Posts Tagged ‘Tall ships’

A sailor’s life – 83. Foaming water, clean living

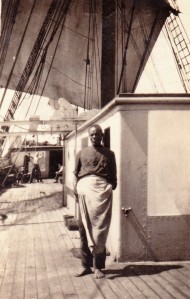

Scantily-clad crew aboard Monkbarns, 1926 – “It then proceeded to rain in torrents and all hands could be seen on deck with next to nothing on, washing clothes. A great day for the sailor’s gear,” Eugene Bainbridge, 6 May (courtesy estate of Eugene Bainbridge)

Descriptions of rounding Cape Horn in sail tend to dwell on ice and howling winds and split fingers and harrowing near-misses. The doldrums, through which ships from Europe must pass to get to the southern hemisphere, feature only as a spot where vessels languish becalmed. The very word has drifted into the English language meaning “inertia, apathy, listlessness, malaise, boredom, tedium or ennui”.

The sheer hard work – and the sailor’s rare luxury of washing himself and his smalls in unlimited fresh water during rain showers in the doldrums – is therefore usually overlooked. This charming reminiscence about life on the German four-masted barque Peking on the Chilean nitrate run in 1928 comes from former Laeisz Flying P-line master Hermann Piening, one of many “grand old boys” interviewed by Alan Villiers, (quoted in The War With Cape Horn):

… And then the trades! That remembered paradise of the ocean sailing-vessel life when all the hardships are forgotten. Through the blue sea the keen cutwater of the sleek, big Peking rips day after beautiful day, scaring the wide-eyed flying fish with the roll of foaming water that forever races at her bow. Here the sailor may feel the essence of harmonious beauty between his ship and the sea. But nothing lasts. The doldrums come with their nervous cat’s-paws of fleeting airs, their sudden swift squalls, their deluge after deluge of almost solid rain.

“You are not to think that we are dealing here with a domain of absolute lack of wind,” says Piening. “That seldom exists, for even slight variations in pressure must always result in movements of air. But the wind is uncertain and faint here. The navigator who is not continually ready to make use of even the lightest breath can spend weeks in this uncomfortable hothouse. There is no rest for the sailors. There are watches in which they hardly get off the braces for ten minutes.

… “There is only one pleasant thing about this region: it rains frequently. In a compact mass, the water falls from the blue-grey sky. Everything and everyone aboard revels in soap and water, for the fresh-water store of a sailer is limited and the duration of the passage most uncertain. A sort of madness seizes everyone. Clad only in a cake of soap, the whole crew leaps around and lets itself be washed clean by the lukewarm ablution. Filled with envy, the helmsman looks at the laughing foam-snowmen into which his comrades have transformed themselves. Everyone pulls out whatever he can wash and lets the sea salt get rinsed out thoroughly. By night the heavy lightning flashes of this region present a splendid show. Often the heavens flame copper-red and sulphur-yellows, and hardly for a second is the vessel surrounded by complete darkness. At times St Elmo’s lights dance upon the yardarms.”

[Editor’s note: The Laeisz four-master Peking is back in Europe after languishing rather unloved in New York for four decades. Yay! A major operation to get her back across the Atlantic in a floating dock last year is now being followed by a major refurb in Wewelsfleth, north of Hamburg.]

Alan Villiers talking to Captain Hermann Piening, ex Laeisz “flying P-line”, from The War with Cape Horn (1971)

Written by Jay Sivell

August 18, 2018 at 2:45 pm

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Other stories, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, Uncategorized

Tagged with Alan Villiers, apprentice, Chilean nitrates, Doldrums, Eugene Bainbridge, F Laeisz, four-masted barque, fresh water at sea, handelsmarine, Hermann Piening, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, marina mercante, marine marchande, merchant navy, Peking, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, seamen's pay & conditions, square rigger, Tall ships, windjammer

Lost at Sea – 82. The sailmaker’s tale

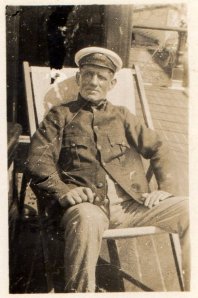

Monkbarns at sea, October 1925 – the Old Man (Captain William Davies), Ian Russell AB at helm and ‘Sails’ Robertson, private collection E. Bainbridge

One of the rare surviving photos of everyday life aboard Monkbarns shows a handsome man in a cap and leather waistcoat sitting on a low bench on the aft deck surrounded by folds and billows of canvas. His tools and twine are laid out in a neat “housewife” beside him, and both hands are busy as “Sails” looks up from his work to smile at the camera.

The master perches on the saloon skylight nearby in jacket and bow tie, having insisted on changing into his good shore-going gear for the occasion. In the background, a youth at the wheel studiously minds the sails overhead. The sea is calm and the sun is high.

Henry Robertson was 70 when the image was recorded in 1925 by the ship’s final English apprentice, Eugene Bainbridge, who brought a fresh eye and a Leica aboard with him.

“Sails” was a grizzled widower from the east coast of Scotland. He liked his own company and staring into the middle distance with his pipe, the master’s son recalled*, and would recite chunks of Sir Walter Scott’s epic poem Marmion to himself whenever he thought no one was listening.

He had been at sea all his life, the son of the court clerk of Montrose who’d died when he was six, leaving the family to experience “what it was like to have the sheriff officer in the house to take away the clock to pay for poor rates,” as he put it.

Back in Scotland were four grownup children, three daughters and a son, born at five year intervals to the pretty housemaid he’d met at a dance in Montrose in his thirties. She had died of tuberculosis in 1907, leaving the baby to be raised by her eldest daughter and younger sister. “Sails” was devoted to them all and wrote frequently to his daughters, but he preferred to stay afloat.

The girls concurred. A studio portrait from 1920 shows a handsome family, happy and relaxed around a proud father. But the girls were resilient and resourceful as well as beautiful; sea voyages were long and mails irregular, and for eight months after their mother’s death they’d forged her signature on their father’s allotment note, to keep receiving Henry’s pay and keep the family together. They also embroidered the truth a little locally, making out that he was a ship’s master rather than a sailmaker, and had run away to sea rather than follow in the footsteps of his stuffy town clerk father and grandfather.

In a letter written the year after his wife died, Henry describes being swept overboard in oilskins and seaboots that March during seven weeks of fearful bad weather south of Cape Horn and only narrowly escaping with his life by hanging onto the line he’d been repairing. “All I thought of when in the sea, ‘my bairns are Motherless now they are to be Fatherless’ – but God has had more for me to do, and saved me from a watery grave for a time.”

Ditton had endured “gale after gale, and the wind like to blow the old ship to pieces,” he wrote to his daughters. “I was in the sea a good while before anyone knew I was overboard, so when they did come to pull me up, I could not hold on so away I went again, I was so numbed with the icy seawater … The skipper says he never pulled so hard in his life as he did getting me on board.” The mountainous seas had also smashed the chart and wheel houses and carried away two of the lifeboats, he said.

Ditton – steel full-rigged ship built in 1891, sailed from Hamburg to Santa Rosalia, on the Pacific coast side of Mexico, in 180 days in 1907

It is an account that seems to offer little reassurance for 18-year-old Nell left caring for her three-year-old brother, but when Henry briefly attempted life ashore, his youngest daughter, Jean, later looked back on it as the worst two years of her life. The girls were used to doing things their own way, and Henry hated living on dry land. So back to sea he went. And at sea he remained.

He and Monkbarns were off Chile when the first world war began far away in Europe, and for five years they were kept busy carrying nitrates for explosives, and flour for troops – dodging enemy raiders and submarines and hunger and mutiny described elsewhere. In 1919, Monkbarns finally struggled home manned largely by apprentices. The old master and the young mate, my grandfather, quit. The “Old Man” – as masters are always called – retired to Australia, and Bert Sivell abandoned sail for oil tankers.

“Sails” hung on, and continued hanging on – patching and mending – as the ship and new young crew spent the next two years trying to beat steamers to peace-time cargoes. When Monkbarns was towed to Belgium in 1921 to be laid up alongside some of the world’s other surplus antiquated tonnage, “Sails” signed on as cook and bottlewasher. The master and mate were obliged to be aboard, but “Sails” was there, the master’s son wrote, “because he had no wish to be anywhere else”.

As the three tugs pushed and pulled them across the Channel in thick fog that September, Henry, leaning on the ship’s rail, puffing on his short black pipe as was his habit, will have passed the remains of HMS Vindictive still visible off the mole at Zeebrugge, and the deserted tangles of barbed wire in the sand dunes along the coast. Inland lay a lunar landscape of dead tree stumps, shell holes and trenches.

Monkbarns came to rest in Bruges, seven miles from the sea, beside a row of concrete U-boat pens in an outer dock a mile’s walk and a tram ride from the great medieval cathedral and picturesque canals. Beside and behind her were three other laid-up ships, including Laeisz’s Perim and H. Hackfeld, confiscated from the Germans by the Allies as war reparations to the Italians. The ink was barely dry on the treaty of Versailles, ending the first world war, and around them Belgium was a wasteland.

Pretty Bruges itself, however, had survived the war largely unscathed as an enemy-occupied marine base, where German frontline troops came for brief R&R from the mud and blood of Ypres and Passchendaele, billeted on local families or in schools and churches. Officers of the Kaiser’s army came from miles around asking to see the town’s collection of Flemish Primitive paintings. The main damage was “friendly fire” from Allied attacks, parried by the new German Flugabwehrkanonen (Flak).

By Christmas 1921, there were lights and decorations, bright shops spilling light and warmth onto the cobbles, and fantastic chocolate confectionary too amazing to eat, according to Captain William Davies’ son, Ifor, who had arrived for the school holidays in the station cabbie’s horse-drawn landau. His mother and younger brother were already living aboard.

Ifor remembered fondly the warm welcome the Welsh family received from their “well-fed” Flemish butcher and his wife and daughter in the Grand’rue and the genteel patissier where they bought their bread, cakes and groceries. Mijnheer Lobrecht produced cigars for Captain Davies and thick slabs of chocolate for the children, while Monsieur Fasnacht – “a tall slender gracious old man with a sparse imperial beard and gold-rimmed spectacles” – conjured up steaming cups of hot chocolate.

At the moorings, too, a small convivial international community had formed, with lots of visiting. Captains Graziano, da Costa and Mazzoni poured mysterious drinks in tiny glasses and their wives introduced the family from Nefyn to ravioli. Communication was fractured, but no one minded.

During the summer, Sails could watch from the rail as the children played football on the concrete floor of the old German barracks, or rowed on the canal. Sometimes they took a trip on one of the barges plying the waterway to the sea, or helped local farmers picking fruit – returning with bags of fresh produce. In winter the dock froze, and they played on the ice around the ships until Mrs Davies called them in to eat. If the weather was bad, they hung around the warm galley, watching the old Scot prepare their meals, or huddled in the sail locker to watch him pushing the big needle to and fro through the mountains of canvas with his leather sail-maker’s palm.

Laid-up or not, the work of mending the standing rigging and patching and “roping” the sails – sewing on hemp bolt-rope edges for strength and identification – continued.

Arbroath on the east coast of Scotland, immortalised by Sir Walter Scott in The Antiquary as “Fairport” (Private postcard)

Monkbarns spent 16 months in Belgium but Henry was only lured ashore once, on Christmas Eve, and then only came out of courtesey to Mrs Davies because, as her son put it, “he was a gentleman”. Mostly he kept himself to himself, refusing invitations to join the family in the saloon and settling instead in the warmth by the galley stove with his pipe. He was a keen reader with a rich booming voice, and loved to recite to himself for hours on end. He knew by heart enormous stretches of narrative poems like Marmion and The Lady of the Lake (“Where shall he find, in foreign land, so lone a lake, so sweet a strand…”)

“Most of the time, we respected his privacy,” Ifor recalled. “But once in a while Dick [the mate] would tempt us after supper to leave the saloon and tiptoe towards the galley so that we could hear Sails. If we knocked at the door he would courteously invite us in, tell us to make ourselves at home, and then, without a trace of self-consciousness or condescension, continue where he had left off.”

To Henry, the works of Sir Walter Scott were not merely pleasant recreation but also a link with home. Monkbarns is the main character in Scott’s third Waverley novel, The Antiquary; a well-to-do collector living in an ancient house Scott based on Hospitalfield, Arbroath, the leprosy hospice founded in the 13th century by the monks of Arbroath abbey. Scott had stayed there as a guest. When Sails signed on with Monkbarns he gave his address as 24 Allan Street, Arbroath.

The ship Monkbarns was one of three commissioned for a prominent local canvas manufacturer. He named them Monkbarns, Fairport (as Scott called Arbroath in the novel) and Musselcrag – the abbey’s old fishing village, Auchmithie.

Steam-powered shipping was already cutting the demand for sailcloth by 1895, when Monkbarns was launched, but there was still a living to be made in sail, where the wind was free and labour cheap, and Arbroath was a mass of saw-tooth factory roofs and chimneys to prove it.

Charles Webster Corsar could have invested in steamers to bring in the Russian flax his factories needed, but the last surviving son of the weaver with the vision to buy James Watt’s engine chose instead to build sailing ships, and with a wry flourish he named them after a historical romance.

Newspaper cutting from 1925 with Monkbarns ‘old-timers’ Sails Robertson and the ship’s cook, Josiah Arthur

A newspaper cutting from 1925 again shows Henry Robertson sitting on Monkbarns’ deck surrounded by canvas, now with the ship’s black cook, Josiah Arthur, posed beside him. The journalist describes them as “the knight of the needle and the cracker-hash king … survivors of types the world will soon know only in history”. There was hardly a square foot of Monkbarns’ canvas that had missed Henry’s palm and needles in 14 years, he wrote, and Arthur claimed to have cooked more cracker-hash, dandy-funk, and lob-scouse than any ship’s cook left in active service.

‘“No steam-boats for me, massa,” said Josh of Jamaicy,’ runs the toe-curling prose. ‘“I’ve always been used to serving out lime-juice and trimming salt-junk, and at my time ob life, massa, I don’t feel like turning on ham and eggs and peaches and cream for steam-boat sailors.”’

The crew list for that voyage reveals Josiah was in fact from from Barbados not “Jamaicy”, and that Henry had sheared ten years off his age. He still looked good. He could get away with 60.

Four years later, however, the old Scot was dead. Captain Davies, too, was dead, probably of stomach cancer. He fell ill on what was to be Monkbarns’ final rounding of the Horn and was buried in Rio. Monkbarns herself had limped back to the UK only to be sold for a coal hulk. The boy with the camera failed his sight test and never sailed again.

Monkbarns sailmaker Henry Robertson and his leather sailmaker’s “palm”, in the Signal Tower Museum, Arbroath

After a lifetime at sea, Henry Robertson finally went home to his children and grandchildren, and he lies buried with his Kate in Sleepyhillock cemetery, Montrose.

His sailmaker’s palm, a last tangible link with the ship, sits on a glass shelf in the Signal Tower museum in Arbroath – beside one last view of Henry surrounded by billows of canvas, stitching in eternal sunshine aboard Monkbarns.

*J Ifor Davies, Growing Up Among Sailors, 1983

Written by Jay Sivell

July 29, 2018 at 12:15 pm

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Other stories, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship mutiny, Seafarers' wives, Uncategorized, WWI

Tagged with Arbroath, Bruges, Corsars, Ditton, handelsmarine, Henry Robertson, Hospitalfield House, John Stewart & Co, Josiah Arthur, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, marina mercante, marine marchande, merchant navy, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailmaker, sailmaker's palm, Sailors wives, Signal Tower museum, Sir Walter Scott, square rigger, Tall ships, The Antiquary, U-boat pens Bruges, war at sea, windjammer

Lost at Sea – 81. Monkbarns, lingering traces

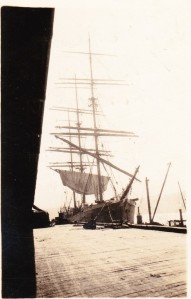

Monkbarns – and Corsar’s little white flying horse – “taken from the bowsprit end, plunging her nose in a foaming billow,” as the Sydney Morning Post correspondent put it. Photo E. Bainbridge estate

A colour piece in an Australian newspaper reflects the end of days for sailing ships like Monkbarns. While the writer “Sierra” was sauntering among the old-town dockside pawnbrokers and marine artists’ shops in Sydney as the Twenties roared around them, Monkbarns was being towed to Corcubion with her final cargo – to serve out her twilight in northern Spain as a coaling hulk for Norwegian whalers. Astonishingly, she remained afloat until the late 1960s.

“…Here are ship-chandlers, seamen’s fitters, sail makers, fried fish shops, and Chinese laundries, pawnbrokers’ and curio shops packed with treasures from foreign lands, and nautical instrument makers … A peep at the curio shops sends the mind foaming in strange places. Chinese gods and ivory pagodas, chopsticks, Polynesian canoes, Burmese tatooing instruments, sea shells from every strand, guanaco skins from Patagonia, Esquimaux fish hooks and Zulu knobkerrles guide the roving fancy through mysterious lands.

Pawnbrokers’ windows bear witness to the pride once taken by seafarers in the art of sailoring. Stowed away here are the relics of a vanished race; their prized marlin spikes, their fids, prickers, sewing palms, and their Green River knives. Here, too, are their concertinas, sou’westers, badge caps; oilskins that seem to have caught and held a watery gleam of Cape Horn sunshine; a pair of evil-looking knuckle dusters, perhaps the last marketable possession of some stranded bucko mate; a rust-bitten cutlass, and ancient sea boots with desiccated dubbin still adhering in the cracks, reminiscent of the days when sailors really paddled about in salt water.

But the most fascinating shop of all is that of the marine artist. Tea clippers, wool ships, brigs and schooners, under flying kites or stripped for storms, are depicted cleaving the seven seas. Some, framed in miniature ships’ wheels and lifebuoys, are seen bounding along under the bluest of skies, their gaudy colours streaming from peak and masthead in greeting to distant promontories.

All the old-timers are here. The Great Britain in her glory of full canvas, and, in her decrepitude, a hulk at Falkland Island; the Cutty Sark running before a rousing gale; green Thermopylae racing up Channel under a cloud of stunsails; the stately Macquarie placidly gliding over smooth water; and the Loch Katrine, dismasted in a hurricane, her mainmast gone by the board, and her fore topmast diving into a turbulent sea.

schooner deckloaded to the shearpoles waddles behind a squat tug; the barque Vincennes Iies wrecked on Manly Beach; and a superb clipper rounds to and drops anchor, her sails thrashing in the wind so naturally that the thunder of her canvas seems to reach the ear.

But it is only the rumbling of a six-horse lorry passing along this enchanting street.”

Written by Jay Sivell

July 16, 2018 at 5:20 pm

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Historical postcards, Other stories, Uncategorized

Tagged with Bert Sivell, Circular Quay, Cutty Sark, handelsmarine, Illawarra, John Stewart & Co, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, Loch Katrine, Macquarie, marina mercante, marine marchande, merchant navy, Monkbarns, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, square rigger, SS Great Britain, Sydney. NSW, Tall ships, Thermopylae, Vincennes, windjammer

A sailor’s life – 80. Worse things happen at sea: the steward’s story

Monkbarns unloading nitrates in Walsh Bay No 10 Sydney, May 1925 (Copyright estate of Eugene Bainbridge)

David Morris called himself a journalist, a writer. He’d been on the lookout for a job on a square rigger for months before he heard of Monkbarns in Sydney in June 1925. He wanted “atmosphere” for some historical sea stories he was preparing to publish, he told the Newcastle Sun as the ship loaded Australian coal for South America. He wanted thrills, he wanted to “see the Pacific at its worst”.

Around him on deck, eyes slid away. “Some of the crew, with that superstition born in seamen, are inclined to regard him us a hoodoo,” the reporter noted.

Three weeks earlier Morris had shot across to Walsh Bay, Sydney, where the ship was discharging nitrate, and buttonholed the mate, offering himself in any capacity at a nominal wage. The mate had said “Nothing doing”, but as he trudged off down the gangway, they’d had a rethink. If he really wanted the experience, said the master, he could come along as a general helper at £2 a month (about £1,000 per annum today.)

Was it a cheap shot they’d expected him to refuse? Morris called himself the Captain’s steward, though he appears on the crew list as Cabin Boy, but pay for a seaman was £10 a month, not £2. Then again, as steward or “boy” he didn’t have to go aloft in all weathers or stand his trick at the wheel. He was a housekeeper, minding stores and dispensing first aid.

“Yesterday Morris was caught sewing his shirt, with stitches that would disgust a housewife, on the steps leading to the poop deck. He is a well-built man of 25, but he looks more like 30. The small moustache on his upper lip, and the tan shoes and the tweed suit already soiled by work in the galley, looked strangely out of place there,” said page 6 of the Newcastle Sun.

Movie poster for The Ship from Shanghai released in 1930 (http://adventures-of-the-blackgang.tumblr.com/

London-born Morris had visited most ports in the world as a passenger, and had slept in some of Australia’s best hotels and its least inviting parks in his quest for “atmosphere”, readers learned. He had been inspired to join Monkbarns by the runaway success of a sea thriller published the previous year by another young Australian journalist, Dale Collins. Ordeal is based on a round-the-world trip Collins made aboard the motor yacht Speejacks as historian to the US cement magnate Albert Younglove Gowen, who happened to be on his (second) honeymoon. The novel – about seamen turning on their idle rich passengers – was filmed in 1930 as The Ship from Shanghai, with Louis Wolheim as the ship’s crazed steward who holds them all hostage.

Morris was quite frank about what he was up to; there were men on Monkbarns who had had remarkable experiences, he told the newspaper, and he wanted to “chase up” some of those real-life stories. But he seems to have fallen short on listening. This may have been a world of horny-handed hard cases risking life and limb in all weathers aloft, but they still wouldn’t set sail on a Friday, or whistle for fear of challenging the wind, or even say “pig” out loud.

Of the 28 men and boys who had left Liverpool in March 1923, one was dead – a 19-year-old apprentice lost lashing down an escaping sail during a hurricane – two had been left behind in hospital injured, and two more would die before they dropped anchor back in the Thames in 1926.

Monkbarns 1923 securing lifeboats under heavy seas off the cape (probably photographed by 3rd mate Malcolm Bruce Glasier)

By June 1925, only the captain, the mate, “Sails”, a couple of ABs and the older apprentices remained of the original company. It was they who had faced down disaster on the passage out, when a hurricane south-west of Good Hope knocked them so badly that the cargo shifted. With the lee side of the ship 12ft under and green seas raking the deck, it was they who had risked their lives deep in the hold, shovelling rock salt uphill for three days to try to right her. Young Cyril Sebun was lost off the upper topgallant yardarm while they laboured. But nothing could have been done to save him. The boats were all smashed.

Eventually, they put into Cape Town in distress – a first for Captain William Davies. “During my forty years of service in sailing ships I have never had an experience that can in any way compare with this recent one, and to be quite frank, I should not like to pass through a similar ordeal again.”

On arrival in Australia, three seamen deserted – abandoning their pay – and Morris’s predecessor killed himself with an overdose of chloroform. He had been drinking heavily, the inquest noted. He was buried in Stockton NSW, where some of his former shipmates from the SS Argyllshire called the following spring. They sang Welsh hymns at his grave, and laid artificial flowers. They knew.

So, it was not surprising that Morris’ taste for ill winds made his shipmates uncomfortable and by the time Monkbarns had been at sea for two months, things had turned nasty.

Three entries from the diary kept by one of the apprentices, Eugene Bainbridge, offer a snapshot: 23.8.25. Sunday. Played Bridge all day and was 600 up to finish. It has been quite parky lately and it was anything but warm at the wheel from 12-2 tonight. Course ENE, on starboard tack. Shaved David Morris’s beard in half deck after putting him forcibly on the floor. He seemed a bit peevish and didn’t play ‘Vingt et un’ very well afterwards. The job we made of his beard wasn’t very good.

24.8.25. Monday. Clear, calm, sunny, fresh. Doing about 2-3 knots. Course ENE. ‘Maurice’ came in for about two minutes tonight. He seemed to know that there was something in the air and beat it.

The Pelican Society photographed by Eugene Bainbridge – Newcastle-Callao 1925 (Copyright estate of Eugene Bainbridge)

25.8.25. Tuesday. A night of revelry of a peculiar sort. The subject was ‘Maurice Moscovich’. Notices were posted on the half deck doors inviting you to a singsong to be held in the fo’c’sle at 6.30pm. The Mate was particularly asked to refrain from blowing 2 whistles and when told why, was quite sympathetic. At 6.30 sharp, we met and the subject [Morris] had wandered into the gay party.

It was a bluff. He was to be seized in the middle of its proceedings and tried by the chief Pelican and his confederates. All passed off as planned and the victim was found guilty of not supplying the fo’c’sle with molasses and duly sentenced to have his port beard and starboard ‘tache shaved off. Cold water was used to emphasise the gravity of the act, and Bill Hughes, the Court Hairdresser, operated.

But worse was to come, because Morris evidently put up resistance to the assault, verbally if not physically. Bainbridge, a 21-year-old ex-boarding school boy from Maida Vale, London, records that the victim was deemed to have been “unduly insolent” to his tormentors – and a vote for death by dropping over the after part of the poop was passed.

Maurice Moscovitch as Shylock at the Royal Court, London, 1919 (From: http://exhibitions.europeana.eu/exhibits/show/yiddish-theatre-es/jml-las-obras/item/130)

It is possible that there was more than a little anti-Semitism in this “hazing” as Maurice Moscovitch was a well known Russian Jewish stage actor that summer wowing Australian audiences with his Merchant of Venice and Morris’s middle name was inscribed on the crew list as Isidor. Bainbridge had been to see Moscovitch at the Criterion theatre while Monkbarns was in Sydney.

More worrying still, the punishment meted out – for poor stewardship of the few treats that made the ship’s diet of salt meat and pulses bearable – apparently had the backing of the Master and the Mate. Bainbridge writes: We next trussed him up in a sack etc and took him aft for the mate’s inspection.

The procession marched solemnly back singing ‘For it’s a Lie’. Prisoner was next trussed up again (more securely) and taken forth to his execution. Maurice was marched up on to the fo’c’sle head and lowered away over the break. The wash tub was underneath and someone was making a noise like water. The stunt worked so far and when about a foot off the deck, the word was given and Maurice was dropped!!! He arrived in a heap at the side of the ‘donkey’ [steam winch] amid cheers and benedictions from the High Priest.

Had Morris believed his hostile playmates were actually dropping him gagged and bound into the Pacific? It seems more than possible, but he showed his mettle by joining them in the fo’c’sle, where proceedings continued as a “sing song”, and reciting a chunk of Kipling for the company. Whereupon everyone joined in a hearty chorus of “For he’s a jolly good fellow” and peace descended. Bainbridge wrote: The Old Man and Mate were both observed to be enjoying it uncommonly.

Many years later, “Bill the Court Hairdresser” – by then Captain William Hughes, sir – remembered David Morriss [sic] and his quest for atmosphere. “He got it all right, and I’m sure that what he went through before reaching London would fill two or three books,” he told AG Course, chronicling the history of the John Stewart ships for his book The Wheel’s Kick and The Wind’s Song.

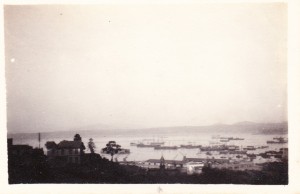

View of Valparaiso harbour with Monkbarns marked by apprentice Eugene Bainbridge with an arrow at the bottom (copyright estate of Eugene Bainbridge)

Two months later, just outside Valparaiso, he was still annoying the apprentices (Dave joins us, and we are bored to a standstill with his platitudes!) but he’d graduated from ‘Maurice’ to Dave. And in port, Dave showed a pleasing openhandedness with the ship’s stores as the apprentices rowed around visiting and being visited by boys from neighbouring ships. (Dave got us some stores and there was plenty of scoff. He unfortunately spoilt this good turn by telling some of his tall yarns.)

However, as soon they put out to sea again and rationing restarted, the moans resume. 9.3.26. Dave wants to substitute sugar for molasses instead of substituting jam. This is not a fair exchange as sugar doesn’t go well with bread and butter! 5.5.26. Dave has been making mistakes with the weighing out of the butter and the tins containing so painfully small a quantity we complained and found we were getting less than our whack!

Happily, nine months after Morris’s sentencing by the Pelican Club, the horseplay had become rather more inclusive, if no less rough. By then, Captain William Davies was dead in Rio de Janeiro, the Mate was the new Old Man and the ceremony as Monkbarns passed Lat 0° 00’ 00” was a more or less welcome letting off steam after a very trying few months fighting their way round the Horn with the dying man refusing to put into port.

Young Bainbridge had a ringside seat. 9.5.26. Sunday. Crossed the Line last night. We all ‘felt the bump and noticed that the ship was going faster downhill!!’ At 1.30, I was let into the secret by Bill that we ‘offenders’ had to ‘go through it’. The Old Man had made some pills of ginger, glycerine and several other ingredients and covered them with sugar (of which there is a very large quantity aboard from Rio.) Jim had made some very ‘choice’ mixture of tar, tallow, soap, Melado (molasses) and red lead.

Monkbarns, Neptune’s court May 1926 – crossing the Line. Neptune and wife right, Dave Morris and Eugene Bainbridge among the tarred six on the left (copyright estate of Eugene Bainbridge)

In time honoured tradition, Neptune appeared over the side clad in oakum and bearing a huge trident made from the mast of the for’rard boat, accompanied by his Wife, his Barber, his Parson – in a lead foil cassock and paper collar – and his Doctor carrying the bag of pills. They set up court on the main hatch.

Bainbridge and Morris were among six “first trippers” the god of the sea wanted to inspect for fitness.

I was first blindfolded and then marched to the main hatch, falling over several ‘lines’ drawn across the deck. We had made the washhouse door fast and they had to break the handle off to get in. I was first asked by Neptune why I had done this and if I had crossed the Line before and why I hadn’t been ‘put through it’!

I then kissed his wife’s foot, which was covered with tar and was then shaved using the mixture, getting plenty of it in the mouth. I received the pills and spat them out. At a second shot, I managed to conceal one behind my tongue but before I could remove it my mouth was sore! I finished up being tipped backwards into a tub of water and then liberated. After I had seen two or three others done I went onto the boom and caught a 24lb bonito, which we had for tea. The proceedings broke up with all hands ‘splicing the main brace’.

They were back in the northern hemisphere after three years away, and “home” suddenly seemed closer. But Monkbarns’ adventures were not over. Progress was slow. Supplies ran out. By 450 miles off the Lizard they were down to rice and ersatz bread, but once into the shipping lanes an obliging German steamer provided relief.

They brought the boat alongside and the provisions pulled aboard: three sides of bacon, two hams, two cases of spuds, three sacks of flour and about 16 tins of Argentine boiled beef (we had some for tea and it was excellent), a certain amount of margarine and butter for the cabin, also lard and Dutch evaporated milk. Then the Cook gave us curry and rice for breakfast!!!!!!!! It was nearly the last of him.

But two weeks later they were still 12 miles off Portland Bill, and “reduced to rice, tea and a little jam and bread”, according to another unpublished diary of that voyage, by able seaman Dudley Turner. “Not had a smoke for weeks, which makes matters a lot worse.” And the Old Man was refusing to flag down any more ships.

When they picked up the pilot off Dungeness and it was discovered he handed out cigarettes for good steering – the first tobacco seen aboard for weeks – there was a rush to relieve the wheel frequently. “Never had such good steering been seen before by the old ship,” wrote Course. But they were so undernourished that the tug crew had to help them haul the hawser aboard.

At 6pm on 10 July 1926, Monkbarns dropped anchor off Tilbury. The pilot presented them with a sack of potatoes and Bainbridge records a “memorable feed of sausages and boiled spuds!!! Never was a meal so appreciated”.

The following day they were towed up to Charlton Buoys, a vessel from a bygone age gathering crowds on the banks, and there the crew were paid off.

And there the story ends. Monkbarns was sold “foreign”, and towed to Corcubion in northern Spain to end her days as a coal hulk. Eugene Bainbridge abandoned the apprenticeship for which his father had shelled out £42 and never went to sea again. What became of David Morris I cannot tell. Bill Hughes thought he’d gone in to radio in Melbourne. If he ever wrote up his historical sea stories, neither AG Course nor I could find a trace.

Bizarrely, the real thrill-seeker aboard Monkbarns that trip turned out to be the youngest apprentice, 17-year-old Len Marsland of Brisbane. After rounding the Horn in sail, in 1929 he pops up as a member of Sir Douglas Mawson’s Australian Antarctic expedition. He worked as a prison guard in Canada, chased the explorer Sir Hubert Wilkins across the Atlantic in an attempt to sign up for his submarine expedition under the polar ice, reappeared in Reykjavik, erecting a signal station, and then back at sea as an officer on an icebound freighter in the Baltic and facing down machineguns in a Russian Black Sea port. Tragically, Marsland’s adventurous career was short. While working as a stuntman for Sir Alan Cobham’s famous flying circus in 1935 his parachute failed to open. He fell 1,000 feet and died in Esher, Surrey, aged just 27.

Previously: A doctor aboard 1913

Written by Jay Sivell

May 29, 2016 at 12:39 pm

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Other stories, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, Uncategorized

Tagged with AG Course, apprentice, cabin boy, Captain Bill Hughes, Captain William Davies, Cyril Sebun, Dale Collins, David Isidor Morris, discipline and desertions, Eugene Bainbridge, first tripper, Frederick Leonard Marsland, handelsmarine, John Roberts, John Stewart & Co, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, marina mercante, marine marchande, Maurice Moscovitch, merchant navy, Newcastle NSW, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, seamen's pay & conditions, ship's steward, square rigger, SS Argyllshire, Tall ships, The Ship from Shanghai, Valparaiso, Walsh Bay Sydney, windjammer

A Sailor’s Life – 79. Doctor aboard (1913)

Tramping round the capstan, Monkbarns, by apprentice Eugene Bainbridge, 1924-26 (copyright: Estate of Eugene Bainbridge)

Much of what we know about the dying days of sail was recorded after the First World War, when most of Britain’s last old sailers had been sunk or ‘sold foreign‘.

Eric Newby’s The Last Grain Race and Elis Karlsson’s excellent Pully-haul were published as late as the 1950s and ‘60s, both about what were by then Finnish-owned vessels – the Moshulu, now a restaurant (!) in Philadelphia, and the Herzogin Cecilie, a wreck off Salcombe, Devon.

But in the summer of 1913, when the Liverpool-registered square rigger Monkbarns arrived off Australia from South America with a state-of-the-art Cinematograph movie camera provided by the Kineto film company of Wardour Street, London, “Everything that could be filmed about life aboard had been filmed,” the resident amateur cameraman noted.

Dr Dudley Stone was a keen yachtsman and junior doctor at St Bart’s hospital London who had joined Monkbarns in Gravesend that February determined to chronicle what was even then obviously the end of an era, from “swinging the ship” for correcting the compass before they sailed to the shanties round the capstan as they weighed anchor. His commission was to “obtain pictures of the ocean in its angry moods”. It was Kineto’s second attempt, after the chap it sent out the previous year had found himself vilely incapacitated by seasickness.

Over the months that followed, as Monkbarns crossed the Atlantic to Buenos Aires with a cargo of cement and then headed back eastwards in ballast round the Cape of Good Hope to Sydney, he shot 9,000 feet of film: of the men hauling and chipping, of the view from the yards, of big seas and the master in his oilskins. He developed it in his cabin and dried it all in strips festooned around a lazarette under the fo’c’sle head.

“I have cinematographed with no gloves and with oilskins and top boots on from aloft from almost everywhere.” Dating and developing it all had taken up to five hours a day, he wrote from Newcastle NSW.

Sadly, this nearly two miles of film seems to have disappeared. It is mentioned in the Australian newspapers of the time and was picked up years later by Captain “Algie” Course during the fireside yarns with fellow Cape Horners that formed the basis of his account of Monkbarns in The Wheel’s Kick and The Wind’s Song, but of the actual film there is no trace, not in the National Maritime Museum collection, nor the British Film Institute, nor the Australian Maritime Museum in Sydney. Shot from a heaving deck over 100 years ago, washed in saltwater, dried in a dusty locker and exposed to sulphur fumes when the ship was fumigated in Newcastle, it is unlikely any of it has survived.

Dr Stone’s unfinished diary, however, did survive – in the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich – and even without moving images it provides a rare glimpse of working life aboard one of the last British full-rigged ships a full 16 years before Alan Villiers and his ill-fated colleague Ronald Walker immortalised Grace Harwar, the last full rigger in the Australian trade.

Stone and his friend and patient, the Honourable John Gilbert Eveleigh-de Moleyns, aged 34, fifth son of the 4th Baron Ventry, were an odd couple aboard a working ship; de M’s condition is not identified but he lay down every afternoon, and usually played Euchre with the Mate for matches in the evenings or made quoits, which he played on deck when the weather permitted. Meanwhile, Stone was out along the yards or down the holds in all weathers with his Cinematograph, filming, or learning to take a noon sight and wrestling with calculations of the ship’s position and progress.

Neither did any actual work aboard, apart from “tailing on” occasionally.

But they roamed at will armed with a Videx Reflex and a Brownie, and Stone’s eye was keen. He noted the pilfering of stores by the ever-hungry apprentices, rough justice for a suspected thief who was given a hiding by his shipmates and booted ashore in Buenos Aires, and the stowaway “discovered” drinking tea in the fo’c’sle after they sailed. The Mate hadn’t known he was aboard, but the master did. Desertions had left him shorthanded. Two “stowaways” appeared after the ship had sailed, and both were entered on the articles at £1 per month.

Patrick Haggerty was an Irishman from Queenstown, Cork, red haired, blue eyed and popular. A fine shantyman, said Stone. He claimed to be off an Italian barque that had gone ashore near Buenos Aires and had only the dungarees, socks, cap and shoes he stood up in. After he was found half frozen at the wheel one night, the ship had a whip-round for him: the Mate gave him a shirt and an old oilskin, de M donated pants and socks, Stone rooted out an ancient spare jersey.

Stone’s surviving diary begins as they leave Buenos Aires.

A doctor was a familiar sight on passenger steamers, schmoozing the saloon crowd and keeping at bay any unpleasantness from steerage. Naval vessels too usually had a surgeon, to patch up battle injuries. But merchant ships knocking about the world with cargoes of nitrate or guano rarely enjoyed the luxury of trained medical assistance.

In the days of sail, physicking the crew was the responsibility of the “Old Man”, supported by a dog-eared copy of the Ship Captain’s Medical Guide and a case of pre-mixed bottles and papers labelled Solution No. 5 and Powder No. 3. Far from land, way off the steamer tracks and with no wireless to call for help or seek advice, the master had to rely on common sense and caution. Any ailment that didn’t involve actual blood loss was potentially malingering, and logs show intervention was rarely rushed. It is hardly surprising then that the presence of a bona fide doctor aboard Monkbarns was greeted with enthusiasm by her crew.

They set off from BA with all seven apprentices and three of the fo’c’sle down with diarrhoea, due to “the change of water”, the master diagnosed, and throughout what was to prove a very rough passage Dr Stone was kept busy.

Within a week storms were raking the ship. It was hard to sleep, wrote Stone. The main royal broke loose and tore both sheets out. The foresail ripped the starboard reefing jackstay clean off the yard, and the fore topmast staysail chafed most of the way through its bolt rope. In the store room all the pickles and a case of kerosene were lost. The following morning Stone watched the steward and two of the apprentices leaping about among the stores trying to catch tumbling tins. “Some had burst (I only hope they are the ‘blown’ ones I saw and that we will be saved from Ptomaine poisoning)”.

The fore hold was a jumble. There was rope everywhere, hanging over the edge of the ‘tween decks and tumbled below. The ship had acquired a list to starboard, and was rolling badly. The skipper had told him the squalls had been hurricane force 11 to 12, and that they might not have survived the night if the ship had been loaded. The boys’ half-deck had flooded.

Stone, who did not have to get up in the night to clamber aloft replacing blown-out sails, or sleep on a wet bunk in wet clothes, was amused to note that all the master’s drawers had shot out and his rug had spontaneously rolled itself up, but he was less pleased that the loss of the oil meant lights out at 9pm. There were only four candles aboard (his and de M.’s) and the ship was “badly found for matches”.

As paying passengers Stone and de M. occupied separate cabins in the saloon aft, with a porthole and two bunks each for all their gear. This left Leslie Beaver, the out-of-time apprentice acting 3rd mate, relegated to the lower bunk in the 2nd mate’s cabin.

“The Mate’s and 2nd mate’s cabins were like store rooms for nick-nacks and old rubbish. Their doors being opposite each other the contents of both cabins were well mixed. I just missed being hit by a camp stool paying a flying visit from 1st to 2nd’s quarters. Beaver had the much used water in their basin, the contents of a water jug and a tin of Swizo milk spilt into his bunk. He borrowed rug etc from de M. for night ”

More seriously, one of the ABs was injured. “Whole gale, hurricane squalls. Tremendous big NW Sea,” recorded the mate. “W Chapman knocked down and hurt.”

On June 7, Stone saw six “patients”, including Chapman, whose leg was skinned from knee to ankle. My own grandfather, then an apprentice of 18, sidled into the narrative with a tap at the doctor’s cabin door that evening. Stone noted an inflamed ligament, painful to the touch and prescribed iodine.

Captain James Donaldson was not pleased, though whether it was the molly-coddling or the lèse majesté is unclear. On June 11, Stone noted: “9.30 Went the rounds of the fo’c’sle at skipper’s invitation – a gentle hint that he does not like my going there on my own.”

Chapman’s raw leg was much better, a swollen knee was down and young Sivell was back at work again, against medical advice – (fed up with doing nothing, noted Stone.) Meanwhile, there was a strained shoulder to inspect (“nil to be seen. I’m safe…”), and the 3rd Mate had been shot into the scuppers on his stomach during a particularly heavy roll, resulting in appalling bruises but fortunately no internal injuries.

And still the glass continued to fall, down to 28.58. The fore lower topsail carried away.

At 3.30am, on a page labelled Hurricane, Stone recorded: “Broached to on port tack – my top row of bookshelf showered its contents on my head and then continued across cabin. Got up and collected them. 4 Very heavy squall carried away fore topmast staysails and new No 1 canvas sail. 7 de M came over to me and I produced LGCL book on meteorology and we tried to make out what position we were in with not much success. 7.30 Hot coffee went the rounds. 8 Broached to on port – more things going to leeward – thank goodness the ballast remains a fixture. This is as heavy a blow as any of ship’s officers have been in. I certainly cannot imagine more wind or a bigger sea. I heard that at 3.30am the 2nd mate and a hand went aloft to see to upper fore topsail and that on coming down he stepped into lee scuppers, which were full up with water. He is a short fellow and was up to his neck. That I think gives me some idea of the sea shipped on broaching to, and we in ballast.”

The Old Man – who was 64 and had been up all night – was laid up with cramp in the chart house, and the foremast staysail was a rag.

The hurricane squalls and strong gales continued for three weeks, almost without let up. Stone and de M. would tell the newspaper reporters waiting in Newcastle that they were both “ardent lovers of the sea” but neither of them ever wished to undergo such an experience again.

Monkbarns was one of five sailing vessels that arrived at Newcastle on the weekend of 5th July 1913, including the full-rigged Ben Lee, which had sailed from Buenos Aires two weeks before her. All had suffered. Ben Lee’s lower topsail had carried away and the foresail was blown to pieces. Kilmallie, from Santos, lost a lifeboat and her ballast shifted. The barque Lysglimt, from Natal, was knocked onto her beam ends when her ballast shifted, and the crew spent three death-defying days in the hold trying to right her, the Sydney Morning Herald reported.

Despite or possibly thanks to the hurricane, Monkbarns had made the passage in 52 days, to Ben Lee’s 67. Our man on the docks reported that two of Monkbarns’ crew had been injured and had been “attended by Dr M Stone, a passenger”.

Up in Newcastle, (where they went because there was smallpox in Sydney and the city was about to be quarantined), the Newcastle Morning Herald & Miners’ Advocate produced a much juicier report, headlined “An interesting visitor”.

Dr Stone, it said, had been imprisoned by Germany for spying the previous year (shades of Erskine Childers‘ The Riddle of the Sands). Dr Stone did not deny it. He had been one of a party of five well-to-do British yachtsmen – including the marine artist Gregory Robinson and the engineer William Richard Macdonald, who happened to have patented a nifty bit of submarine technology. They had attracted unwelcome attention from the German military authorities by happily photographing naval installations along the Kiel canal. It had taken them five days to talk themselves out of jail.

During the war that broke out less than a year after Monkbarns’ arrival in Newcastle, Stone would serve in the Royal Army Medical Corps. He became an eminent radiographer, with an obituary in the British Medical Journal in 1941.

The Kineto company, however, folded in 1923 and de M died in New Zealand in 1928, the year after Monkbarns was hulked off Corcubion, in northern Spain.

Stone carried on yachting all this life. Perhaps he even shot more films. But what became of his footage of working life aboard a British ship in the last days of sail remains a mystery.

*

An edited version of this article appeared first in The Cape Horner magazine, the journal of the International Association of Cape Horners. August 2015.

Photographs by Eugene Bainbridge, who was Monkbarns’ last apprentice during her final voyage, 1924-26. He joined her in Newcastle NSW, having steamed out from the UK third class aboard the P&O passenger ship Barrabool. He was then 19, the privately educated only son of a maritime insurance broker from Surrey. He had a Leica camera and for two years he kept a diary and took pictures of life aboard. Neither the diary nor the photographs were ever published and Eugene never went back to sea. These previously unseen views are made available by kind permission of his family.

Next: Worse things happen at sea

Previously – Flowers in Hong Kong, Medals in the Post iii

Read from the start:

A sailor’s life – beginning, middle and end

Written by Jay Sivell

May 8, 2016 at 2:10 pm

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Historical postcards, Isle of Wight & Sivell family, Other stories, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, Uncategorized, WWI

Tagged with apprentice, Ben Lee, Bert Sivell, Captain James Donaldson, Cinematograph, Dudley Macauley Stone, Eugene Bainbridge, handelsmarine, health at sea, injuries in sail, Isle of Wight & Sivell family, John Gilbert Eveleigh-de Moleyns, John Stewart & Co, Kilmallie, koopvaardij, last days of sail, Leslie Beaver, life at sea, Lysglimt, marina mercante, marine marchande, merchant navy, Newcastle NSW, passengers on sailing ships, seamen's pay & conditions, square rigger, storms at sea, Tall ships, unpublished footage of sea, Videx, William Chapman, windjammer

A sailor’s life – 75. Sniffing Stockholm tar

In my sailor grandfather’s footsteps I have blagged my way into an oil refinery and onto a Shell tanker, I’ve crossed the Atlantic by container freighter and dropped a wreath into the night black sea at 49° 35’N, 19° 13’W where he and his final crew were lost – I have even traced and befriended the last old man of the U-boot crew that killed him.

For nearly 20 years I have read letters and diaries, rooted through archives, pored over photographs and asked damn fool questions of elderly seafarers who have shared their yarns with gentle amusement. But I remained an armchair sailor, sitting in the warmth, reading about a life beyond my understanding.

It was on a wet day in Liverpool docks that I ran into the Stavros S Niarchos, a dinky, modern sail training brig – square rigged on two masts, a charity venture providing outdoor challenges to young people.

And also, it transpired, to the not so young. Anyone up to 80 could have a go, said a grey-haired woman on the quayside. Was I too old to climb out along the yards, I asked – to try to experience what 16-year-old Bertie Sivell had seen and felt when he first went aloft a hundred years ago? Certainly not, she said, she had.

The author – climbing past the fore t’gallant (right) to the royal beyond, where photographer is perched (see boot).

Anyone who ever read Treasure Island under the bedclothes and fell asleep dreaming of clambering among the spars of a tall ship will understand (and we who read by torchlight in the old days before duvets and Kindles know who we are). To swing up the swaying ratlines and out along the foot-ropes, and see “my” ship splice the waves 120ft below; to roll along a pitching deck, at one with the swell, dodging sheets of spray; and to lie down each night tired but buzzing and be rocked to deepest sleep?

I signed on.

Stavros is not Monkbarns. For a start she is smaller, with two masts not three and fewer yards and sails. She also has two engines, GPS, refrigeration – and heat and light and hot showers and plenty of fresh water and good food. In fact, my grandfather would scoff that my so-called experience in sail bears more resemblance to glamping than the conditions he endured when he began his career at sea as an apprentice in Monkbarns in 1911.

What a difference 100 years makes. The barrels of pork and beef gristle in brine are gone. The yawning cargo hatches and mountains of coal or guano, or slimy stone ballast, that had to be winched in or out basket by basket are gone. Nowadays safety lines snake up the ratlines and along the yards, where there was once only a boy’s own grip. The old cry of “One hand for the ship and one for yourself,” is not quite so scary when you’re wearing a stout harness and clip-on carabiners. Monkbarns suffered countless injuries, as well as losing two young lives overboard in just three years in the early 1920s – Laurence O’Keeffe off the jib-boom and apprentice Cyril Sibun in a fall from the fore upper t’gallant. They were 18 and 19.

On Stavros clean, dry pipe cots with reading lights and lockers fill the t’ween decks where Monkbarns’ apprentices would have shovelled and sweated to trim (balance) the cargo, and out along her bowsprit net “sailor strainers” prevent accidents. But working a sailing ship is still not for the faint hearted.

I have shuffled out along the yards, muscles cracking as I wrestled to haul up and lash down the heavy clew of the sail high out over the waves. I have swung one-armed under the great steel yards, groping for gaskets blowing in the wind, and tied knots one-handed up and down the jackstays.

I have tailed on and hauled “with a will” among ill-assorted strangers until my shoulders strained in their sockets and the hairy hemp lines blistered my office softy palms, and rolled into my bunk sound asleep at 8pm to rise again fully clothed at midnight, to relieve the watch on the open bridge, donning gloves, scarf and waterproofs against the cold summer night. In a week the motley novice “crew” – paying travellers of all shapes and sizes – find themselves fused into a team. A ship’s crew. (Although our professional merchant navy officers probably think fondly of the days when a sailing ship cargo lay inert in the hold for the duration and didn’t need wetnursing.)

Together we have seen sails silhouetted against the stars – more stars than most of us city dwellers ever imagined, and the milky way arching overhead from horizon to horizon. We have sailed into the sunset and watched for dawn, eyes peeled for the pin prick lights of the fishing fleet. We have learned the ropes, and the buoys and the markers.

So far I have not been out of sight of land for more than a week, much less braved day after relentless day of gale-force winds, or icebergs round the Horn, but I have felt the pitch and roll of a tall ship doing 10 knots under sail and watched the horizon tilt and tip under the solid curl of the mainsail. I know the sound of the seas crashing past the scuppers and have tasted salt in the spray.

I may be just paddling in the shallows of my sailor grandfather’s life, but I have sniffed Stockholm tar.

Suddenly, the dusty records have colour and movement. This winter I shall abandon the archives again and join the paint gang aboard Stavros in Liverpool docks, chipping and cleaning, learning “my” ship from the rivets up, and next spring with a crisp CRB certificate in my pocket I hope to sail as volunteer crew – as cook’s assistant, if that’s what the ship needs.

Somewhere, my grandfather is laughing.

Previously – Monkbarns: Britain’s last Cape Horner?

Next – The medals in the post

Read from the start:

A sailor’s life – beginning, middle and end

Written by Jay Sivell

October 14, 2014 at 9:46 am

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Modern square-riggers, Other stories, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, Uncategorized

Tagged with aloft, Bert Sivell, brig, crewing, Cyril Sibun, first tripper, handelsmarine, Isle of Wight & Sivell family, koopvaardij, last days of sail, Laurence O'Keeffe, learning the ropes, leisure sailing, life at sea, marina mercante, marine marchande, merchant navy, rigging, sail training ship, sail training vessel, square rigger, Stavros S Niarchos, Stockholm tar, t'gallants, Tall ships, Tall Ships Youth Trust, Tenacious, voiliers, windjammer, zeilschepen

A sailor’s life – 74. Monkbarns: Britain’s last Cape Horner?

She was obsolete the day she slipped into the Clyde in June 1895: a steel-hulled, full-rigged, three-masted windjammer launched into an age of engines barely two years before Rudolf Diesel changed the world of shipping forever.

The flax mill owner who had commissioned her, Charles Webster Corsar of Arbroath, named her Monkbarns after a local character from a Walter Scott novel (The Antiquary) and demanded everything of the best. The decking and rails were of teak, the accommodation for officers and crew particularly fine. “Her outfit includes all the modern appliances for the efficient working of such a vessel,” reported the Lennox Herald, the Saturday after she was floated.

As a final touch, Corsar even gave her a little white Pegasus figurehead – which would make Monkbarns and her “Flying Horse line” sisters, Fairport and Musselcrag (1896), recognisable around the world. It was not whimsy but canny branding: Corsar’s flax mills and manufactory in Arbroath supplied the sailing ship canvas sold by the family’s cadet branch, D. Corsar of Liverpool – every bolt of it stamped with their trade name, Reliance, and a little flying horse.

The Lennox Herald did not mention the figurehead, nor any further detail, merely remarking that the naming ceremony was carried out by Mrs David Corsar, Jnr, of Cairniehill, Arbroath.

The launch of Charles Corsar’s full-rigged ship Monkbarns, reported in the Lennox Herald, West Dunbartonshire, Scotland, in June 1895

In fact, the launch by Messrs Archibald McMillan & Son (Limited) merited only a single paragraph in a round-up of Dumbarton news that week, wedged between reports about two men being fined 20 shillings each for driving without lights and a rumour in the Glasgow Herald that the Union Steamship Company of New Zealand was buying five new steamers, possibly from Dennys of Dumbarton, which had “built the greater number of vessels for the line, and will probably run a good chance of getting at least some of the work”.

The reporter’s description of Monkbarns having “all modern appliances”, however, echoed down the years. Frank C. Bowen wrote in 1930 that she had “every modern labour-saving device for working the cargo and sails” (Sailing Ships of the London River), and most subsequent authors took him at his word. Yet Monkbarns’ apprentice boys might have considered the matter rather differently.

Like every other sailing ship of her age, she had neither light nor heat. The White Star liner Majestic, completed five years before Monkbarns, catered for 4,100 passengers with an à la carte restaurant and Pompeian swimming pool. But Monkbarns had kerosene lamps and the galley fire (weather and cook permitting). There was no electricity for refrigeration. Fresh vegetables and fruit barely lasted out of sight of land. Potatoes were stored in the dark and given a haircut every week or so. Meat was “preserved” in casks of brine. Margarine came in tins. Coffee was drunk black. Even the water was rationed.

The boys were trainee officers – set apart from the sailors in the fo’c’sle and their masters in the saloon aft by virtue of being unpaid. They lived in the “half-deck”, an iron bunkhouse amidships, which on Monkbarns latterly consisted of two rooms and a corridor with doors either end so that entry could always be from the lee side of the ship while at sea. It was an ice box in the winter and an oven in the tropics, but it had a skylight exit and a “monkey bridge” to the poop that was popular in heavy seas, when the decks were often awash to a depth of two feet or more.

Monkbarns’ half-deck had bunks around the walls on three sides; a bare deal table with raised sides in the middle – flanked by boot-marked benches; a pot-bellied iron stove fed with coal filched from the cargo; and a battered cupboard in the corner divided into lockers, with fancy knotted rope tails for handles. There was a mirror, mottled with damp, and a single smelly kerosene lamp swinging in gimbals.

The bunks were narrow, with high boards along the open side to stop the sleeper rolling out as the ship pitched, and coloured pictures – often of girls, sometimes a country scene – pasted to the surrounding bulkhead by previous occupants. By some hung a canvas “tidy”, containing needles and cotton for repairs. The apprentices had to do all their own own mending, darning and cobbling. Laundry had to be done in salt water, in precious time off and only when there was chance of the garment drying.

New boys would arrive each trip with shop-smart dungarees and new straw mattresses, which the old hands in patched gear would regard balefully. Their own bunks were bare except for blankets, and within weeks the new boys learned why, when the “donkey’s breakfasts” had to be tossed overboard crawling with bed-bugs. Wet oilskins stayed wet, and chafing salt water boils were endemic.

Aboard Monkbarns “all modern appliances” did not include a donkey engine until the mid-1920s, and in many ports her cargo was loaded and discharged by hand – the boys shovelling Australian coal out through the hatches basket by basket to waiting lighters off the coast of Chile, until the dust grated in their lungs and ground itself under their skin. As the last basket was hoisted out there would be shanties and a well-earned tot of whisky – unless the Master was a teetotaller.

Then work would begin again, scouring out the filthy holds for the arrival of saltpetre, 200lbs a sack, which had to be swung aboard and stacked one by one in pyramids below. Monkbarns took about 3,000 tons, or 34,000 bags. The air would be like soup. Out in the Chilean anchorages, in holds lifting and falling in the long Pacific swell, the evaporation from the bags was known to kill rats and even woodlice, and ship’s cats would lie down in dark corners and not wake up.

Guano was considered worse, a throat-catching green powder of ancient bird droppings scraped off rocky outcrops further north, off Peru. But nowadays potassium nitrate is considered too dangerous to handle, let alone breathe.

Priwall – four-masted barque built by F. Laeisz of Hamburg for the nitrate trade – had steam winches and shore staff

The beautiful four and five- masted barques that set records and made fortunes for A.D. Bordes of Bordeaux and F. Laeisz of Hamburg shifted up to 5,500 tons of nitrates in eleven days flat, but they had steam winches – four to a hatch – and a small army of cadet officers and shore staff. Monkbarns did not.

Monkbarns boy Eugene Bainbridge, rowing around the bay visiting the other ships in Iquique in 1924, wrote enviously: “Priwall, which we went on next, was the antithesis of the Rhone, being spotlessly clean. She had every modern fitting – brace-winches (motor), halliard apparatus for two men to raise the halliards with ease, and a derrick on the jigger. Two wheels amidships with cable connection aft, where there are two more wheels under the poop. The Third Mate showed us the Captain’s saloon, decked up with light polished wood round the walls and carpet on the floor. She also carried plenty of spare spars etc. […] There was a bunk in the chart house for the Old Man, and a crowd of English charts used on the voyage round the Horn. We had a look at the log book, which registered one week nothing but 12 and 14 knots!”

Notwithstanding the rise of the oil industry by the 1920s, Corsar was not alone clinging to canvas in 1895. Many of the names familiar to us from the last days of sail were built after Monkbarns, including Penang and Pamir (both 1905), Peking and Passat (both 1911).

Laeisz had in fact only completed Priwall four years previously, in 1920, having been interrupted by the First World War. (In 1939 she arrived Valparaiso just in time to be trapped by the Second World War. She was interned, and 1941 was donated to the Chileans to avoid her falling into allied hands. Renamed Lautaro, she continued in the trade until she caught fire and burned out in 1945 while loading a cargo of nitrate off Peru.)

View of Valparaiso bay from Naval School. Ships left to right: Peru, Santiago, Monkbarns, Taltal, Queen of Scots (white hull) and Valparaiso in dock. Extreme left: barque California. E. Bainbridge collection

Though most sailing ships were less well equipped than the ships of the Flying P-line, they were still holding their own against steamers on the longer routes, to Chile and Australia, because of the price of coal – and the demand for sail-trained officers that would continue in motor-ships and oil tankers for many years to come.

Boys were cheap, British ships indentured them for four years largely unpaid and by 1919 (following a mutiny aboard) Monkbarns had expanded her deck housing to accommodate a dozen of them. They often made up half the crew. Steamers couldn’t afford to hang around, but sailers could. And hang around they did, for months at a time by the end, waiting for a charter.

Monkbarns left Valparaiso with her last cargo under sail in early 1926: a load of guano salvaged from another victim of Cape Horn, Queen of Scots. After they had sailed, the boys spent several days trimming the ship, wheeling the filthy stuff down the deck from the fore hold to the hatch aft. The ABs had refused, but the boys couldn’t.

As is recorded elsewhere, it was to be a weary voyage; Captain William Davies died – probably of stomach cancer – and they put into Rio, they were becalmed, suffered baffling winds and ran out of food.

They finally arrived in the Thames under tow after 170 days out and anchored off Gravesend, amazed at the sheer volume of traffic, big and small steamers passing in a continuous stream. Fresh meat and veg were delivered aboard and dinner that night was sausages and boiled potatoes.

“I can say that never was a meal so appreciated,” wrote young Bainbridge. The following morning they began heaving up the anchor at about 8.30am, to the shanty Rolling Home followed by Leave Her, Johnny, Leave Her, for the final leg to Charlton Buoys.

“All hands joined in with a will, even the pilot, so that the echo went ringing over the river and a large crowd gathered on the shore to listen,” wrote able seaman Dudley Turner in the fo’c’sle. “The pilot even grabbed a capstan bar and tramped around with us singing In Amsterdam There Lived a Maid.”

It was July 1926, and Monkbarns was the first full-rigged ship to come into the Port of London for eight years, “a wandering and lonely ghost which we may not see again,” wrote The Star. The Times called her “a picture out of the romantic past”.

Chips the ship’s carpenter was more prosaic. “I’ve had six meals since I came ashore 16 hours ago,” he told the Westminster Gazette, “and I’m still hungry.” Monkbarns was to find only one more cargo – Welsh coal, which she delivered under tow, to Norwegian whalers off Corcubion in northern Spain the following March. She finished her life as a coal hulk – the last British full-rigged ship to sail round Cape Horn, according to Alan Villiers (Sea-dogs of To-day, 1932), still bunkering passing steamers into the 1950s.

My last sighting is from a personal letter. Brian Watson, later senior pilot/deputy harbour master at Montrose, was then a nosy British steamship apprentice in the Baron Elibank. In 1954 he spotted a name in raised letters on the nearby bunkering hulk after his ship had sought refuge in Corcubion bay during bad weather. He recognised she was an old Britisher and climbed aboard for a look round.

In 1999 he wrote: “We berthed alongside a coal hulk and I could clearly see her name Monkbarns the metal letters still visible on her counter stern.” He said the masts had been cut down to stumps and he thought the bowsprit had been cut away, most of the deck and poop cabins had been stripped, a rusting galley stove had been moved into the poop accommodation.

Unfortunately, he was spotted by the steamer’s Mate and chased back to work before he could check the bows for the little white horse. The hunt continues for Corsar’s last figurehead with local help. More Watch this space – https://historiasdebarcosyveleros.blogspot.com

© Jay Sivell

This article has been amended since it appeared in The Cape Horner magazine, the journal of the International Association of Cape Horners. August 2014, V2 No 65

Next – Sniffing Stockholm Tar

Previously – In Remembrance: Save our Ships

Written by Jay Sivell

October 8, 2014 at 5:21 pm

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, Uncategorized, WWII

Tagged with apprentice, Cape Horners, first tripper, handelsmarine, John Stewart & Co, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, marina mercante, marine marchande, merchant navy, Monkbarns, Priwall, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, seamen's pay & conditions, square rigger, Tall ships, windjammer

A sailor’s life – 72. Death of a master, 1926. Monkbarns’ last trip

He was the teenage only son of well-to-do parents, with uncalloused hands and a yen for real life. Mother and Father – a marine insurance broker – were off on a world cruise for their health, so they packed him off on one of the last British windjammers.

And that was how Eugene Bainbridge, ex-Marlborough College, joined the motley crowd in the half deck of Monkbarns with his expensive Leica in Newcastle NSW in 1924 and set sail for two years on what would turn out to be the old square-rigger’s very last trip.

Bainbridge père paid £38 for Eugene’s third class berth out on the P&O passenger ship Barrabool – which was nearly five months’ pay for the men in Monkbarns’ fo’c’sle. John Stewart & Co apprentices, of course, as their indenture papers firmly stated, received “NIL”.

But even with half the hands working unpaid, the sums for the old windbags were no longer adding up. One by one, John Stewart’s fleet had been sold for scrap. Monkbarns was among the last four, and she had been laid up in Bruges for over a year until a lucky cargo of rock salt brought her out of retirement in 1923 one more time.

By Christmas 1925, she was in South America, in Chile, and the “boys” in the half deck saw in New Year 1926 stowing half a cargo of guano picked up from a derelict in Valparaiso bay – another old sailer that would never see Europe again.

Monkbarns at sea, October 1925 – Captain William Davies, Ian Russell AB at helm and ‘Sails’, Henry Robertson – private collection E. Bainbridge. “The Old Man went below to put on a clean collar”

They left in mid January, bound for home via the rough passage round the Horn. So far the voyage had already claimed two lives since the ship left Liverpool three years earlier – an apprentice lost overboard off one of the yards in a gale and a suicide by morphine overdose in Newcastle NSW – and now the master was dying of stomach cancer, but the seven apprentices didn’t know that.

Two days out of Valparaiso, Eugene wrote in the diary his dad had given him:

“23.1.26 Saturday. Washed half deck with John [Davies]. Took wheel 12-2pm. It struck me again what an advantageous point of view the wheel is. Everything puts on a more pleasing aspect as one views the quarter deck, and shipmates busy with some uninteresting job seem to hold an enviable position. The beautiful silence which reigns as you keep one eye on the weather leech of the top gallant sail. The sea is covered with little ripples today but would otherwise present a flat surface. The breeze is not bad, though considerably less than yesterday and the courses are drawing well. The breeze has dropped again but at 1.30 tonight it suddenly livened up and clouds appeared on the port quarter. Hall [seaman] came on to the lookout and started to talk about the copra trade before the high duties in Sydney. He said that it was on account of one or two fires that high duties were put on, and now there is no trade to speak of, the main bulk going to USA.

“24.1.26 Sunday. Oiled my second pair of oilskins and hung them out to dry. Turned in in the afternoon. Still making westerly and no sign of change.

“25.1.26 Monday. Finished chipping anchor chain and tarred some of it. Very little wind and still going to the westward. A fair wind (NW) is about the last thing that anyone would expect and we shall soon be in Australia like this!

“26.1.26 Tuesday. Wheel 8-10. Nothing to do but watch the sails. Wind gradually dying out and ship starting to roll slightly. Fine day and sun very strong. No clouds about. Wind disappeared and rolling at times. Finished the port anchor chain and lowered it into the locker. Hove starboard chain up on deck ready to scrape. Beautiful evening and Dave [cabin boy] joined me on the lookout from 8-9.30. I told him I wouldn’t be entertaining but he managed to get through a fair amount of talking, as usual, and was evidently satisfied. We discussed Goethe’s Faust, or at least, he did, and then he praised Scarlatti and Chopin.

“27.1.26 Wednesday. Flat calm and very hot (85 degrees in shade). Sleeping on main hatch where the night air is refreshing. Scraped the starboard anchor chain, tarred and stored it. This evening, the mate gave me a bucket to put a new rope handle on. I did it after referring to the book and put the usual “simple Mathew Walker” on. He praised them next day.

“28.1.26 Thursday. Flat calm and water like a sheet of glass. Saw big shark off the side of the ship but it went when we got the hook ready. It did not turn when it came to eat some offal which had been thrown overboard!! Started to trim the cargo in the forehold and taking it in barrow to the after hatch to dump. I had the job of standing by the hatch to tip the barrows. Played Langford [sailor] at chess. Slept out on the main hatch. Heavy dew. There are no apples or peaches in the ship, only prunes!”

For three weeks, as the ship made its way slowly out into the Pacific, the port and starboard watches chipped, tarred and stowed the mooring chains, and trimmed the cargo in the forehold, wheeling the stinking choking stuff barrow by barrow to the after hatch to dump. They reeved off new buntlines, downhauls, clewlines and braces. Chips made new blocks, and Eugene stood his trick at the wheel.

By the first week in February they’d swung SSE with the Easterlies and were heading for the Horn, the sea was becoming heavier and the skies had turned grey.

“6.2.26. The Old Man is bad today, and everything is done to stop the ship from rolling,” Eugene noted. “The mate changed course three times tonight for that reason.” In the half deck, a heavy tin of jam fell out of the apprentices’s locker onto Eugene’s head, inflicting damage.

“8.2.26 Monday. The atmosphere is the dampest that I have ever known and the horizon is blurred with mist. Sea and sky are grey alike and the wind from the northward is fairly strong, bringing with it a heavy swell. It was cold at the wheel at 12 o’clock today… The Old Man was a little better today and enjoyed a joke. The mate is very pale and together with overstrain and overwork has not slept for over 48 hours. No sights have been taken owing to the dullness but the mate took some stars last night. Lookouts are kept night and day and a sharp lookout for ice is to be kept. We are standing by all the time now, ready to attend brace or take in sail. When we were doing about 9-10 knots this afternoon and I was at the wheel a school of large Black Fish was keeping up with us. They jumped a little from the crests of the waves and could be seen black beneath the surface quite close. I should guess 12-14 feet would be their length and they had fairly pointed noses and a big thick dorsal fin.”

The temperature fell, day by day. “10.2.26. Wednesday. The temperature today was 45 degrees but it appeared to be much colder aloft and the steel yards stung when gripped. The old man is much better and cracking jokes.”