the Queen put it, opening the sunken garden in 1955 – part of the “splendid company of brave men and women from many nations… who served in fellowship under the red ensign”.

Their exclusion is administrative, apparently. After the war everyone wanted their own memorial, according to the CWGC, which records the particulars of some 1,767,000 commonwealth country casualties of both world wars.

The memorial arch at the entrance to the Botanical Gardens in Hong Kong, commemorating Chinese lost serving ‘the Allied cause in two world wars’.

Tower Hill was extended to commemorate the men and women of all nationalities who were lost serving on ships registered to or chartered by Britain and the Commonwealth and were registered living in Britain. The panels include Asian and Arabic names, Dutch, Norwegians and Greeks, as well as Trinidadians, South Africans and New Zealanders.

Chama’s men, though, cut off from their families in Hainan and Xiamen after the Japanese invasion in 1935, were registered to boarding houses in Singapore and not technically domiciled in Britain. Like lost souls they ploughed to and fro across the Atlantic, unable to go home.

“It wasn’t their war,” one old merchant sailor told me when I asked about the Chinese shipmates who had shared his lifeboat.

In 1952 my grandmother reluctantly had Bert Sivell declared dead. She still did not know what had happened to him, and the convoy records revealing the ship’s final distress message and position did not open until 1971. She had been dead herself for nearly 20 years when fiddling on the internet one evening I found a Cyprus-registered container freighter that crossed the Atlantic almost exactly where Chama was lost. That it was a German-owned vessel with a German master seemed only poignantly appropriate.

Research often takes on a life of its own. Belated curiosity about my grandfather’s life, and his death, and his ship, and the men he sailed with opened unexpected cans of worms: segregation, racism and discriminatory pay and conditions for Chinese crews being just the start. They were paid half the rate of white crews and in the US armed “Bogarts” prevented them even going ashore. In the UK, they faced union hostility as cheap labour for “under-cutting” pay, but when they unionised and struck back they often found themselves blacklisted by the shipowners. Back home, civil war raged between the Kuomintang and the Communists, cutting families off from the breadwinners far away. The seamen stayed put, trapped. Some found consolation and set up new families in Limehouse and Liverpool, but in 1946 as Britain’s troops demobbed, the extra foreign labour was deemed surplus and the Chinese seamen were “repatriated”, by force. There’s a group of half-Chinese children in Liverpool who never knew what happened to their fathers. One day the men simply vanished, rounded up in the street and put on waiting ships, surplus seamen sent “home” to Singapore. Union activists (or “undesirable elements”) were prevented from returning, although some made it back in the 1950s – to a mixed welcome from the women who thought they’d been abandoned.

Interviewing an old British seaman one afternoon, I learned that in the late 1930s my grandfather had ordered his junior officer to remove and destroy any red letters in the Chinese crew mail. He didn’t want “communist” propaganda coming aboard, but I was aghast wondering how many lonely men had been ruthlessly denied messages in lucky red envelopes from the loved-ones far away. Curiosity about the families led me to the group in Liverpool and their bitter-sweet tales of tracing – or not – their missing Chinese dads.

And that’s partly why, 60 years after the battle of the Atlantic was won I went to sea aboard a container freighter, with a biodegradable wreath of twigs and flowers, and a full list of the names of my grandfather’s men.

Flowers laid by the family of Captain Sivell, commemorating the Chinese crew of the Shell oil tanker Chama, who shared his fate in the Atlantic in March 1941

My local vicar and the Seamen’s Mission in Liverpool suggested suitable psalms which I murmured into the wind and spray. A friend had phoned Hong Kong for advice from funeral directors on appropriate words or prayers for the Chinese crew, but they could suggest none. So, reluctant to let me go out empty-handed, one of the fathers in my daughter’s primary school class wrote a poem in Mandarin which he delicately inked on to paper ribbon and they taught me how to say “We shall remember” in Cantonese. It was not much of a funeral service, and it was 62 years late, but it was the first time all my grandfather’s men had been commemorated together.

So far I have not made it to Hainan or Xiamen or even Singapore, but in March 2015, one of Bert’s great granddaughters – passing through Hong Kong on her gap year travels – sought out the ancient arch at the entrance to the Botanical Gardens and placed fresh flowers and a message in English and Chinese that the florist kindly translated for her: “In memory of the Chinese crew of the oil tanker Chama, lost with all hands on March 23rd 1941. From Captain Sivell’s family.”

*

Full list** of the officers and men of the Shell oil tanker Chama, lost 23 March 1941:

HS Sivell, Master, 45

Alfred Gray, Chief Officer, 26

William Howard Hume, 2nd Mate, 23

Ian Cyril Cunningham, 3rd Mate, 22

Alfred Leonard Francis Williams, Chief Engineer, 40

Joseph Emmerson Black, 2nd Engineer, 41

Andrew Hughes McKnight, 3rd Engineer, 28

Frank Cameron Miller, 4th Engineer, 25

Peter Hammill Manderville, 5th Engineer, 20

John Walker, 5th Engineer, 20

Frank Wellings, 5th Engineer, 19

Richard James Hilhouse, apprentice, 18

Rothes Gerald Novak, apprentice, 18

Cornelius William McCarthy, W/O, 42

Michael Timothy Murphy, 2nd W/O, 24

Tow Siong Kong, 42, Bosun

Ngai Ah Sai, 44, Storekeeper

Ah Tee, 33, Quartermaster

Wong Ah Chong, 36, Quartermaster

Leng Ah Moy, 35, Quartermaster

Lee Ah Chay, 29, Quartermaster

Juan Seng, 35, Chief steward

Joe Tin Fatt, 28, 2nd steward

Wong Ah Tay, 33, sailor

Tang Siew Luk, 24, sailor

Lin Loon, 31, sailor

Ee Ong Fatt, 30, sailor

Lim Sin Keng, 41, sailor

Kin Kwang, 24, sailor

Chao Ah King, 30, sailor

Ting Meng, 28, sailor

Teong Ah Tay, 32, sailor

Chan Sun Sang, 23, sailor

Tan Tian Teck, 40, Chief cook

Mew Po Heng, 33, 2nd cook

Ling Ah Chaw, 34, Sailors’ cook

Wong Choo, 30, Firemen’s cook

Wong Tung Kuam, 21, Sailors’ Boy

Tiew Khek Guon, 41, carpenter

Chong Song, 38, no 1 fireman

Choung Hee, 25, no 2 fireman

Li Kan, 42, no 3 fireman

Thoe Foon, 27, donkeyman

Chong Fai, 44, pumpman

Mik Kia, 37, fireman

Lan Kan, 37, fireman

Siong Wah, 40, fireman

Chong Wo Fook, 31, fireman

Fung Kim, 27, fireman

Lee John San, 32, mess room boy

Ee Muay, 35, mess room boy

Foo Yee Yain, 23, pantry boy

Sim Tie Jong, 26, saloon boy

Albert Victor Wincup, RN, 44, Chief Petty Officer (DEMS gunner) – Chatham Naval Memorial

Bertram Smith, RN, 20, Able Seaman (DEMS gunner) – Plymouth Naval Memorial

James Kennedy, 22, British Army, Fusilier (DEMS gunner) – Brookwood Memorial

Daniel Holmes, 21, British Army, Fusilier (DEMS gunner) – Brookwood Memorial

*Re national figures for merchant navy losses – all information gratefully received.

**Including two not on the Registry of Shipping and Seamen list.

Previously – The Medals in the Post ii/ Medals in the Post

Next – A doctor aboard (1913)

Read from the start:

A sailor’s life – beginning, middle and end

Written by Jay Sivell

June 25, 2015 at 1:17 pm

Posted in 3. Shell years - 1919-1939, 4. The war at sea, 4. The war at sea, 1939-, Chinese seamen, Other stories, Seafarers' wives, Shell oil tankers, WWII

Tagged with Anglo-Saxon Petroleum Company, Battle of the Atlantic, Bert Sivell, Chama, Chinese sailors, death at sea, handelsmarine, Isle of Wight & Sivell family, koopvaardij, life at sea, Liverpool Chinese, marina mercante, marine marchande, merchant navy, oil tankers - Shell, seamen's pay & conditions, Second World War, Shell oil tankers, Shell tankers, Shell's Chinese sailors, war at sea

A Sailor’s Life – 77. The medals in the post II

Flowers commemorating the Chinese crew of the Shell oil tanker Chama, lost with all hands in the Atlantic on 23 March 1941. Placed at the memorial arch in Hong Kong by Captain Sivell’s great granddaughter, March 2015

It is 74 years tonight since Captain Hubert Sivell of the oil tanker Chama and all his 52 British officers and Chinese crew vanished into the cold mid-Atlantic. On the “winter garden” of U97 the lookout watched the tanker sink, burning, stern first into the sea and the commander, Udo Heilmann, noted “Laufe mit sudlichen, dann westlichen Kurs ab…” (depart on southerly, then westerly course).

Three months later an empty life boat was picked up west of Ireland and brought into Cork. It had “Chama” on its transom.

There were no survivors.

*