Posts Tagged ‘Sailing ship apprentice’

A sailor’s life – 83. Foaming water, clean living

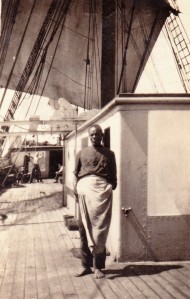

Scantily-clad crew aboard Monkbarns, 1926 – “It then proceeded to rain in torrents and all hands could be seen on deck with next to nothing on, washing clothes. A great day for the sailor’s gear,” Eugene Bainbridge, 6 May (courtesy estate of Eugene Bainbridge)

Descriptions of rounding Cape Horn in sail tend to dwell on ice and howling winds and split fingers and harrowing near-misses. The doldrums, through which ships from Europe must pass to get to the southern hemisphere, feature only as a spot where vessels languish becalmed. The very word has drifted into the English language meaning “inertia, apathy, listlessness, malaise, boredom, tedium or ennui”.

The sheer hard work – and the sailor’s rare luxury of washing himself and his smalls in unlimited fresh water during rain showers in the doldrums – is therefore usually overlooked. This charming reminiscence about life on the German four-masted barque Peking on the Chilean nitrate run in 1928 comes from former Laeisz Flying P-line master Hermann Piening, one of many “grand old boys” interviewed by Alan Villiers, (quoted in The War With Cape Horn):

… And then the trades! That remembered paradise of the ocean sailing-vessel life when all the hardships are forgotten. Through the blue sea the keen cutwater of the sleek, big Peking rips day after beautiful day, scaring the wide-eyed flying fish with the roll of foaming water that forever races at her bow. Here the sailor may feel the essence of harmonious beauty between his ship and the sea. But nothing lasts. The doldrums come with their nervous cat’s-paws of fleeting airs, their sudden swift squalls, their deluge after deluge of almost solid rain.

“You are not to think that we are dealing here with a domain of absolute lack of wind,” says Piening. “That seldom exists, for even slight variations in pressure must always result in movements of air. But the wind is uncertain and faint here. The navigator who is not continually ready to make use of even the lightest breath can spend weeks in this uncomfortable hothouse. There is no rest for the sailors. There are watches in which they hardly get off the braces for ten minutes.

… “There is only one pleasant thing about this region: it rains frequently. In a compact mass, the water falls from the blue-grey sky. Everything and everyone aboard revels in soap and water, for the fresh-water store of a sailer is limited and the duration of the passage most uncertain. A sort of madness seizes everyone. Clad only in a cake of soap, the whole crew leaps around and lets itself be washed clean by the lukewarm ablution. Filled with envy, the helmsman looks at the laughing foam-snowmen into which his comrades have transformed themselves. Everyone pulls out whatever he can wash and lets the sea salt get rinsed out thoroughly. By night the heavy lightning flashes of this region present a splendid show. Often the heavens flame copper-red and sulphur-yellows, and hardly for a second is the vessel surrounded by complete darkness. At times St Elmo’s lights dance upon the yardarms.”

[Editor’s note: The Laeisz four-master Peking is back in Europe after languishing rather unloved in New York for four decades. Yay! A major operation to get her back across the Atlantic in a floating dock last year is now being followed by a major refurb in Wewelsfleth, north of Hamburg.]

Alan Villiers talking to Captain Hermann Piening, ex Laeisz “flying P-line”, from The War with Cape Horn (1971)

Written by Jay Sivell

August 18, 2018 at 2:45 pm

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Other stories, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, Uncategorized

Tagged with Alan Villiers, apprentice, Chilean nitrates, Doldrums, Eugene Bainbridge, F Laeisz, four-masted barque, fresh water at sea, handelsmarine, Hermann Piening, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, marina mercante, marine marchande, merchant navy, Peking, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, seamen's pay & conditions, square rigger, Tall ships, windjammer

A sailor’s life – 80. Worse things happen at sea: the steward’s story

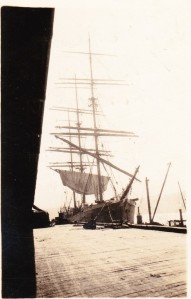

Monkbarns unloading nitrates in Walsh Bay No 10 Sydney, May 1925 (Copyright estate of Eugene Bainbridge)

David Morris called himself a journalist, a writer. He’d been on the lookout for a job on a square rigger for months before he heard of Monkbarns in Sydney in June 1925. He wanted “atmosphere” for some historical sea stories he was preparing to publish, he told the Newcastle Sun as the ship loaded Australian coal for South America. He wanted thrills, he wanted to “see the Pacific at its worst”.

Around him on deck, eyes slid away. “Some of the crew, with that superstition born in seamen, are inclined to regard him us a hoodoo,” the reporter noted.

Three weeks earlier Morris had shot across to Walsh Bay, Sydney, where the ship was discharging nitrate, and buttonholed the mate, offering himself in any capacity at a nominal wage. The mate had said “Nothing doing”, but as he trudged off down the gangway, they’d had a rethink. If he really wanted the experience, said the master, he could come along as a general helper at £2 a month (about £1,000 per annum today.)

Was it a cheap shot they’d expected him to refuse? Morris called himself the Captain’s steward, though he appears on the crew list as Cabin Boy, but pay for a seaman was £10 a month, not £2. Then again, as steward or “boy” he didn’t have to go aloft in all weathers or stand his trick at the wheel. He was a housekeeper, minding stores and dispensing first aid.

“Yesterday Morris was caught sewing his shirt, with stitches that would disgust a housewife, on the steps leading to the poop deck. He is a well-built man of 25, but he looks more like 30. The small moustache on his upper lip, and the tan shoes and the tweed suit already soiled by work in the galley, looked strangely out of place there,” said page 6 of the Newcastle Sun.

Movie poster for The Ship from Shanghai released in 1930 (http://adventures-of-the-blackgang.tumblr.com/

London-born Morris had visited most ports in the world as a passenger, and had slept in some of Australia’s best hotels and its least inviting parks in his quest for “atmosphere”, readers learned. He had been inspired to join Monkbarns by the runaway success of a sea thriller published the previous year by another young Australian journalist, Dale Collins. Ordeal is based on a round-the-world trip Collins made aboard the motor yacht Speejacks as historian to the US cement magnate Albert Younglove Gowen, who happened to be on his (second) honeymoon. The novel – about seamen turning on their idle rich passengers – was filmed in 1930 as The Ship from Shanghai, with Louis Wolheim as the ship’s crazed steward who holds them all hostage.

Morris was quite frank about what he was up to; there were men on Monkbarns who had had remarkable experiences, he told the newspaper, and he wanted to “chase up” some of those real-life stories. But he seems to have fallen short on listening. This may have been a world of horny-handed hard cases risking life and limb in all weathers aloft, but they still wouldn’t set sail on a Friday, or whistle for fear of challenging the wind, or even say “pig” out loud.

Of the 28 men and boys who had left Liverpool in March 1923, one was dead – a 19-year-old apprentice lost lashing down an escaping sail during a hurricane – two had been left behind in hospital injured, and two more would die before they dropped anchor back in the Thames in 1926.

Monkbarns 1923 securing lifeboats under heavy seas off the cape (probably photographed by 3rd mate Malcolm Bruce Glasier)

By June 1925, only the captain, the mate, “Sails”, a couple of ABs and the older apprentices remained of the original company. It was they who had faced down disaster on the passage out, when a hurricane south-west of Good Hope knocked them so badly that the cargo shifted. With the lee side of the ship 12ft under and green seas raking the deck, it was they who had risked their lives deep in the hold, shovelling rock salt uphill for three days to try to right her. Young Cyril Sebun was lost off the upper topgallant yardarm while they laboured. But nothing could have been done to save him. The boats were all smashed.

Eventually, they put into Cape Town in distress – a first for Captain William Davies. “During my forty years of service in sailing ships I have never had an experience that can in any way compare with this recent one, and to be quite frank, I should not like to pass through a similar ordeal again.”

On arrival in Australia, three seamen deserted – abandoning their pay – and Morris’s predecessor killed himself with an overdose of chloroform. He had been drinking heavily, the inquest noted. He was buried in Stockton NSW, where some of his former shipmates from the SS Argyllshire called the following spring. They sang Welsh hymns at his grave, and laid artificial flowers. They knew.

So, it was not surprising that Morris’ taste for ill winds made his shipmates uncomfortable and by the time Monkbarns had been at sea for two months, things had turned nasty.

Three entries from the diary kept by one of the apprentices, Eugene Bainbridge, offer a snapshot: 23.8.25. Sunday. Played Bridge all day and was 600 up to finish. It has been quite parky lately and it was anything but warm at the wheel from 12-2 tonight. Course ENE, on starboard tack. Shaved David Morris’s beard in half deck after putting him forcibly on the floor. He seemed a bit peevish and didn’t play ‘Vingt et un’ very well afterwards. The job we made of his beard wasn’t very good.

24.8.25. Monday. Clear, calm, sunny, fresh. Doing about 2-3 knots. Course ENE. ‘Maurice’ came in for about two minutes tonight. He seemed to know that there was something in the air and beat it.

The Pelican Society photographed by Eugene Bainbridge – Newcastle-Callao 1925 (Copyright estate of Eugene Bainbridge)

25.8.25. Tuesday. A night of revelry of a peculiar sort. The subject was ‘Maurice Moscovich’. Notices were posted on the half deck doors inviting you to a singsong to be held in the fo’c’sle at 6.30pm. The Mate was particularly asked to refrain from blowing 2 whistles and when told why, was quite sympathetic. At 6.30 sharp, we met and the subject [Morris] had wandered into the gay party.

It was a bluff. He was to be seized in the middle of its proceedings and tried by the chief Pelican and his confederates. All passed off as planned and the victim was found guilty of not supplying the fo’c’sle with molasses and duly sentenced to have his port beard and starboard ‘tache shaved off. Cold water was used to emphasise the gravity of the act, and Bill Hughes, the Court Hairdresser, operated.

But worse was to come, because Morris evidently put up resistance to the assault, verbally if not physically. Bainbridge, a 21-year-old ex-boarding school boy from Maida Vale, London, records that the victim was deemed to have been “unduly insolent” to his tormentors – and a vote for death by dropping over the after part of the poop was passed.

Maurice Moscovitch as Shylock at the Royal Court, London, 1919 (From: http://exhibitions.europeana.eu/exhibits/show/yiddish-theatre-es/jml-las-obras/item/130)

It is possible that there was more than a little anti-Semitism in this “hazing” as Maurice Moscovitch was a well known Russian Jewish stage actor that summer wowing Australian audiences with his Merchant of Venice and Morris’s middle name was inscribed on the crew list as Isidor. Bainbridge had been to see Moscovitch at the Criterion theatre while Monkbarns was in Sydney.

More worrying still, the punishment meted out – for poor stewardship of the few treats that made the ship’s diet of salt meat and pulses bearable – apparently had the backing of the Master and the Mate. Bainbridge writes: We next trussed him up in a sack etc and took him aft for the mate’s inspection.

The procession marched solemnly back singing ‘For it’s a Lie’. Prisoner was next trussed up again (more securely) and taken forth to his execution. Maurice was marched up on to the fo’c’sle head and lowered away over the break. The wash tub was underneath and someone was making a noise like water. The stunt worked so far and when about a foot off the deck, the word was given and Maurice was dropped!!! He arrived in a heap at the side of the ‘donkey’ [steam winch] amid cheers and benedictions from the High Priest.

Had Morris believed his hostile playmates were actually dropping him gagged and bound into the Pacific? It seems more than possible, but he showed his mettle by joining them in the fo’c’sle, where proceedings continued as a “sing song”, and reciting a chunk of Kipling for the company. Whereupon everyone joined in a hearty chorus of “For he’s a jolly good fellow” and peace descended. Bainbridge wrote: The Old Man and Mate were both observed to be enjoying it uncommonly.

Many years later, “Bill the Court Hairdresser” – by then Captain William Hughes, sir – remembered David Morriss [sic] and his quest for atmosphere. “He got it all right, and I’m sure that what he went through before reaching London would fill two or three books,” he told AG Course, chronicling the history of the John Stewart ships for his book The Wheel’s Kick and The Wind’s Song.

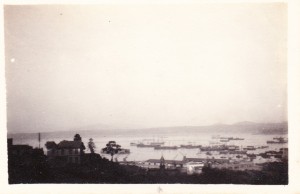

View of Valparaiso harbour with Monkbarns marked by apprentice Eugene Bainbridge with an arrow at the bottom (copyright estate of Eugene Bainbridge)

Two months later, just outside Valparaiso, he was still annoying the apprentices (Dave joins us, and we are bored to a standstill with his platitudes!) but he’d graduated from ‘Maurice’ to Dave. And in port, Dave showed a pleasing openhandedness with the ship’s stores as the apprentices rowed around visiting and being visited by boys from neighbouring ships. (Dave got us some stores and there was plenty of scoff. He unfortunately spoilt this good turn by telling some of his tall yarns.)

However, as soon they put out to sea again and rationing restarted, the moans resume. 9.3.26. Dave wants to substitute sugar for molasses instead of substituting jam. This is not a fair exchange as sugar doesn’t go well with bread and butter! 5.5.26. Dave has been making mistakes with the weighing out of the butter and the tins containing so painfully small a quantity we complained and found we were getting less than our whack!

Happily, nine months after Morris’s sentencing by the Pelican Club, the horseplay had become rather more inclusive, if no less rough. By then, Captain William Davies was dead in Rio de Janeiro, the Mate was the new Old Man and the ceremony as Monkbarns passed Lat 0° 00’ 00” was a more or less welcome letting off steam after a very trying few months fighting their way round the Horn with the dying man refusing to put into port.

Young Bainbridge had a ringside seat. 9.5.26. Sunday. Crossed the Line last night. We all ‘felt the bump and noticed that the ship was going faster downhill!!’ At 1.30, I was let into the secret by Bill that we ‘offenders’ had to ‘go through it’. The Old Man had made some pills of ginger, glycerine and several other ingredients and covered them with sugar (of which there is a very large quantity aboard from Rio.) Jim had made some very ‘choice’ mixture of tar, tallow, soap, Melado (molasses) and red lead.

Monkbarns, Neptune’s court May 1926 – crossing the Line. Neptune and wife right, Dave Morris and Eugene Bainbridge among the tarred six on the left (copyright estate of Eugene Bainbridge)

In time honoured tradition, Neptune appeared over the side clad in oakum and bearing a huge trident made from the mast of the for’rard boat, accompanied by his Wife, his Barber, his Parson – in a lead foil cassock and paper collar – and his Doctor carrying the bag of pills. They set up court on the main hatch.

Bainbridge and Morris were among six “first trippers” the god of the sea wanted to inspect for fitness.

I was first blindfolded and then marched to the main hatch, falling over several ‘lines’ drawn across the deck. We had made the washhouse door fast and they had to break the handle off to get in. I was first asked by Neptune why I had done this and if I had crossed the Line before and why I hadn’t been ‘put through it’!

I then kissed his wife’s foot, which was covered with tar and was then shaved using the mixture, getting plenty of it in the mouth. I received the pills and spat them out. At a second shot, I managed to conceal one behind my tongue but before I could remove it my mouth was sore! I finished up being tipped backwards into a tub of water and then liberated. After I had seen two or three others done I went onto the boom and caught a 24lb bonito, which we had for tea. The proceedings broke up with all hands ‘splicing the main brace’.

They were back in the northern hemisphere after three years away, and “home” suddenly seemed closer. But Monkbarns’ adventures were not over. Progress was slow. Supplies ran out. By 450 miles off the Lizard they were down to rice and ersatz bread, but once into the shipping lanes an obliging German steamer provided relief.

They brought the boat alongside and the provisions pulled aboard: three sides of bacon, two hams, two cases of spuds, three sacks of flour and about 16 tins of Argentine boiled beef (we had some for tea and it was excellent), a certain amount of margarine and butter for the cabin, also lard and Dutch evaporated milk. Then the Cook gave us curry and rice for breakfast!!!!!!!! It was nearly the last of him.

But two weeks later they were still 12 miles off Portland Bill, and “reduced to rice, tea and a little jam and bread”, according to another unpublished diary of that voyage, by able seaman Dudley Turner. “Not had a smoke for weeks, which makes matters a lot worse.” And the Old Man was refusing to flag down any more ships.

When they picked up the pilot off Dungeness and it was discovered he handed out cigarettes for good steering – the first tobacco seen aboard for weeks – there was a rush to relieve the wheel frequently. “Never had such good steering been seen before by the old ship,” wrote Course. But they were so undernourished that the tug crew had to help them haul the hawser aboard.

At 6pm on 10 July 1926, Monkbarns dropped anchor off Tilbury. The pilot presented them with a sack of potatoes and Bainbridge records a “memorable feed of sausages and boiled spuds!!! Never was a meal so appreciated”.

The following day they were towed up to Charlton Buoys, a vessel from a bygone age gathering crowds on the banks, and there the crew were paid off.

And there the story ends. Monkbarns was sold “foreign”, and towed to Corcubion in northern Spain to end her days as a coal hulk. Eugene Bainbridge abandoned the apprenticeship for which his father had shelled out £42 and never went to sea again. What became of David Morris I cannot tell. Bill Hughes thought he’d gone in to radio in Melbourne. If he ever wrote up his historical sea stories, neither AG Course nor I could find a trace.

Bizarrely, the real thrill-seeker aboard Monkbarns that trip turned out to be the youngest apprentice, 17-year-old Len Marsland of Brisbane. After rounding the Horn in sail, in 1929 he pops up as a member of Sir Douglas Mawson’s Australian Antarctic expedition. He worked as a prison guard in Canada, chased the explorer Sir Hubert Wilkins across the Atlantic in an attempt to sign up for his submarine expedition under the polar ice, reappeared in Reykjavik, erecting a signal station, and then back at sea as an officer on an icebound freighter in the Baltic and facing down machineguns in a Russian Black Sea port. Tragically, Marsland’s adventurous career was short. While working as a stuntman for Sir Alan Cobham’s famous flying circus in 1935 his parachute failed to open. He fell 1,000 feet and died in Esher, Surrey, aged just 27.

Previously: A doctor aboard 1913

Written by Jay Sivell

May 29, 2016 at 12:39 pm

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Other stories, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, Uncategorized

Tagged with AG Course, apprentice, cabin boy, Captain Bill Hughes, Captain William Davies, Cyril Sebun, Dale Collins, David Isidor Morris, discipline and desertions, Eugene Bainbridge, first tripper, Frederick Leonard Marsland, handelsmarine, John Roberts, John Stewart & Co, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, marina mercante, marine marchande, Maurice Moscovitch, merchant navy, Newcastle NSW, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, seamen's pay & conditions, ship's steward, square rigger, SS Argyllshire, Tall ships, The Ship from Shanghai, Valparaiso, Walsh Bay Sydney, windjammer

A sailor’s life – 74. Monkbarns: Britain’s last Cape Horner?

She was obsolete the day she slipped into the Clyde in June 1895: a steel-hulled, full-rigged, three-masted windjammer launched into an age of engines barely two years before Rudolf Diesel changed the world of shipping forever.

The flax mill owner who had commissioned her, Charles Webster Corsar of Arbroath, named her Monkbarns after a local character from a Walter Scott novel (The Antiquary) and demanded everything of the best. The decking and rails were of teak, the accommodation for officers and crew particularly fine. “Her outfit includes all the modern appliances for the efficient working of such a vessel,” reported the Lennox Herald, the Saturday after she was floated.

As a final touch, Corsar even gave her a little white Pegasus figurehead – which would make Monkbarns and her “Flying Horse line” sisters, Fairport and Musselcrag (1896), recognisable around the world. It was not whimsy but canny branding: Corsar’s flax mills and manufactory in Arbroath supplied the sailing ship canvas sold by the family’s cadet branch, D. Corsar of Liverpool – every bolt of it stamped with their trade name, Reliance, and a little flying horse.

The Lennox Herald did not mention the figurehead, nor any further detail, merely remarking that the naming ceremony was carried out by Mrs David Corsar, Jnr, of Cairniehill, Arbroath.

The launch of Charles Corsar’s full-rigged ship Monkbarns, reported in the Lennox Herald, West Dunbartonshire, Scotland, in June 1895

In fact, the launch by Messrs Archibald McMillan & Son (Limited) merited only a single paragraph in a round-up of Dumbarton news that week, wedged between reports about two men being fined 20 shillings each for driving without lights and a rumour in the Glasgow Herald that the Union Steamship Company of New Zealand was buying five new steamers, possibly from Dennys of Dumbarton, which had “built the greater number of vessels for the line, and will probably run a good chance of getting at least some of the work”.

The reporter’s description of Monkbarns having “all modern appliances”, however, echoed down the years. Frank C. Bowen wrote in 1930 that she had “every modern labour-saving device for working the cargo and sails” (Sailing Ships of the London River), and most subsequent authors took him at his word. Yet Monkbarns’ apprentice boys might have considered the matter rather differently.

Like every other sailing ship of her age, she had neither light nor heat. The White Star liner Majestic, completed five years before Monkbarns, catered for 4,100 passengers with an à la carte restaurant and Pompeian swimming pool. But Monkbarns had kerosene lamps and the galley fire (weather and cook permitting). There was no electricity for refrigeration. Fresh vegetables and fruit barely lasted out of sight of land. Potatoes were stored in the dark and given a haircut every week or so. Meat was “preserved” in casks of brine. Margarine came in tins. Coffee was drunk black. Even the water was rationed.

The boys were trainee officers – set apart from the sailors in the fo’c’sle and their masters in the saloon aft by virtue of being unpaid. They lived in the “half-deck”, an iron bunkhouse amidships, which on Monkbarns latterly consisted of two rooms and a corridor with doors either end so that entry could always be from the lee side of the ship while at sea. It was an ice box in the winter and an oven in the tropics, but it had a skylight exit and a “monkey bridge” to the poop that was popular in heavy seas, when the decks were often awash to a depth of two feet or more.

Monkbarns’ half-deck had bunks around the walls on three sides; a bare deal table with raised sides in the middle – flanked by boot-marked benches; a pot-bellied iron stove fed with coal filched from the cargo; and a battered cupboard in the corner divided into lockers, with fancy knotted rope tails for handles. There was a mirror, mottled with damp, and a single smelly kerosene lamp swinging in gimbals.

The bunks were narrow, with high boards along the open side to stop the sleeper rolling out as the ship pitched, and coloured pictures – often of girls, sometimes a country scene – pasted to the surrounding bulkhead by previous occupants. By some hung a canvas “tidy”, containing needles and cotton for repairs. The apprentices had to do all their own own mending, darning and cobbling. Laundry had to be done in salt water, in precious time off and only when there was chance of the garment drying.

New boys would arrive each trip with shop-smart dungarees and new straw mattresses, which the old hands in patched gear would regard balefully. Their own bunks were bare except for blankets, and within weeks the new boys learned why, when the “donkey’s breakfasts” had to be tossed overboard crawling with bed-bugs. Wet oilskins stayed wet, and chafing salt water boils were endemic.

Aboard Monkbarns “all modern appliances” did not include a donkey engine until the mid-1920s, and in many ports her cargo was loaded and discharged by hand – the boys shovelling Australian coal out through the hatches basket by basket to waiting lighters off the coast of Chile, until the dust grated in their lungs and ground itself under their skin. As the last basket was hoisted out there would be shanties and a well-earned tot of whisky – unless the Master was a teetotaller.

Then work would begin again, scouring out the filthy holds for the arrival of saltpetre, 200lbs a sack, which had to be swung aboard and stacked one by one in pyramids below. Monkbarns took about 3,000 tons, or 34,000 bags. The air would be like soup. Out in the Chilean anchorages, in holds lifting and falling in the long Pacific swell, the evaporation from the bags was known to kill rats and even woodlice, and ship’s cats would lie down in dark corners and not wake up.

Guano was considered worse, a throat-catching green powder of ancient bird droppings scraped off rocky outcrops further north, off Peru. But nowadays potassium nitrate is considered too dangerous to handle, let alone breathe.

Priwall – four-masted barque built by F. Laeisz of Hamburg for the nitrate trade – had steam winches and shore staff

The beautiful four and five- masted barques that set records and made fortunes for A.D. Bordes of Bordeaux and F. Laeisz of Hamburg shifted up to 5,500 tons of nitrates in eleven days flat, but they had steam winches – four to a hatch – and a small army of cadet officers and shore staff. Monkbarns did not.

Monkbarns boy Eugene Bainbridge, rowing around the bay visiting the other ships in Iquique in 1924, wrote enviously: “Priwall, which we went on next, was the antithesis of the Rhone, being spotlessly clean. She had every modern fitting – brace-winches (motor), halliard apparatus for two men to raise the halliards with ease, and a derrick on the jigger. Two wheels amidships with cable connection aft, where there are two more wheels under the poop. The Third Mate showed us the Captain’s saloon, decked up with light polished wood round the walls and carpet on the floor. She also carried plenty of spare spars etc. […] There was a bunk in the chart house for the Old Man, and a crowd of English charts used on the voyage round the Horn. We had a look at the log book, which registered one week nothing but 12 and 14 knots!”

Notwithstanding the rise of the oil industry by the 1920s, Corsar was not alone clinging to canvas in 1895. Many of the names familiar to us from the last days of sail were built after Monkbarns, including Penang and Pamir (both 1905), Peking and Passat (both 1911).

Laeisz had in fact only completed Priwall four years previously, in 1920, having been interrupted by the First World War. (In 1939 she arrived Valparaiso just in time to be trapped by the Second World War. She was interned, and 1941 was donated to the Chileans to avoid her falling into allied hands. Renamed Lautaro, she continued in the trade until she caught fire and burned out in 1945 while loading a cargo of nitrate off Peru.)

View of Valparaiso bay from Naval School. Ships left to right: Peru, Santiago, Monkbarns, Taltal, Queen of Scots (white hull) and Valparaiso in dock. Extreme left: barque California. E. Bainbridge collection

Though most sailing ships were less well equipped than the ships of the Flying P-line, they were still holding their own against steamers on the longer routes, to Chile and Australia, because of the price of coal – and the demand for sail-trained officers that would continue in motor-ships and oil tankers for many years to come.

Boys were cheap, British ships indentured them for four years largely unpaid and by 1919 (following a mutiny aboard) Monkbarns had expanded her deck housing to accommodate a dozen of them. They often made up half the crew. Steamers couldn’t afford to hang around, but sailers could. And hang around they did, for months at a time by the end, waiting for a charter.

Monkbarns left Valparaiso with her last cargo under sail in early 1926: a load of guano salvaged from another victim of Cape Horn, Queen of Scots. After they had sailed, the boys spent several days trimming the ship, wheeling the filthy stuff down the deck from the fore hold to the hatch aft. The ABs had refused, but the boys couldn’t.

As is recorded elsewhere, it was to be a weary voyage; Captain William Davies died – probably of stomach cancer – and they put into Rio, they were becalmed, suffered baffling winds and ran out of food.

They finally arrived in the Thames under tow after 170 days out and anchored off Gravesend, amazed at the sheer volume of traffic, big and small steamers passing in a continuous stream. Fresh meat and veg were delivered aboard and dinner that night was sausages and boiled potatoes.

“I can say that never was a meal so appreciated,” wrote young Bainbridge. The following morning they began heaving up the anchor at about 8.30am, to the shanty Rolling Home followed by Leave Her, Johnny, Leave Her, for the final leg to Charlton Buoys.

“All hands joined in with a will, even the pilot, so that the echo went ringing over the river and a large crowd gathered on the shore to listen,” wrote able seaman Dudley Turner in the fo’c’sle. “The pilot even grabbed a capstan bar and tramped around with us singing In Amsterdam There Lived a Maid.”

It was July 1926, and Monkbarns was the first full-rigged ship to come into the Port of London for eight years, “a wandering and lonely ghost which we may not see again,” wrote The Star. The Times called her “a picture out of the romantic past”.

Chips the ship’s carpenter was more prosaic. “I’ve had six meals since I came ashore 16 hours ago,” he told the Westminster Gazette, “and I’m still hungry.” Monkbarns was to find only one more cargo – Welsh coal, which she delivered under tow, to Norwegian whalers off Corcubion in northern Spain the following March. She finished her life as a coal hulk – the last British full-rigged ship to sail round Cape Horn, according to Alan Villiers (Sea-dogs of To-day, 1932), still bunkering passing steamers into the 1950s.

My last sighting is from a personal letter. Brian Watson, later senior pilot/deputy harbour master at Montrose, was then a nosy British steamship apprentice in the Baron Elibank. In 1954 he spotted a name in raised letters on the nearby bunkering hulk after his ship had sought refuge in Corcubion bay during bad weather. He recognised she was an old Britisher and climbed aboard for a look round.

In 1999 he wrote: “We berthed alongside a coal hulk and I could clearly see her name Monkbarns the metal letters still visible on her counter stern.” He said the masts had been cut down to stumps and he thought the bowsprit had been cut away, most of the deck and poop cabins had been stripped, a rusting galley stove had been moved into the poop accommodation.

Unfortunately, he was spotted by the steamer’s Mate and chased back to work before he could check the bows for the little white horse. The hunt continues for Corsar’s last figurehead with local help. More Watch this space – https://historiasdebarcosyveleros.blogspot.com

© Jay Sivell

This article has been amended since it appeared in The Cape Horner magazine, the journal of the International Association of Cape Horners. August 2014, V2 No 65

Next – Sniffing Stockholm Tar

Previously – In Remembrance: Save our Ships

Written by Jay Sivell

October 8, 2014 at 5:21 pm

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, Uncategorized, WWII

Tagged with apprentice, Cape Horners, first tripper, handelsmarine, John Stewart & Co, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, marina mercante, marine marchande, merchant navy, Monkbarns, Priwall, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, seamen's pay & conditions, square rigger, Tall ships, windjammer

A sailor’s life – 72. Death of a master, 1926. Monkbarns’ last trip

He was the teenage only son of well-to-do parents, with uncalloused hands and a yen for real life. Mother and Father – a marine insurance broker – were off on a world cruise for their health, so they packed him off on one of the last British windjammers.

And that was how Eugene Bainbridge, ex-Marlborough College, joined the motley crowd in the half deck of Monkbarns with his expensive Leica in Newcastle NSW in 1924 and set sail for two years on what would turn out to be the old square-rigger’s very last trip.

Bainbridge père paid £38 for Eugene’s third class berth out on the P&O passenger ship Barrabool – which was nearly five months’ pay for the men in Monkbarns’ fo’c’sle. John Stewart & Co apprentices, of course, as their indenture papers firmly stated, received “NIL”.

But even with half the hands working unpaid, the sums for the old windbags were no longer adding up. One by one, John Stewart’s fleet had been sold for scrap. Monkbarns was among the last four, and she had been laid up in Bruges for over a year until a lucky cargo of rock salt brought her out of retirement in 1923 one more time.

By Christmas 1925, she was in South America, in Chile, and the “boys” in the half deck saw in New Year 1926 stowing half a cargo of guano picked up from a derelict in Valparaiso bay – another old sailer that would never see Europe again.

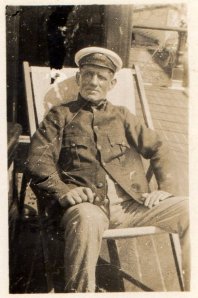

Monkbarns at sea, October 1925 – Captain William Davies, Ian Russell AB at helm and ‘Sails’, Henry Robertson – private collection E. Bainbridge. “The Old Man went below to put on a clean collar”

They left in mid January, bound for home via the rough passage round the Horn. So far the voyage had already claimed two lives since the ship left Liverpool three years earlier – an apprentice lost overboard off one of the yards in a gale and a suicide by morphine overdose in Newcastle NSW – and now the master was dying of stomach cancer, but the seven apprentices didn’t know that.

Two days out of Valparaiso, Eugene wrote in the diary his dad had given him:

“23.1.26 Saturday. Washed half deck with John [Davies]. Took wheel 12-2pm. It struck me again what an advantageous point of view the wheel is. Everything puts on a more pleasing aspect as one views the quarter deck, and shipmates busy with some uninteresting job seem to hold an enviable position. The beautiful silence which reigns as you keep one eye on the weather leech of the top gallant sail. The sea is covered with little ripples today but would otherwise present a flat surface. The breeze is not bad, though considerably less than yesterday and the courses are drawing well. The breeze has dropped again but at 1.30 tonight it suddenly livened up and clouds appeared on the port quarter. Hall [seaman] came on to the lookout and started to talk about the copra trade before the high duties in Sydney. He said that it was on account of one or two fires that high duties were put on, and now there is no trade to speak of, the main bulk going to USA.

“24.1.26 Sunday. Oiled my second pair of oilskins and hung them out to dry. Turned in in the afternoon. Still making westerly and no sign of change.

“25.1.26 Monday. Finished chipping anchor chain and tarred some of it. Very little wind and still going to the westward. A fair wind (NW) is about the last thing that anyone would expect and we shall soon be in Australia like this!

“26.1.26 Tuesday. Wheel 8-10. Nothing to do but watch the sails. Wind gradually dying out and ship starting to roll slightly. Fine day and sun very strong. No clouds about. Wind disappeared and rolling at times. Finished the port anchor chain and lowered it into the locker. Hove starboard chain up on deck ready to scrape. Beautiful evening and Dave [cabin boy] joined me on the lookout from 8-9.30. I told him I wouldn’t be entertaining but he managed to get through a fair amount of talking, as usual, and was evidently satisfied. We discussed Goethe’s Faust, or at least, he did, and then he praised Scarlatti and Chopin.

“27.1.26 Wednesday. Flat calm and very hot (85 degrees in shade). Sleeping on main hatch where the night air is refreshing. Scraped the starboard anchor chain, tarred and stored it. This evening, the mate gave me a bucket to put a new rope handle on. I did it after referring to the book and put the usual “simple Mathew Walker” on. He praised them next day.

“28.1.26 Thursday. Flat calm and water like a sheet of glass. Saw big shark off the side of the ship but it went when we got the hook ready. It did not turn when it came to eat some offal which had been thrown overboard!! Started to trim the cargo in the forehold and taking it in barrow to the after hatch to dump. I had the job of standing by the hatch to tip the barrows. Played Langford [sailor] at chess. Slept out on the main hatch. Heavy dew. There are no apples or peaches in the ship, only prunes!”

For three weeks, as the ship made its way slowly out into the Pacific, the port and starboard watches chipped, tarred and stowed the mooring chains, and trimmed the cargo in the forehold, wheeling the stinking choking stuff barrow by barrow to the after hatch to dump. They reeved off new buntlines, downhauls, clewlines and braces. Chips made new blocks, and Eugene stood his trick at the wheel.

By the first week in February they’d swung SSE with the Easterlies and were heading for the Horn, the sea was becoming heavier and the skies had turned grey.

“6.2.26. The Old Man is bad today, and everything is done to stop the ship from rolling,” Eugene noted. “The mate changed course three times tonight for that reason.” In the half deck, a heavy tin of jam fell out of the apprentices’s locker onto Eugene’s head, inflicting damage.

“8.2.26 Monday. The atmosphere is the dampest that I have ever known and the horizon is blurred with mist. Sea and sky are grey alike and the wind from the northward is fairly strong, bringing with it a heavy swell. It was cold at the wheel at 12 o’clock today… The Old Man was a little better today and enjoyed a joke. The mate is very pale and together with overstrain and overwork has not slept for over 48 hours. No sights have been taken owing to the dullness but the mate took some stars last night. Lookouts are kept night and day and a sharp lookout for ice is to be kept. We are standing by all the time now, ready to attend brace or take in sail. When we were doing about 9-10 knots this afternoon and I was at the wheel a school of large Black Fish was keeping up with us. They jumped a little from the crests of the waves and could be seen black beneath the surface quite close. I should guess 12-14 feet would be their length and they had fairly pointed noses and a big thick dorsal fin.”

The temperature fell, day by day. “10.2.26. Wednesday. The temperature today was 45 degrees but it appeared to be much colder aloft and the steel yards stung when gripped. The old man is much better and cracking jokes.”

As they got closer to the Horn, lookouts were posted day and night. They were racketing along at 12 knots, a hell of a speed to hit an iceberg. “Boiled some pitch for the Mate this evening to do the chartroom deckhead. The chartroom and in fact the whole poop is leaking. The heavy sea having strained the seams aft. The two Johns relieve each other and, with the time-keeper, watch over the old man at night. He is not so well tonight. We should round the Horn tomorrow with a fair breeze.”

The Horn was passed in thick mist, shortened down to topsails only, and with their eyes peeled for icebergs. Jock Scott warned Eugene to go to bed fully clothed, “to be ready if anything should happen, so we did.”

Monkbarns half deck. Eugene (right) and John Davies. Jim Holmes in bunk. Private collection E. Bainbridge

The temperature was 6°C (44° F), mild. There were albatross, mollyhawks, stormy and great petrels, and even a penguin around the ship. (“Sails revealed they are always met with down in the South Pacific and Atlantic, and sometimes hundreds of miles from land! This one was a dark brownish grey with a bright yellow streak across the eye. He was up an down after fish and squeaked not unlike the flapping topmast staysail.”)

Once past the Horn, the weather cleared. The ship “steered like a bird, with three spokes either way”, wrote Eugene ecstatically. There were four pairs of albatross following the ship, and a school of Cape Horn white-bellied and white tailed porpoises. Their breathing under the bows made Eugene realise he was not alone on his lookout. He saw and heard several whales. ” The Old Man is much better and has taken to growling at his nurses again in the old style. He has told the mate not to call anywhere or even stop a ship, if sighted. He is certainly an optimist. The position is about 54S 56W”

By the end of the month, it was 70° in the shade and the wind had dropped to 2 knots. The Old Man was being nursed day and night, injected rectally with milk and brandy because he could no longer keep any food down. One apprentice from each watch was set to watch over him. Eugene complained that his friend Jean Seron had been banned from studying navigation in the master’s quarters – a light novel was less distracting. “What hard luck as he never gets a chance to study now, wasting every watch in the Old Man’s room doing nothing. He wants to go for his ticket at the end of the voyage…”

Eugene was not posted to the sickroom. Instead, he was kept busy painting, or bending on sails. Off watch, he sketched, fished for sharks and worked on his model of the ship. The food was now also running low. “Traditional, for a sailing ship,” wrote Eugene. “Grub seems very scarce and uninteresting; beans every day, everywhere substitutes.” They caught and ate a dolphin, boiling the meat for tea. “The cook made a very bad job of it.”

The Mate was at his wits’ end. He’d decided to countermand the master’s orders and head for Rio, or Bahia – whatever port they could reach with the prevailing wind and currents. The Old Man was dying. But by the middle of the month they were still 900 miles from Rio and the ship was becalmed. The weather grew hotter and hotter. The Old Man could no longer bear any noise. Singing was banned, and the accordion. It was 90°F (33C). The Mate rigged a funnel from the skylight to Captain Davies’ bedside, made “of weather cloth and and bucket hoops.”

But the ship still had to be worked. One of the senior apprentices, Raymond Baise, was promoted to acting 3rd Mate. The 2nd, Mr Williams, who had started the voyage as able seaman, took over many of his chief’s tasks and watch after watch they braced the yards, tacking, wearing ship – trying to catch the slightest breath of wind, while the exhausted Mate kept his eye on all, scouring the Ship Master’s Medical Guide for instructions on how to ease the dying man.

They sighted land (Cape Frio) on the 25th of March.

“26.3.26 Friday. Wore ship every watch and made scarcely any ground through doing so. All the courses are of course hauled up to make the handling of the yards easier. Cape Frio was in sight all the time during the day and the light was clearly visible during the night. Several steamers passed the lighthouse and cape during my lookout, and I reported their lights in turn as they came in view. The wind dropped and there was a dead calm before morning. All the ground we made was done in crab-fashion and owing to the Great Brazilian Current, which drifts southward. The wind is a dead muzzler from the west and the ship’s head (steering compass) is S by W on one tack and NW by N on the other.”

On the 28th they sighted the Sugar Loaf, and by evening the Old Man had been taken off to hospital. The 29th, Eugene whizzed through his chores (cleaning brasswork, washing down the decks, getting a sail up out of the locker through the choking ammonia fumes) and tried to go ashore in the launch at 5pm as the Mate arrived back from the hospital. The Mate said “no”, Rio was under martial law.

The following day he tried again, but the Mate didn’t want to share the launch with him. “He saw me coming and had his answer ready, which was that I could not go in the launch with him as it cost money. I asked him how much it would be and he said that he did not know and that anyway he had too many worries to be bothered with people going ashore for pleasure […] He left the ship at 8.30 with the two Johns and I remained on deck gesticulating and whistling to every launch and bum-boat that appeared within hailing distance.”

By 10.20am Eugene was ashore, taking tea and refreshments in the Alvear Cafe on the Rua Rio Branco, before strolling on past the Municipal Theatre, (“very like the Opera House in Paris”) and the Senate. He took a tram part way up the Corcovado, but found there was a two-hour wait for the next train to the top – where the famous Christ the Redeemer statue was still only a pile of bricks. Instead, he marvelled at the lizards, a spider the size of his hand and three people with long nets catching six-inch blue butterflies (“They make beautiful ash-trays”). After that he caught a taxi and went to the Botanical Gardens, where he admired the famous avenue of 100 palms, and then treated himself to an icecream soda before returning to the ship in a bum-boat under its own sail, for 10 Milreis (about 6 shillings, or a day’s pay for a sailor). “And arrived back five minutes before the Mate. There was a loud shout from all hands as I hove in sight.”

Captain William Davies died in the night, aged 61. The telegram to his wife with the first indication that he was ill followed the next day by a second, with the shocking news of his death.

All the apprentices and “Sails”, Henry Robertson, were invited to the brief funeral in Rio’s English cemetery, but there is no description of it in Eugene’s diaries. Only six of them were needed to collect the body from the hospital. Eugene, left to kick his heels in the agent’s office for an hour with Bill and old Sails, recognised a passing Old Marlburian by his school tie, and struck up a chat.

Monkbarns left Rio the following morning in dripping rain and thick cloud under a new Captain Davies, the former 1st Mate, waved off by the agent’s clerk, Eugene’s old school crony Sharpes, who came aboard for a fine display of shantying up the anchor. “An appreciative audience makes a world of difference and I have never heard shanties sung so well aboard the ship,” wrote Eugene. “Bill and Mac supplied most of the solos and the choruses were all hearty.”

The new master was determined to keep spirits up. They were bound for home – across the Line.

…

For the further adventures of Eugene Bainbridge esq.– supported by the newly discovered letters of Raymond Baise (!!) – find me a publisher.

Next – In Remembrance: Save our Ships

Previously – A small man, tubby

Written by Jay Sivell

October 8, 2012 at 11:45 am

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Other stories, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice

Tagged with apprentice, Barrabool, Bert Sivell, Cape Horn, Captain Richard Davies, Captain William Davies, death at sea, eating dolphin, Eugene Bainbridge, first tripper, guano, handelsmarine, historic ship photographs, icebergs, Jean Baptiste Seron, John Stewart & Co, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, marina mercante, marine marchande, Marlborough College, merchant navy, old school tie, Raymond Baise, Rio de Janeiro 1926, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, seamen's pay & conditions, square rigger, Tall ships, Valparaiso, Whales, windjammer

A sailor’s life – 56. Wives on wharves

“I often get a yarn with the ‘old man’ on the same old topic – marriage. His chief argument is that marriage is no good for a man going to sea, because he is seldom home. He says it is only keeping another man’s daughter, but I argue what could be better than for a man to come home from a voyage and find his wife waiting with outstretched arms to greet him, because if a girl really loves a man she is willing to put up with her man being at sea most of his time and will make the most of him while he is home. Am I not right, darling?”

Bert Sivell to Ena Whittington, December 1919

The “old man’s” view of women was jaundiced. Captain McDermid – all of 35 – had been engaged once himself, he told Bert during their first trip with the Shell oil tanker Donax. But his girl had spent her last penny to get a fur coat. When he saw that he turned her down, he said, because if she would spend her own money like that, what would she be like with his?

But McDermid’s bark was worse than his bite. Though unmarried himself, he was happy to wire ahead so that the 2nd Engineer’s wife could be waiting on the pier head as the ship came alongside in Shellhaven on their return from the Baltic, and three days later when the tug took her and the chief engineer’s wife off again as Donax left for the States, he had three long blasts blown on the ship’s whistle as a farewell to the ladies. (“The tug replied by giving a series of blasts, trying to make Hip Hip Hurrah, so the wives had a good send off. There were four British steamers lying at anchor there and I expect they wondered what had gone wrong.”)

In a “home” port, like Shellhaven in the Thames estuary, Shell’s married officers – and married officers only – were permitted to have their wives living aboard with them. “They have to pay their own expenses, but the firm makes all the arrangements, which is very good of them,” Bert wrote, enviously.

He himself managed only snatched evenings on a sofa at Ena’s digs in Tunbridge Wells, arriving at 6pm and running for the 10.10pm train for Charing Cross, Tilbury, and a midnight walk back to the ship. Once he managed a trip to his parents on the Isle of Wight. Donax had arrived at Thameshaven at 2pm, they were tied up by 5pm, he’d hailed a tug to Gravesend, and run for the ferry to Tilbury just in time to catch the London train. He had got to Ryde as the clocks were chiming 3.3oam.

Small wonder he was envious of married colleagues. ” Here is another chance you have missed,” he wrote in April 1920. “You could have met the ship yesterday afternoon and stayed on board until tomorrow morning. A little spell like that about twice every two months and the drydocking every six months will not make married life so bad after all, eh! sweetheart, and there is always the prospect of the three months furlough.”

London docklands, undated – not always a comfy spot for the wives to hang around, waiting for their husband’s ship

The cranky former RFA Oakol, latterly the Shell oil tanker Orthis, to which he was transferred that May offered even more opportunity for the men to see their wives (“… The 2nd mate’s wife was aboard almost before the anchor was down…”) due to the time she spent in Millwall dock and Shellhaven while the engineers struggled with her engines. Bert managed many more trips to Tunbridge Wells after work, and several to Ryde – taking Ena with him on the night train.

“It will be a taste of what is in store for you in future, dearest, when we are married and you have to suddenly fly off to Glasgow or somewhere else on receipt of a wire. You will get quite used to night travelling.”

Captain Harding had his own wife aboard Orthis as often as possible and was generous with time off for his unwed chief officer. The likelihood of transfer “out East” hung over them all, if not to Palau Bukom in the Singapore Straits, where the Shell group had historic concessions, then at least to Batoum on the Black Sea, where a pipeline delivered oil from the Anglo-Persian’s newly acquired Caspian wells. The cosy brief domesticity in Shellhaven or even Millwall or Rotterdam was a rare interlude, to be grabbed with both hands, spurred by the arrival of charts for Batoum that May.

When the company tried to ban wives, the men were outraged. “There is a new ruling coming out in the firm that no wives are to be allowed on a vessel with benzine in,” Bert reported. “Some fanatic, I suppose, thinks it dangerous, but I have an idea that rule will be broken a few times or many will leave the firm.”

And they cheered the master of a Belgian time-charter ship who let go from the wharf and anchored in the stream when ordered to put his wife ashore while loading. “The installation manager was aboard within an hour, asking him to resume and saying his wife could stay.”

Time snatched with husbands aboard oil tankers was not an unmixed blessing, at least for the wives. “They have been trying to kill us all just lately here by letting go a lot of gas,” wrote Bert from Shellhaven in August. “They purify petrol by passing some acid through it. This acid is then run into the sea and the end of the pipeline is not far from us. They run this stuff away in the middle of the night and the ‘sniff’ is thick enough to cut. Nearly all the Europeans on board are bad through it. Last night it nearly turned me up and I have been queer all day.”

Summoned by telegrams, expected to park children and leap onto trains at little or no notice, and then kick their heels on wharves in strange ports until someone had time to pick them up, the lot of a merchant officer’s wife was not as simple as it had been in the days of sail. Then, each ship was a small business venture, and it was common for a master to own a part share. Property ashore was idle money, so many captains simply took their wives with them – resulting in children born and raised at sea. As late as the 1920s, there were still wives in sail.

When Bert Sivell joined his third Shell oil tanker, Mytilus, in Rotterdam shortly before Christmas 1920, Captain Jackson had both his wife and his little daughter living on board. Bert couldn’t wait to be married himself.

Read on: The wife’s tale II

Previously: A trip to Dublin, September 1920

Written by Jay Sivell

January 26, 2011 at 5:14 pm

Posted in 3. Shell years - 1919-1939, Historical postcards, Other stories, Seafarers' wives, Shell oil tankers

Tagged with Anglo-Saxon Petroleum Company, Bert Sivell, Donax, handelsmarine, Isle of Wight & Sivell family, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, marina mercante, marine marchande, merchant navy, Mytilus, oil tankers - Shell, Orthis, Sailing ship apprentice, seamen's pay & conditions, seamen's wives, Shell oil tankers, Shell tankers, Shellhaven, Tall ships, windjammer

A sailor’s life – 46. Through a glass, darkly

It was an undated newspaper cutting among my grandmother’s papers, clipped out and saved long after Bert Sivell’s death. A bit of yellowing ephemera laid by for the oil tanker husband who never came back: “On show in the Master Mariners’ Club for the next week or so – a magnificent scale model of the full rigged ship Monkbarns.”

The 21-inch model, “hand carved with authentic teak rail and working blocks”, had been made by a Trinity House pilot for a colleague who had served his apprenticeship in the old windjammer in the final years, by then one of a big crowd of teenage boys in the half deck. I could imagine the two old salts with their heads together, jealously overseeing and lovingly recreating every last detail: the tiny extended boys’ house abaft the main hatch, the little flying horse under the bowsprit, the chart house on the poop that would have been welcome too in the stormy watches when Bert was minding the sails.

The little ship is perfect. Dustless and frozen in time, all sail spread and a bone in her teeth – tantalisingly beyond touch in her glass case in the sunny room in a private house when I finally traced her. Sea Breezes had again provided the answers. A letter dropped casually on the mat: “We’ve got her, come and see.”

This is no museum piece. She belongs to a real seafaring family, to sons and grandsons themselves once deep-sea sailors. Part of their lives. A hand-carved homage to a world now hull down over the horizon.

Read on: In remembrance

Previously: Boy’s own story

Work in progress: the book I never wrote about the sailor grandfather I never knew, from his apprenticeship on the square-rigger Monkbarns to his death by U97, presumed lost with all hands aboard the Shell oil tanker Chama in 1941 Blogroll

Written by Jay Sivell

November 14, 2010 at 12:39 pm

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice

Tagged with apprentice, Chama, handelsmarine, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, marina mercante, marine marchande, merchant navy, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, square rigger, Tall ships, windjammer

A sailor’s life – 45. A boy’s own story

Nothing much seemed to have changed when Monkbarns limped back into Newcastle NSW in November 1920 with a new captain and a broken mast.

The Monkbarns boys were given the afternoon off to hear a concert at the Mission, and for most of the next month they had time off in the evenings and at weekends to lounge about the beach, surfing, playing tennis and making up tea parties, while they waited for the repairs. Captain Davies of Nefyn was welcomed like long-lost son by Newcastle’s Welsh mayor, Mr Morgan, and there were “umpteen” other sailing ships in port, including Vimeira, Garthsnaid, Kirkcudbrightshire and Rona (- now possibly better known as Polly Woodside), with 37 apprentices between them. On November 5th and 6th apprentice Francis Kirk wrote just two words lengthways down an entire page of the schoolboy notes he kept that trip: “Enjoying life”.

On the 20th Monkbarns hosted a dance, with more than fifty girls, he recorded happily. The old ship looked fine, decked out with flags and Chinese lanterns, and “our famous jazz orchestra” had played selections during the evening. They were still in Australia at Christmas, which Kirk celebrated in Lambton with the Blanch family, and they saw New Year in with a big regatta in the harbour at which the Monkbarns “men” won £5 in one of the races. On January 9th 1921, they left Newcastle again bound for South America, “with heavy and breaking hearts”, Kirk scrawled, “All the girls gathered on Nobby’s Head and waved the old ship out of sight…”

Kirk, like Bert Sivell, had eventually left sailing ships for oil tankers, but he had never got over his love of the old square-rigger.

In 1957 he became one of the first members of the new British branch of the Amicale Internationale des Capitaines au Long Cours Cap Horniers – or Cape Horners’ Association – originally founded in St Malo, France, in 1937 to “promote and strengthen the ties of comradeship which bind together the unique body of men and women who enjoy the distinction of having voyaged round Cape Horn under sail”. They were “albatrosses” (who had commanded a sailing vessel round Cape Horn), “mollyhawks” (served in a sailing vessel round Cape Horn and subsequently commanded a motor ship), or “cape pigeons” (cooks, stewards, passengers etc).

Kirk – ranked Mollyhawk – threw himself with gusto into the annual jaunts to St Malo or Hamburg, Oslo or later Mariehamn, which held the record for old Cape Horners. “He used to come back with pictures of him and ‘old so-and-so’ and usually a woman in the shot whom he would pass off as such-and-such’s wife,” said his son. After his death there had been several intriguing lady callers.

In the 1960s an English language journal was set up, The Cape Horner, and its editor, Captain AG Course – UK member 9, wrote that if any member was in Bournemouth, they were welcome to join the members’ coffee mornings, every Friday at 10.30am in Bealson’s cafe on Commercial Road. “No advance notice is necessary and your wives, relatives and friends will be welcome. Only one wife at a time, please!”

The maritime author Alan Villiers wrote of joining one of these coffee mornings in 1971, and meeting “eight wonderful old boys, most of them octogenarians, except one aged 92, all with the stamp of the sea still upon their open faces, the snap of command in the old blue eyes”. The “wonderful old boys” more generally were not uniformly impressed by the new boys’ patronage (“… not really a proper sailor…”), and the subsequent acceptance of yachtsmen as Cape Horners when anno domini began to tell on the original pre-motor, pre-GPS membership was contentious.

I was too late to meet Francis Kirk, or Harry Fountain, Victor Fall, Lewis Watkins, Lionel Walker and “Algie” Course – who single-handedly salvaged most of what is known of Monkbarns’ history, mainly by running his finger down the UK Cape Horners’ membership list and calling the old shipmates in for a fireside chat. (Which accounts for some of the more lurid tales). But their lives still resonate down the generations in remembered stories (“He said the freezing flailing canvas ripped fingernails to the quick…” “you tapped the biscuit on the table to knock the weevils out…”), and dusty diaries and yellowing photos, providing a lasting testament to all those boys like my grandfather who went down to the sea in ships and did business in great waters in the last days of sail.

Coming next: A model ship

Previously: Goodbye, Monkbarns – Corcubion, 1954

*

Sea Fever

I must go down to the seas again, to the lonely sea and the sky,

And all I ask is a tall ship and a star to steer her by,

And the wheel’s kick and the wind’s song and the white sail’s shaking,

And a grey mist on the sea’s face and a grey dawn breaking.

I must go down to the seas again, for the call of the running tide

Is a wild call and a clear call that may not be denied;

And all I ask is a windy day with the white clouds flying,

And the flung spray and the blown spume, and the sea-gulls crying.

I must go down to the seas again, to the vagrant gypsy life,

To the gull’s way and the whale’s way where the wind’s like a whetted knife;

And all I ask is a merry yarn from a laughing fellow-rover,

And quiet sleep and a sweet dream when the long trick’s over.

John Masefield 1902

Written by Jay Sivell

November 4, 2010 at 3:03 pm

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice

Tagged with AG Course, Alan Villiers, apprentice, Bert Sivell, Cape Horners' Association, Garthsnaid, handelsmarine, Harry Fountain, John Masefield, John Stewart & Co, Kirkcudbrightshire, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, Lionel Walker, marina mercante, marine marchande, merchant navy, Newcastle NSW, Polly Woodside, Rona, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, Sea Fever poem, square rigger, Tall ships, Victor Fall, Vimeira, windjammer

A sailor’s life – 44. Goodbye, Monkbarns

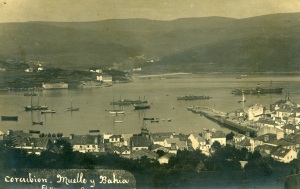

Monkbarns' last reported anchorage - off Corcubión, northern Spain. View of the bay: Museo Maritimo Seno de Corcubion

In 1954 a nosy British steam ship apprentice spotted the name “Monkbarns” in rusty raised letters on an old coal hulk in Corcubión, in northern Spain, and clambered aboard.

There wasn’t much left of Charles W. Corsar’s fine teak fittings, the old seaman recalled years later, in response to an appeal in Sea Breezes. Where the saloon had been aft, there was just a stripped out space with a few doors and an old cast-iron stove in the corner. The tall masts were long gone, chopped down to stumps in 1927 when the old sailing ship was sold for £2,500 to Bruun & Von der Lippé of Tønsberg, Norway, for one of their several whaling stations in Galicia. He did not have time to see if the little flying horse figurehead was still there before he was chased back to work by a harassed mate, (“though perhaps I visited the cabin in which your grandfather had lived,” he wrote).

*

By June 1919, when Monkbarns docked back in Cork with a cargo of South African maize, she had been away from Europe for nearly two and half years. The war was over, and she had survived – unlike 263 other British merchant sailing ships. John Stewart’s fleet had numbered ten fine ships in 1914. By 1919 Monkbarns was one of four left.

That summer, Captain James Donaldson “swallowed the anchor” and retired from the sea. The 24-year-old Mate, who had first set foot aboard Monkbarns in Hamburg as a callow apprentice of sixteen, was also leaving the ship: bound for his parents’ home on the Isle of Wight and the daily commute to college in Southampton, to sit his exams and (he hoped) graduate to Master.

Bert Sivell had served Donaldson as man and boy for eight years, through war and storms and even mutiny, but the old Scot – never effusive – wrote only: “This is to certify that Mr Hubert S. Sivell was promoted 1st Mate of the above named ship at Melbourne, about beginning of March 1918, to about beginning of June 1919. During that time we had a crew of the most difficult men to work. They started insubordination before leaving Hobson’s Bay, continued and was so bad that the ship had to put into Rio damaged for want of men to work the yards etc. and continued right on to end of voyage. But through it all Mr Sivell was attentive, obedient, and strictly sober.”

And that was that.

Captain Donaldson was seventy, and had been at sea since he was fourteen. He retired to Australia, where he and the patient wife his apprentices never mentioned eventually settled in Bunbury near the eldest of their five children. Captain James Donaldson jnr was appointed pilot to the burgeoning timber port there in 1921, and was to rise to harbour master in a long and successful career ashore. In 1925 old man Donaldson’s details appear on a manifest for the White Star liner Medic arriving at Southampton, England, but his name is struck out. His great grandson believes he died in Scotland. Elizabeth King Donaldson continued to appear on the census for Bunbury with her son’s family until 1931, when she would have been 77.

Monkbarns’ last master, Captain William Davies of Nefyn, north-west Wales, died of stomach cancer in Rio on March 29, 1926, during a final and ultimately fruitless attempt to make the old ship pay. During the slump of 1921 she had spent 16 rather jolly months laid up in Bruges, with regular visits from the captain’s family and only old Henry Robertson, the sailmaker, for crew – “Sails” declaiming Scott’s epic Marmion to himself as he stitched away in his sail locker, or rattled pots in the galley. But Captain Davies didn’t survive the last voyage and the ship was brought home by the Mate, his nephew Richard Davies.

When Monkbarns finally moored at Charlton buoys on 10th July, hungry and a month overdue, to a chorus of whistles from the steamers she passed on her way up the Thames, even the Times wrote up her arrival as “a picture out of the romantic past”. But despite three years and four months away, the voyage had been so unprofitable that the remaining partner of John Stewart & Co decided he could no longer keep the vessel on.

On March 5, 1927, Monkbarns left the UK on her very last passage, bound for Corcubión, Spain, with a consignment of Welsh coal – supposedly for the Norwegian-run whale boilers of the Compañía Ballenera Española.

Records show the Norwegians caught 242 whales off Spain that year – producing 7,000 barrels of oil. But already the great teeming canyons beneath the Bay of Biscay and the straits of Gibraltar were being hunted to extinction. Too many licences had been granted. They had averaged 35,000 barrels in each of the previous four years. Now fossil oil was on the march.

The Norwegians say Svend Foyn Bruun & Anton von der Lippe shut down what they called their operation in Corcubión in 1927 and decamped to Newfoundland, taking their boilers with them. But Spanish records do not show there was ever a whaling station in Corcubión, just a coking plant: the Compañía General de Carbones.

Street art in a derelict former whaling factory in Galicia, awaiting demolition for a shopping mall - photo by Peri from ekosystem.com

There were whalers further along the beach at Caneliñas – but not until 1928, the year John Stewart & Co sent their last ship, William Mitchell – the very the last remaining British-registered commercial full rigged ship – to the breaker’s yards. (Garthpool, the other contender for “last British-flagged sailing ship” was in fact registered to Montreal when she was wrecked off Cape Verde in 1929, although confusingly she still flew the Red Ensign…)

Grimy, rusting, forgotten, somehow Monkbarns hung on. She is not listed among the known coal hulks of the Compañía General de Carbones anchored in the bay at Corcubión at that time (Burdeos, Mayagüez, Maria Luisa, and Sorrento) yet when the whaling station at Caneliñas reopened in 1952, she was evidently still there. Reduced to coaling weather-bound steamers, but still afloat according to that nosy British apprentice.

By then, both Bert Sivell and Captain James Donaldson were long dead. Monkbarns had outlived them both.

Read on: Boy’s own story

Previously: Man overboard – the death of Laurence O’Keeffe

Written by Jay Sivell

October 3, 2010 at 12:34 pm

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Historical postcards, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, WWI

Tagged with apprentice, Bert Sivell, Bruun Von der Lippe, Bunbury, Canelinas, Captain James Donaldson, Captain William Davies, Charles W. Corsar, Corcubion, Garthpool, handelsmarine, John Stewart & Co, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, marina mercante, marine marchande, merchant navy, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, square rigger, Tall ships, war at sea, Western Australia, whaling, William Mitchell, windjammer

A sailor’s life – 43. Man overboard

“Looks like we’re going to get wet,” shouted ordinary seaman Laurence O’Keeffe over the storm, as Monkbarns’s poop vanished under a mountainous green sea. They were his last words.

The jib-boom to which O’Keeffe and apprentice Lewis Watkins were clinging rose up and up, until they could see underside of the old sailing ship for half its length below them. Then the ship’s head came back down with terrific force, “plunging the boom and the men clinging to it into a mighty mass of rushing water,” according to a fellow apprentice, Victor Fall. The jib-boom was buried. As the water poured away at the next rise of the bows, Watkins emerged, caught head down in the jib-boom guy, but O’Keeffe, further out along the foot rope, was gone, ripped from his handhold and sucked into the sea. All Watkins remembered was being forced upwards by a great pressure of water.

Captain Donaldson refused to lower a life boat.

“The sea was incredibly savage and confused,” Fall remembered, “with enormous swells rising up to a great height, toppling over in a fury of foam, while the fierce wind whipped an unending spray from the crests. No [life] boat could live in such a sea, an attempt would mean not only the loss of one man, but that of a whole boat’s crew.”

Bert Sivell, the mate, threw a lifebelt from the poop in a final, helpless gesture. But they all knew it would do no good. “The ship raced on through the storm,” recalled Fall, “while a fine young seaman drowned astern; nothing could be done.”

It was January 18, 1919, and they were off the coast of Africa, fighting towards Cape Town with a cargo of Jarrah wood railway sleepers.

They had celebrated Christmas in the tropics off Madagascar with a blow-out meal of roast chicken – one between three – which the Old Man, Captain James Donaldson, had laid on in Bunbury, Western Australia, although the Mate, Mr Sivell, marred it slightly by making them spend Christmas Eve tarring down the rigging. There was plum duff and a slightly surprisingly good concert on the foredeck.

Day after day had passed without incident. As they slipped into the Mozambique channel, planning to run down the Agulhas current to the cape, winds and work remained light. They sighted steamers, and flying fish and even a six-foot turtle, gliding lazily through the crystal blue water. By New Year they were clear of the southern tip of Madagascar, but now the weather began to change. One night a sudden fierce squall “nearly caught the ship aback,” records Fall. The outer jib and both fore and main top gallants were carried away. All hands were summoned on deck, to hurriedly lower the yards and reduce sail. Early next morning the remaining rags of canvas had to be taken down and new sails bent on.

It was to be the start of three terrible weeks.

By the time they were on a latitude with Durban, the wind had reached almost hurricane force. They were sailing under reefed foresail and lower topsails only, but the seas were huge. “Great walls of water rushed at the ship, which reared up on the crests, to plunge a moment later, down, down and down into the troughs, and rise again to the next incoming monster,” wrote Fall. At each descent the green torrents swept the foc’sle head as the ship thrust jib-boom first into the next wave.

Shortly before 5.30pm on January 18th, the mate asked for volunteers. The inner jib was still set, and pulling. Someone had to climb out along the jib boom to take it in. A dangerous job. Watkins and O’Keeffe stepped forward.

Watkins was barefoot, wearing only a singlet and an old pair of white trousers, as the order “All hands on deck” had come in his watch below and he hadn’t had time to dress. It saved his life. O’Keeffe was in heavy sea boots and oilskins. He did not stand a chance.

He was only 18. A Welsh boy from Port Talbot, he had been with Monkbarns since she had sailed from Cardiff two years previously, remaining loyal, even during the mutiny of the fo’c’sle hands round Cape Horn the previous summer. In the crew agreement the words “shipwrecked” appear beside his name, and the money due to his widowed mother for this short, tragic career – £38 13s 3d.

He only earned £5 a month, but half of that – £2 10s – was paid to the family at home every month. From now on, they would struggle.

Gloom settled over the ship the evening he was lost. In fo’c’sle and half deck, men were subdued, Fall recorded. But the sea hadn’t finished with them yet. All that night and the next day the gale howled and screamed, and boiling, churning seas swept the decks from rail to rail, making it hazardous to relieve the man at the wheel. It was a week before they sighted land again, and almost immediately another gale struck.

This time the main top’sle carried away, leaving a broken chain lashing lethally around the deck, and while they struggled to secure it, a huge sea poured into the ship, smashing the galley door and washing the Egyptian cook out into the scuppers. The terrified man fled forward and locked himself into his cabin, where for three days he refused to come out.

The galley fire was drowned. Pots and pans were strewn around the ship. But they had to eat, and apprentice Fall was detailed to sort something out. Many years later, he still remembered the stew he’d put together that night. “Everything went into it – salt beef, salt pork, bully [tinned] beef, beans, peas, dried vegetables – everything; but by the cold wet and exhausted crew, including the skipper and mates, it was voted delicious.”

On February 6, 1919, Monkbarns dropped anchor in Table Bay, Cape Town – 63 days from Bunbury, WA. The following day the hatches were opened and the process of unloading began again. Another cargo had arrived.

Coming next: Goodbye, Monkbarns

Previously: Shanghaied

PS A relative of O’Keeffe’s writes from Australia, 10 November 2010: “Laurence O’Keeffe was my late husband’s uncle. He was named Laurence after him. We knew that he had been drowned but until I found your website & story never knew how or when. I couldn’t find a death record for him, but I have now located it on the Deaths at Sea index. A passenger list from Callao, Peru, to Liverpool for the RMS Otega in December 1916 shows several seamen embarking at Coronel in Chile for Liverpool, including Laurence O’Keeffe as a 15-year-old OS of 20 Bute Street, Cardiff, which is where his widowed mother ran a boarding house. It must have been a very tough life in those days.”

Laurence O’Keeffe, then still only 15, was listed by the Pacific Steam Navigation Co. as one of six “Distressed British Seamen” repatriated back to the UK in 3rd class just before Christmas 1916. His previous ship, the four-masted barque Canowie, had been wrecked off Piritu Point, Chiloe Island, in southern Chile, that October. He signed on with Monkbarns on 30th January 1917, just over a month after getting home. It is conceivable he only ever made two voyages in his short life.

Written by Jay Sivell

September 10, 2010 at 11:08 am

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice

Tagged with Bert Sivell, Canowie, Cape Town, Captain James Donaldson, death at sea, handelsmarine, John Stewart & Co, koopvaardij, last days of sail, Laurence O'Keeffe, life at sea, marina mercante, merchant navy, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, shipwreck, square rigger, Tall ships, Victor Fall, windjammer

A sailor’s life – 42. Shanghaied