Posts Tagged ‘Newcastle NSW’

A sailor’s life – 80. Worse things happen at sea: the steward’s story

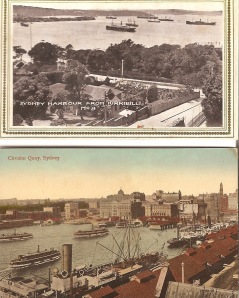

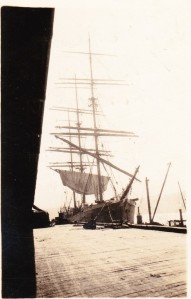

Monkbarns unloading nitrates in Walsh Bay No 10 Sydney, May 1925 (Copyright estate of Eugene Bainbridge)

David Morris called himself a journalist, a writer. He’d been on the lookout for a job on a square rigger for months before he heard of Monkbarns in Sydney in June 1925. He wanted “atmosphere” for some historical sea stories he was preparing to publish, he told the Newcastle Sun as the ship loaded Australian coal for South America. He wanted thrills, he wanted to “see the Pacific at its worst”.

Around him on deck, eyes slid away. “Some of the crew, with that superstition born in seamen, are inclined to regard him us a hoodoo,” the reporter noted.

Three weeks earlier Morris had shot across to Walsh Bay, Sydney, where the ship was discharging nitrate, and buttonholed the mate, offering himself in any capacity at a nominal wage. The mate had said “Nothing doing”, but as he trudged off down the gangway, they’d had a rethink. If he really wanted the experience, said the master, he could come along as a general helper at £2 a month (about £1,000 per annum today.)

Was it a cheap shot they’d expected him to refuse? Morris called himself the Captain’s steward, though he appears on the crew list as Cabin Boy, but pay for a seaman was £10 a month, not £2. Then again, as steward or “boy” he didn’t have to go aloft in all weathers or stand his trick at the wheel. He was a housekeeper, minding stores and dispensing first aid.

“Yesterday Morris was caught sewing his shirt, with stitches that would disgust a housewife, on the steps leading to the poop deck. He is a well-built man of 25, but he looks more like 30. The small moustache on his upper lip, and the tan shoes and the tweed suit already soiled by work in the galley, looked strangely out of place there,” said page 6 of the Newcastle Sun.

Movie poster for The Ship from Shanghai released in 1930 (http://adventures-of-the-blackgang.tumblr.com/

London-born Morris had visited most ports in the world as a passenger, and had slept in some of Australia’s best hotels and its least inviting parks in his quest for “atmosphere”, readers learned. He had been inspired to join Monkbarns by the runaway success of a sea thriller published the previous year by another young Australian journalist, Dale Collins. Ordeal is based on a round-the-world trip Collins made aboard the motor yacht Speejacks as historian to the US cement magnate Albert Younglove Gowen, who happened to be on his (second) honeymoon. The novel – about seamen turning on their idle rich passengers – was filmed in 1930 as The Ship from Shanghai, with Louis Wolheim as the ship’s crazed steward who holds them all hostage.

Morris was quite frank about what he was up to; there were men on Monkbarns who had had remarkable experiences, he told the newspaper, and he wanted to “chase up” some of those real-life stories. But he seems to have fallen short on listening. This may have been a world of horny-handed hard cases risking life and limb in all weathers aloft, but they still wouldn’t set sail on a Friday, or whistle for fear of challenging the wind, or even say “pig” out loud.

Of the 28 men and boys who had left Liverpool in March 1923, one was dead – a 19-year-old apprentice lost lashing down an escaping sail during a hurricane – two had been left behind in hospital injured, and two more would die before they dropped anchor back in the Thames in 1926.

Monkbarns 1923 securing lifeboats under heavy seas off the cape (probably photographed by 3rd mate Malcolm Bruce Glasier)

By June 1925, only the captain, the mate, “Sails”, a couple of ABs and the older apprentices remained of the original company. It was they who had faced down disaster on the passage out, when a hurricane south-west of Good Hope knocked them so badly that the cargo shifted. With the lee side of the ship 12ft under and green seas raking the deck, it was they who had risked their lives deep in the hold, shovelling rock salt uphill for three days to try to right her. Young Cyril Sebun was lost off the upper topgallant yardarm while they laboured. But nothing could have been done to save him. The boats were all smashed.

Eventually, they put into Cape Town in distress – a first for Captain William Davies. “During my forty years of service in sailing ships I have never had an experience that can in any way compare with this recent one, and to be quite frank, I should not like to pass through a similar ordeal again.”

On arrival in Australia, three seamen deserted – abandoning their pay – and Morris’s predecessor killed himself with an overdose of chloroform. He had been drinking heavily, the inquest noted. He was buried in Stockton NSW, where some of his former shipmates from the SS Argyllshire called the following spring. They sang Welsh hymns at his grave, and laid artificial flowers. They knew.

So, it was not surprising that Morris’ taste for ill winds made his shipmates uncomfortable and by the time Monkbarns had been at sea for two months, things had turned nasty.

Three entries from the diary kept by one of the apprentices, Eugene Bainbridge, offer a snapshot: 23.8.25. Sunday. Played Bridge all day and was 600 up to finish. It has been quite parky lately and it was anything but warm at the wheel from 12-2 tonight. Course ENE, on starboard tack. Shaved David Morris’s beard in half deck after putting him forcibly on the floor. He seemed a bit peevish and didn’t play ‘Vingt et un’ very well afterwards. The job we made of his beard wasn’t very good.

24.8.25. Monday. Clear, calm, sunny, fresh. Doing about 2-3 knots. Course ENE. ‘Maurice’ came in for about two minutes tonight. He seemed to know that there was something in the air and beat it.

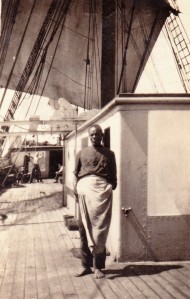

The Pelican Society photographed by Eugene Bainbridge – Newcastle-Callao 1925 (Copyright estate of Eugene Bainbridge)

25.8.25. Tuesday. A night of revelry of a peculiar sort. The subject was ‘Maurice Moscovich’. Notices were posted on the half deck doors inviting you to a singsong to be held in the fo’c’sle at 6.30pm. The Mate was particularly asked to refrain from blowing 2 whistles and when told why, was quite sympathetic. At 6.30 sharp, we met and the subject [Morris] had wandered into the gay party.

It was a bluff. He was to be seized in the middle of its proceedings and tried by the chief Pelican and his confederates. All passed off as planned and the victim was found guilty of not supplying the fo’c’sle with molasses and duly sentenced to have his port beard and starboard ‘tache shaved off. Cold water was used to emphasise the gravity of the act, and Bill Hughes, the Court Hairdresser, operated.

But worse was to come, because Morris evidently put up resistance to the assault, verbally if not physically. Bainbridge, a 21-year-old ex-boarding school boy from Maida Vale, London, records that the victim was deemed to have been “unduly insolent” to his tormentors – and a vote for death by dropping over the after part of the poop was passed.

Maurice Moscovitch as Shylock at the Royal Court, London, 1919 (From: http://exhibitions.europeana.eu/exhibits/show/yiddish-theatre-es/jml-las-obras/item/130)

It is possible that there was more than a little anti-Semitism in this “hazing” as Maurice Moscovitch was a well known Russian Jewish stage actor that summer wowing Australian audiences with his Merchant of Venice and Morris’s middle name was inscribed on the crew list as Isidor. Bainbridge had been to see Moscovitch at the Criterion theatre while Monkbarns was in Sydney.

More worrying still, the punishment meted out – for poor stewardship of the few treats that made the ship’s diet of salt meat and pulses bearable – apparently had the backing of the Master and the Mate. Bainbridge writes: We next trussed him up in a sack etc and took him aft for the mate’s inspection.

The procession marched solemnly back singing ‘For it’s a Lie’. Prisoner was next trussed up again (more securely) and taken forth to his execution. Maurice was marched up on to the fo’c’sle head and lowered away over the break. The wash tub was underneath and someone was making a noise like water. The stunt worked so far and when about a foot off the deck, the word was given and Maurice was dropped!!! He arrived in a heap at the side of the ‘donkey’ [steam winch] amid cheers and benedictions from the High Priest.

Had Morris believed his hostile playmates were actually dropping him gagged and bound into the Pacific? It seems more than possible, but he showed his mettle by joining them in the fo’c’sle, where proceedings continued as a “sing song”, and reciting a chunk of Kipling for the company. Whereupon everyone joined in a hearty chorus of “For he’s a jolly good fellow” and peace descended. Bainbridge wrote: The Old Man and Mate were both observed to be enjoying it uncommonly.

Many years later, “Bill the Court Hairdresser” – by then Captain William Hughes, sir – remembered David Morriss [sic] and his quest for atmosphere. “He got it all right, and I’m sure that what he went through before reaching London would fill two or three books,” he told AG Course, chronicling the history of the John Stewart ships for his book The Wheel’s Kick and The Wind’s Song.

View of Valparaiso harbour with Monkbarns marked by apprentice Eugene Bainbridge with an arrow at the bottom (copyright estate of Eugene Bainbridge)

Two months later, just outside Valparaiso, he was still annoying the apprentices (Dave joins us, and we are bored to a standstill with his platitudes!) but he’d graduated from ‘Maurice’ to Dave. And in port, Dave showed a pleasing openhandedness with the ship’s stores as the apprentices rowed around visiting and being visited by boys from neighbouring ships. (Dave got us some stores and there was plenty of scoff. He unfortunately spoilt this good turn by telling some of his tall yarns.)

However, as soon they put out to sea again and rationing restarted, the moans resume. 9.3.26. Dave wants to substitute sugar for molasses instead of substituting jam. This is not a fair exchange as sugar doesn’t go well with bread and butter! 5.5.26. Dave has been making mistakes with the weighing out of the butter and the tins containing so painfully small a quantity we complained and found we were getting less than our whack!

Happily, nine months after Morris’s sentencing by the Pelican Club, the horseplay had become rather more inclusive, if no less rough. By then, Captain William Davies was dead in Rio de Janeiro, the Mate was the new Old Man and the ceremony as Monkbarns passed Lat 0° 00’ 00” was a more or less welcome letting off steam after a very trying few months fighting their way round the Horn with the dying man refusing to put into port.

Young Bainbridge had a ringside seat. 9.5.26. Sunday. Crossed the Line last night. We all ‘felt the bump and noticed that the ship was going faster downhill!!’ At 1.30, I was let into the secret by Bill that we ‘offenders’ had to ‘go through it’. The Old Man had made some pills of ginger, glycerine and several other ingredients and covered them with sugar (of which there is a very large quantity aboard from Rio.) Jim had made some very ‘choice’ mixture of tar, tallow, soap, Melado (molasses) and red lead.

Monkbarns, Neptune’s court May 1926 – crossing the Line. Neptune and wife right, Dave Morris and Eugene Bainbridge among the tarred six on the left (copyright estate of Eugene Bainbridge)

In time honoured tradition, Neptune appeared over the side clad in oakum and bearing a huge trident made from the mast of the for’rard boat, accompanied by his Wife, his Barber, his Parson – in a lead foil cassock and paper collar – and his Doctor carrying the bag of pills. They set up court on the main hatch.

Bainbridge and Morris were among six “first trippers” the god of the sea wanted to inspect for fitness.

I was first blindfolded and then marched to the main hatch, falling over several ‘lines’ drawn across the deck. We had made the washhouse door fast and they had to break the handle off to get in. I was first asked by Neptune why I had done this and if I had crossed the Line before and why I hadn’t been ‘put through it’!

I then kissed his wife’s foot, which was covered with tar and was then shaved using the mixture, getting plenty of it in the mouth. I received the pills and spat them out. At a second shot, I managed to conceal one behind my tongue but before I could remove it my mouth was sore! I finished up being tipped backwards into a tub of water and then liberated. After I had seen two or three others done I went onto the boom and caught a 24lb bonito, which we had for tea. The proceedings broke up with all hands ‘splicing the main brace’.

They were back in the northern hemisphere after three years away, and “home” suddenly seemed closer. But Monkbarns’ adventures were not over. Progress was slow. Supplies ran out. By 450 miles off the Lizard they were down to rice and ersatz bread, but once into the shipping lanes an obliging German steamer provided relief.

They brought the boat alongside and the provisions pulled aboard: three sides of bacon, two hams, two cases of spuds, three sacks of flour and about 16 tins of Argentine boiled beef (we had some for tea and it was excellent), a certain amount of margarine and butter for the cabin, also lard and Dutch evaporated milk. Then the Cook gave us curry and rice for breakfast!!!!!!!! It was nearly the last of him.

But two weeks later they were still 12 miles off Portland Bill, and “reduced to rice, tea and a little jam and bread”, according to another unpublished diary of that voyage, by able seaman Dudley Turner. “Not had a smoke for weeks, which makes matters a lot worse.” And the Old Man was refusing to flag down any more ships.

When they picked up the pilot off Dungeness and it was discovered he handed out cigarettes for good steering – the first tobacco seen aboard for weeks – there was a rush to relieve the wheel frequently. “Never had such good steering been seen before by the old ship,” wrote Course. But they were so undernourished that the tug crew had to help them haul the hawser aboard.

At 6pm on 10 July 1926, Monkbarns dropped anchor off Tilbury. The pilot presented them with a sack of potatoes and Bainbridge records a “memorable feed of sausages and boiled spuds!!! Never was a meal so appreciated”.

The following day they were towed up to Charlton Buoys, a vessel from a bygone age gathering crowds on the banks, and there the crew were paid off.

And there the story ends. Monkbarns was sold “foreign”, and towed to Corcubion in northern Spain to end her days as a coal hulk. Eugene Bainbridge abandoned the apprenticeship for which his father had shelled out £42 and never went to sea again. What became of David Morris I cannot tell. Bill Hughes thought he’d gone in to radio in Melbourne. If he ever wrote up his historical sea stories, neither AG Course nor I could find a trace.

Bizarrely, the real thrill-seeker aboard Monkbarns that trip turned out to be the youngest apprentice, 17-year-old Len Marsland of Brisbane. After rounding the Horn in sail, in 1929 he pops up as a member of Sir Douglas Mawson’s Australian Antarctic expedition. He worked as a prison guard in Canada, chased the explorer Sir Hubert Wilkins across the Atlantic in an attempt to sign up for his submarine expedition under the polar ice, reappeared in Reykjavik, erecting a signal station, and then back at sea as an officer on an icebound freighter in the Baltic and facing down machineguns in a Russian Black Sea port. Tragically, Marsland’s adventurous career was short. While working as a stuntman for Sir Alan Cobham’s famous flying circus in 1935 his parachute failed to open. He fell 1,000 feet and died in Esher, Surrey, aged just 27.

Previously: A doctor aboard 1913

Written by Jay Sivell

May 29, 2016 at 12:39 pm

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Other stories, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, Uncategorized

Tagged with AG Course, apprentice, cabin boy, Captain Bill Hughes, Captain William Davies, Cyril Sebun, Dale Collins, David Isidor Morris, discipline and desertions, Eugene Bainbridge, first tripper, Frederick Leonard Marsland, handelsmarine, John Roberts, John Stewart & Co, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, marina mercante, marine marchande, Maurice Moscovitch, merchant navy, Newcastle NSW, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, seamen's pay & conditions, ship's steward, square rigger, SS Argyllshire, Tall ships, The Ship from Shanghai, Valparaiso, Walsh Bay Sydney, windjammer

A Sailor’s Life – 79. Doctor aboard (1913)

Tramping round the capstan, Monkbarns, by apprentice Eugene Bainbridge, 1924-26 (copyright: Estate of Eugene Bainbridge)

Much of what we know about the dying days of sail was recorded after the First World War, when most of Britain’s last old sailers had been sunk or ‘sold foreign‘.

Eric Newby’s The Last Grain Race and Elis Karlsson’s excellent Pully-haul were published as late as the 1950s and ‘60s, both about what were by then Finnish-owned vessels – the Moshulu, now a restaurant (!) in Philadelphia, and the Herzogin Cecilie, a wreck off Salcombe, Devon.

But in the summer of 1913, when the Liverpool-registered square rigger Monkbarns arrived off Australia from South America with a state-of-the-art Cinematograph movie camera provided by the Kineto film company of Wardour Street, London, “Everything that could be filmed about life aboard had been filmed,” the resident amateur cameraman noted.

Dr Dudley Stone was a keen yachtsman and junior doctor at St Bart’s hospital London who had joined Monkbarns in Gravesend that February determined to chronicle what was even then obviously the end of an era, from “swinging the ship” for correcting the compass before they sailed to the shanties round the capstan as they weighed anchor. His commission was to “obtain pictures of the ocean in its angry moods”. It was Kineto’s second attempt, after the chap it sent out the previous year had found himself vilely incapacitated by seasickness.

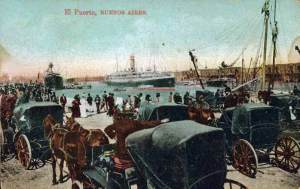

Over the months that followed, as Monkbarns crossed the Atlantic to Buenos Aires with a cargo of cement and then headed back eastwards in ballast round the Cape of Good Hope to Sydney, he shot 9,000 feet of film: of the men hauling and chipping, of the view from the yards, of big seas and the master in his oilskins. He developed it in his cabin and dried it all in strips festooned around a lazarette under the fo’c’sle head.

“I have cinematographed with no gloves and with oilskins and top boots on from aloft from almost everywhere.” Dating and developing it all had taken up to five hours a day, he wrote from Newcastle NSW.

Sadly, this nearly two miles of film seems to have disappeared. It is mentioned in the Australian newspapers of the time and was picked up years later by Captain “Algie” Course during the fireside yarns with fellow Cape Horners that formed the basis of his account of Monkbarns in The Wheel’s Kick and The Wind’s Song, but of the actual film there is no trace, not in the National Maritime Museum collection, nor the British Film Institute, nor the Australian Maritime Museum in Sydney. Shot from a heaving deck over 100 years ago, washed in saltwater, dried in a dusty locker and exposed to sulphur fumes when the ship was fumigated in Newcastle, it is unlikely any of it has survived.

Dr Stone’s unfinished diary, however, did survive – in the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich – and even without moving images it provides a rare glimpse of working life aboard one of the last British full-rigged ships a full 16 years before Alan Villiers and his ill-fated colleague Ronald Walker immortalised Grace Harwar, the last full rigger in the Australian trade.

Stone and his friend and patient, the Honourable John Gilbert Eveleigh-de Moleyns, aged 34, fifth son of the 4th Baron Ventry, were an odd couple aboard a working ship; de M’s condition is not identified but he lay down every afternoon, and usually played Euchre with the Mate for matches in the evenings or made quoits, which he played on deck when the weather permitted. Meanwhile, Stone was out along the yards or down the holds in all weathers with his Cinematograph, filming, or learning to take a noon sight and wrestling with calculations of the ship’s position and progress.

Neither did any actual work aboard, apart from “tailing on” occasionally.

But they roamed at will armed with a Videx Reflex and a Brownie, and Stone’s eye was keen. He noted the pilfering of stores by the ever-hungry apprentices, rough justice for a suspected thief who was given a hiding by his shipmates and booted ashore in Buenos Aires, and the stowaway “discovered” drinking tea in the fo’c’sle after they sailed. The Mate hadn’t known he was aboard, but the master did. Desertions had left him shorthanded. Two “stowaways” appeared after the ship had sailed, and both were entered on the articles at £1 per month.

Patrick Haggerty was an Irishman from Queenstown, Cork, red haired, blue eyed and popular. A fine shantyman, said Stone. He claimed to be off an Italian barque that had gone ashore near Buenos Aires and had only the dungarees, socks, cap and shoes he stood up in. After he was found half frozen at the wheel one night, the ship had a whip-round for him: the Mate gave him a shirt and an old oilskin, de M donated pants and socks, Stone rooted out an ancient spare jersey.

Stone’s surviving diary begins as they leave Buenos Aires.

A doctor was a familiar sight on passenger steamers, schmoozing the saloon crowd and keeping at bay any unpleasantness from steerage. Naval vessels too usually had a surgeon, to patch up battle injuries. But merchant ships knocking about the world with cargoes of nitrate or guano rarely enjoyed the luxury of trained medical assistance.

In the days of sail, physicking the crew was the responsibility of the “Old Man”, supported by a dog-eared copy of the Ship Captain’s Medical Guide and a case of pre-mixed bottles and papers labelled Solution No. 5 and Powder No. 3. Far from land, way off the steamer tracks and with no wireless to call for help or seek advice, the master had to rely on common sense and caution. Any ailment that didn’t involve actual blood loss was potentially malingering, and logs show intervention was rarely rushed. It is hardly surprising then that the presence of a bona fide doctor aboard Monkbarns was greeted with enthusiasm by her crew.

They set off from BA with all seven apprentices and three of the fo’c’sle down with diarrhoea, due to “the change of water”, the master diagnosed, and throughout what was to prove a very rough passage Dr Stone was kept busy.

Within a week storms were raking the ship. It was hard to sleep, wrote Stone. The main royal broke loose and tore both sheets out. The foresail ripped the starboard reefing jackstay clean off the yard, and the fore topmast staysail chafed most of the way through its bolt rope. In the store room all the pickles and a case of kerosene were lost. The following morning Stone watched the steward and two of the apprentices leaping about among the stores trying to catch tumbling tins. “Some had burst (I only hope they are the ‘blown’ ones I saw and that we will be saved from Ptomaine poisoning)”.

The fore hold was a jumble. There was rope everywhere, hanging over the edge of the ‘tween decks and tumbled below. The ship had acquired a list to starboard, and was rolling badly. The skipper had told him the squalls had been hurricane force 11 to 12, and that they might not have survived the night if the ship had been loaded. The boys’ half-deck had flooded.

Stone, who did not have to get up in the night to clamber aloft replacing blown-out sails, or sleep on a wet bunk in wet clothes, was amused to note that all the master’s drawers had shot out and his rug had spontaneously rolled itself up, but he was less pleased that the loss of the oil meant lights out at 9pm. There were only four candles aboard (his and de M.’s) and the ship was “badly found for matches”.

As paying passengers Stone and de M. occupied separate cabins in the saloon aft, with a porthole and two bunks each for all their gear. This left Leslie Beaver, the out-of-time apprentice acting 3rd mate, relegated to the lower bunk in the 2nd mate’s cabin.

“The Mate’s and 2nd mate’s cabins were like store rooms for nick-nacks and old rubbish. Their doors being opposite each other the contents of both cabins were well mixed. I just missed being hit by a camp stool paying a flying visit from 1st to 2nd’s quarters. Beaver had the much used water in their basin, the contents of a water jug and a tin of Swizo milk spilt into his bunk. He borrowed rug etc from de M. for night ”

More seriously, one of the ABs was injured. “Whole gale, hurricane squalls. Tremendous big NW Sea,” recorded the mate. “W Chapman knocked down and hurt.”

On June 7, Stone saw six “patients”, including Chapman, whose leg was skinned from knee to ankle. My own grandfather, then an apprentice of 18, sidled into the narrative with a tap at the doctor’s cabin door that evening. Stone noted an inflamed ligament, painful to the touch and prescribed iodine.

Captain James Donaldson was not pleased, though whether it was the molly-coddling or the lèse majesté is unclear. On June 11, Stone noted: “9.30 Went the rounds of the fo’c’sle at skipper’s invitation – a gentle hint that he does not like my going there on my own.”

Chapman’s raw leg was much better, a swollen knee was down and young Sivell was back at work again, against medical advice – (fed up with doing nothing, noted Stone.) Meanwhile, there was a strained shoulder to inspect (“nil to be seen. I’m safe…”), and the 3rd Mate had been shot into the scuppers on his stomach during a particularly heavy roll, resulting in appalling bruises but fortunately no internal injuries.

And still the glass continued to fall, down to 28.58. The fore lower topsail carried away.

At 3.30am, on a page labelled Hurricane, Stone recorded: “Broached to on port tack – my top row of bookshelf showered its contents on my head and then continued across cabin. Got up and collected them. 4 Very heavy squall carried away fore topmast staysails and new No 1 canvas sail. 7 de M came over to me and I produced LGCL book on meteorology and we tried to make out what position we were in with not much success. 7.30 Hot coffee went the rounds. 8 Broached to on port – more things going to leeward – thank goodness the ballast remains a fixture. This is as heavy a blow as any of ship’s officers have been in. I certainly cannot imagine more wind or a bigger sea. I heard that at 3.30am the 2nd mate and a hand went aloft to see to upper fore topsail and that on coming down he stepped into lee scuppers, which were full up with water. He is a short fellow and was up to his neck. That I think gives me some idea of the sea shipped on broaching to, and we in ballast.”

The Old Man – who was 64 and had been up all night – was laid up with cramp in the chart house, and the foremast staysail was a rag.

The hurricane squalls and strong gales continued for three weeks, almost without let up. Stone and de M. would tell the newspaper reporters waiting in Newcastle that they were both “ardent lovers of the sea” but neither of them ever wished to undergo such an experience again.

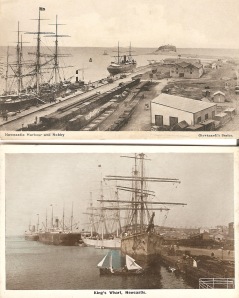

Monkbarns was one of five sailing vessels that arrived at Newcastle on the weekend of 5th July 1913, including the full-rigged Ben Lee, which had sailed from Buenos Aires two weeks before her. All had suffered. Ben Lee’s lower topsail had carried away and the foresail was blown to pieces. Kilmallie, from Santos, lost a lifeboat and her ballast shifted. The barque Lysglimt, from Natal, was knocked onto her beam ends when her ballast shifted, and the crew spent three death-defying days in the hold trying to right her, the Sydney Morning Herald reported.

Despite or possibly thanks to the hurricane, Monkbarns had made the passage in 52 days, to Ben Lee’s 67. Our man on the docks reported that two of Monkbarns’ crew had been injured and had been “attended by Dr M Stone, a passenger”.

Up in Newcastle, (where they went because there was smallpox in Sydney and the city was about to be quarantined), the Newcastle Morning Herald & Miners’ Advocate produced a much juicier report, headlined “An interesting visitor”.

Dr Stone, it said, had been imprisoned by Germany for spying the previous year (shades of Erskine Childers‘ The Riddle of the Sands). Dr Stone did not deny it. He had been one of a party of five well-to-do British yachtsmen – including the marine artist Gregory Robinson and the engineer William Richard Macdonald, who happened to have patented a nifty bit of submarine technology. They had attracted unwelcome attention from the German military authorities by happily photographing naval installations along the Kiel canal. It had taken them five days to talk themselves out of jail.

During the war that broke out less than a year after Monkbarns’ arrival in Newcastle, Stone would serve in the Royal Army Medical Corps. He became an eminent radiographer, with an obituary in the British Medical Journal in 1941.

The Kineto company, however, folded in 1923 and de M died in New Zealand in 1928, the year after Monkbarns was hulked off Corcubion, in northern Spain.

Stone carried on yachting all this life. Perhaps he even shot more films. But what became of his footage of working life aboard a British ship in the last days of sail remains a mystery.

*

An edited version of this article appeared first in The Cape Horner magazine, the journal of the International Association of Cape Horners. August 2015.

Photographs by Eugene Bainbridge, who was Monkbarns’ last apprentice during her final voyage, 1924-26. He joined her in Newcastle NSW, having steamed out from the UK third class aboard the P&O passenger ship Barrabool. He was then 19, the privately educated only son of a maritime insurance broker from Surrey. He had a Leica camera and for two years he kept a diary and took pictures of life aboard. Neither the diary nor the photographs were ever published and Eugene never went back to sea. These previously unseen views are made available by kind permission of his family.

Next: Worse things happen at sea

Previously – Flowers in Hong Kong, Medals in the Post iii

Read from the start:

A sailor’s life – beginning, middle and end

Written by Jay Sivell

May 8, 2016 at 2:10 pm

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Historical postcards, Isle of Wight & Sivell family, Other stories, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, Uncategorized, WWI

Tagged with apprentice, Ben Lee, Bert Sivell, Captain James Donaldson, Cinematograph, Dudley Macauley Stone, Eugene Bainbridge, handelsmarine, health at sea, injuries in sail, Isle of Wight & Sivell family, John Gilbert Eveleigh-de Moleyns, John Stewart & Co, Kilmallie, koopvaardij, last days of sail, Leslie Beaver, life at sea, Lysglimt, marina mercante, marine marchande, merchant navy, Newcastle NSW, passengers on sailing ships, seamen's pay & conditions, square rigger, storms at sea, Tall ships, unpublished footage of sea, Videx, William Chapman, windjammer

A sailor’s life – 45. A boy’s own story

Nothing much seemed to have changed when Monkbarns limped back into Newcastle NSW in November 1920 with a new captain and a broken mast.

The Monkbarns boys were given the afternoon off to hear a concert at the Mission, and for most of the next month they had time off in the evenings and at weekends to lounge about the beach, surfing, playing tennis and making up tea parties, while they waited for the repairs. Captain Davies of Nefyn was welcomed like long-lost son by Newcastle’s Welsh mayor, Mr Morgan, and there were “umpteen” other sailing ships in port, including Vimeira, Garthsnaid, Kirkcudbrightshire and Rona (- now possibly better known as Polly Woodside), with 37 apprentices between them. On November 5th and 6th apprentice Francis Kirk wrote just two words lengthways down an entire page of the schoolboy notes he kept that trip: “Enjoying life”.

On the 20th Monkbarns hosted a dance, with more than fifty girls, he recorded happily. The old ship looked fine, decked out with flags and Chinese lanterns, and “our famous jazz orchestra” had played selections during the evening. They were still in Australia at Christmas, which Kirk celebrated in Lambton with the Blanch family, and they saw New Year in with a big regatta in the harbour at which the Monkbarns “men” won £5 in one of the races. On January 9th 1921, they left Newcastle again bound for South America, “with heavy and breaking hearts”, Kirk scrawled, “All the girls gathered on Nobby’s Head and waved the old ship out of sight…”

Kirk, like Bert Sivell, had eventually left sailing ships for oil tankers, but he had never got over his love of the old square-rigger.

In 1957 he became one of the first members of the new British branch of the Amicale Internationale des Capitaines au Long Cours Cap Horniers – or Cape Horners’ Association – originally founded in St Malo, France, in 1937 to “promote and strengthen the ties of comradeship which bind together the unique body of men and women who enjoy the distinction of having voyaged round Cape Horn under sail”. They were “albatrosses” (who had commanded a sailing vessel round Cape Horn), “mollyhawks” (served in a sailing vessel round Cape Horn and subsequently commanded a motor ship), or “cape pigeons” (cooks, stewards, passengers etc).

Kirk – ranked Mollyhawk – threw himself with gusto into the annual jaunts to St Malo or Hamburg, Oslo or later Mariehamn, which held the record for old Cape Horners. “He used to come back with pictures of him and ‘old so-and-so’ and usually a woman in the shot whom he would pass off as such-and-such’s wife,” said his son. After his death there had been several intriguing lady callers.

In the 1960s an English language journal was set up, The Cape Horner, and its editor, Captain AG Course – UK member 9, wrote that if any member was in Bournemouth, they were welcome to join the members’ coffee mornings, every Friday at 10.30am in Bealson’s cafe on Commercial Road. “No advance notice is necessary and your wives, relatives and friends will be welcome. Only one wife at a time, please!”

The maritime author Alan Villiers wrote of joining one of these coffee mornings in 1971, and meeting “eight wonderful old boys, most of them octogenarians, except one aged 92, all with the stamp of the sea still upon their open faces, the snap of command in the old blue eyes”. The “wonderful old boys” more generally were not uniformly impressed by the new boys’ patronage (“… not really a proper sailor…”), and the subsequent acceptance of yachtsmen as Cape Horners when anno domini began to tell on the original pre-motor, pre-GPS membership was contentious.

I was too late to meet Francis Kirk, or Harry Fountain, Victor Fall, Lewis Watkins, Lionel Walker and “Algie” Course – who single-handedly salvaged most of what is known of Monkbarns’ history, mainly by running his finger down the UK Cape Horners’ membership list and calling the old shipmates in for a fireside chat. (Which accounts for some of the more lurid tales). But their lives still resonate down the generations in remembered stories (“He said the freezing flailing canvas ripped fingernails to the quick…” “you tapped the biscuit on the table to knock the weevils out…”), and dusty diaries and yellowing photos, providing a lasting testament to all those boys like my grandfather who went down to the sea in ships and did business in great waters in the last days of sail.

Coming next: A model ship

Previously: Goodbye, Monkbarns – Corcubion, 1954

*

Sea Fever

I must go down to the seas again, to the lonely sea and the sky,

And all I ask is a tall ship and a star to steer her by,

And the wheel’s kick and the wind’s song and the white sail’s shaking,

And a grey mist on the sea’s face and a grey dawn breaking.

I must go down to the seas again, for the call of the running tide

Is a wild call and a clear call that may not be denied;

And all I ask is a windy day with the white clouds flying,

And the flung spray and the blown spume, and the sea-gulls crying.

I must go down to the seas again, to the vagrant gypsy life,

To the gull’s way and the whale’s way where the wind’s like a whetted knife;

And all I ask is a merry yarn from a laughing fellow-rover,

And quiet sleep and a sweet dream when the long trick’s over.

John Masefield 1902

Written by Jay Sivell

November 4, 2010 at 3:03 pm

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice

Tagged with AG Course, Alan Villiers, apprentice, Bert Sivell, Cape Horners' Association, Garthsnaid, handelsmarine, Harry Fountain, John Masefield, John Stewart & Co, Kirkcudbrightshire, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, Lionel Walker, marina mercante, marine marchande, merchant navy, Newcastle NSW, Polly Woodside, Rona, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, Sea Fever poem, square rigger, Tall ships, Victor Fall, Vimeira, windjammer

A sailor’s life – 41. A face in the crowd

As the world celebrated the end of the war in November 1918 with dancing and concerts, old “Jock” Donaldson, master of the British sailing ship Monkbarns far from home in Bunbury WA, put his feet up in the town’s best hotel and sat back to await the arrival of the Melbourne steamer SS Kurnalpi, and his son.

James Donaldson jnr, born like his father in West Kilbride, Scotland, within sight of Portincross Castle – from where the bodies of Scotland’s kings were ferried to Iona – had followed the Old Man to sea and in 1908 joined the Melbourne Steamship Co, tramping the west Australian route from Perth to Sydney, £14 return in saloon class.

By 1918 he was Captain Donaldson, 39, with a wife and children, and a ship of his own, and that November his regular call at Bunbury would coincide with Monkbarns’ time in port. So, while Bert Sivell and the 2nd mate oversaw the apprentices discharging the slimy ballast stones loaded in Rio de Janeiro and the scouring of the holds and the killing of the rats (at which young Cobner was to prove a dab hand) and the laying of dunnage for the consignment of Jarrah wood railway sleepers due to arrive any day from the sawmill inland, Captain Donaldson took up residence in the Rose hotel, yarned with the mayor and his cronies, and waited.

“One day there was great excitement on the ship,” wrote apprentice Victor Fall. “For weeks the Old Man had been talking of his son, and his steamer. The apprentices in particular were anxious to see this ship, as from the Old Man’s account she was at least equal to the Katoomba, the 10,000-ton interstate liner.

“At last, a very small steamer about 250 tons came into the bay, belching black smoke from a tall funnel, which seemed too big for the ship. She was so small that as she passed the stone breakwater only the top of her masts and funnel were visible.” Memory is an unreliable witness – Kurnalpi was in fact a 495 tonner, twice as big as Fall remembered, but the Monkbarns boys were not impressed. ‘THAT thing, we could swing her on our davits!’ one of them was heard to remark, rather regrettably within the Old Man’s earshot, Fall recalled.

Meanwhile, among the mayor’s wife and her circle, interest focused not on Kurnalpi but on the tidbit that Captain Donaldson was also expecting the arrival of his daughter from Melbourne, and the grandchild he hardly knew, supposedly a little girl of nine.

On November 24th 1918 a series of photographs was taken on and around Monkbarns, two of which featuring – if reluctantly – the 70-year-old captain. (“The old man is looking pretty fierce. I had a fine job getting him to come out” wrote Bert.)

Bert himself is there, seated beside Donaldson, awkwardly showcasing the three stripes on his sleeves. Victor Fall is there, and Lewis Watkins and Percy Wilkins – who later married an Ozzie girl in Newcastle NSW and is believed to have carved out a career for himself in state politics. The rat-catcher James Cobner may in the photo too. He also settled in Newcastle NSW, and opened a chain of drycleaners. But the central face in the photo is a mystery.

I think it is Donaldson’s grandchild. You guessed, another James Donaldson.

*

In the photograph: Captain Donaldson and First Officer Bert Sivell, seated; ranged behind them from left – unknown, unknown, Malcolm Glasier (15) with cane?, unknown, 2nd Mate Gilbert Cheetham? holding child, unknown, Percy Wilkins (19), Victor Fall (17), Lewis Watkins (18) and unknown.

Next: Shanghaied, and a death at sea

Previously: Armistice in Bunbury WA

Work in progress: the book I never wrote about the sailor grandfather I never knew, from his apprenticeship on the square-rigger Monkbarns to his death by U97, presumed lost with all hands aboard the Shell oil tanker Chama in 1941 Blogroll

Written by Jay Sivell

August 11, 2010 at 6:03 pm

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, WWI

Tagged with apprentice, Bert Sivell, Bunbury, Captain James Donaldson, handelsmarine, John Stewart & Co, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, marina mercante, marine marchande, merchant navy, Newcastle NSW, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, square rigger, SS Kurnalpi, Tall ships, Victor Fall, Western Australia, windjammer

A sailor’s life – 38. A walk among the spars

Monkbarns apprentice Victor George Fall, July 1918, aged 16, from the collection of John Fall, Australia

“One after another the new apprentices swung into the shrouds and, slowly at first, mounted the ratlines until they reached the futtock-shrouds to the ‘top,’ a small platform at the top of the lower mast,” wrote former Monkbarns apprentice Victor Fall, years later.

He and nine other teenagers had been posted out to Brazil from Britain after the infamous mutiny around the Horn in June 1918. They joined the ship in Rio de Janeiro in September and on their first afternoon aboard, the young chief officer, Bert Sivell, gave them permission to go aloft.

“The futtock shrouds, like a small ladder, project outwards from the mast, so one has to climb more or less on one’s back – like a fly on the ceiling – until one has got over the edge. Rather an ordeal for a new hand. Then, glowing with a sense of achievement, you can pause and look around. Just below was the huge main yard, 92ft long and weighing three tons, supported by lifts and a big steel hook and held to the lower mast by a metal band, allowing it to be swung fore or aft by ‘braces’ from the deck below through a tackle at the yard arms.

"Climbing like a fly on the ceiling" - the futtock shrouds to the 'tops' (Photograph: squarerigsailing.com)

“Strung below the yard on wire strops was the footrope, on which men stood when laid-out on the yard furling or reefing the sail. Along the top of the yard ran a steel rail, with wire ‘grommets’ at intervals, rather like large coits; through them an arm could be thrust in time of need,” remembered Fall.

Below on deck figures moved to and fro doing incomprehensible things; on the dockside locomotives fussed about shunting trucks, while beyond lay the blue water, the islands and the anchored ships. It was all rather pleasant, but this was really only the start of the climb.

“From the top, on either side of the mast were narrow, nearly vertical wire ladders, the topmast shrouds, which led to the topmast cross-trees. On the way up you passed the huge spar of the lower topsail yard, and just above it, supported by wire lifts and held to the mast by a metal parral, the upper topsail yard. This was hoisted when the sail was set, rising another thirty feet above the yard below.

“On reaching the cross-trees, the climb was still not nearly done, as from them ran upwards another ladder, quite vertical this time, leading to the head of the topgallant mast. On this mast were two more yards, positioned much as the larger topsails below. Above the topgallant masthead the mast rose for another 35 feet to the royal yard. When the royal yard was hoisted and sail set the only way to reach this was by climbing, hand over hand, up the iron chain of the royal halyards, until you could swing a leg over the royal yard and site astride it, or stand on the footrope.

“To reach the absolute top of the mast – the truck – required a hand over hand climb. However, even when lowered, the royal yard was about 150ft up, and the view was marvellous. The men below were tiny figures, the locomotives toys, while the wider view stretched right across the harbour.”

Monkbarns new apprentices were pleased with themselves. They, who had never been away from home before, had travelled across the Atlantic in armed convoy, and now they’d been right up the main mast to the royal yard.

“Soon they would be going up and down, day or night, as a matter of routine,” wrote Fall. “Barefoot most of the time, but in heavy weather in clumsy sea boots and oilskins. ”

On this first attempt, the boys had descended with care, finding coming down more difficult than going up, and had arrived back on deck with an “ill-concealed air of pride”.

*

Next day the “business of the sea” which John Stewart & Co had promised to teach each of them started in earnest, as they were set to work washing down decks, coiling gear, and helping “bend on sail” – hoisting the heavy canvas from the deck to its appropriate yard, sidling along the yards on the footropes and then learning how to lash the sails to the jackstay and pass rope gaskets around them for a neat stow. Then, there were halyards to reeve and buntlines.

After three days of this, Monkbarns was towed out of drydock and lighters came alongside with stones for the ballast. The stones were swung aboard in baskets and tipped down the hatches. John Stewart & Co didn’t do engines – the boys believed there had been one ill-fated experiment in the past, after which the old sailing ship captain had banned them – so down in the steamy holds the apprentices sweated, dragging the slimy stones out to the sides, balancing the ship, shovelling the smaller stuff till their hands blistered.

After three more days of that – broken only by a spell on deck sending aloft the cro’jack yard, which had been ashore for repairs – there were sails to be bent on until every yard had its canvas aloft and they were all ready to set sail.

Now the 3rd Mate went to fetch the Old Man from shore, and returned with the news that the ship had a charter for Bunbury, in Western Australia, to load jarrah wood.

The boys and the young mates looked at each other. Nobody had heard of Bunbury. They were disappointed that they weren’t going to Newcastle, NSW, where there were lots of ships and girls and parties. “There was much searching of atlases,” wrote Fall.

He didn’t know it, but he was about to emigrate.

From: One Cargo of Jarrah, by VG Fall

Next: Fishing for albatross

Previous: The new boys arrive in Rio

Written by Jay Sivell

July 28, 2010 at 8:04 am

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, Sailing ship mutiny, WWI

Tagged with apprentice, Bunbury, futtock, handelsmarine, John Stewart & Co, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, marina mercante, marine marchande, merchant navy, Mutiny, Newcastle NSW, ratlines, royal yards, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, Sails and rigging, shrouds, square rigger, Victor Fall, war at sea, Western Australia, windjammer

A sailor’s life – 23. Deserters, stowaways & sailing to war, 1914

Dr Johnson, from James Boswell’s The Life of Samuel Johnson

Bert Sivell celebrated his 18th birthday in spring 1913 in Buenos Aires, surrounded by steam ships and bustle and electricity, unloading cement from Greenhithe, London, after 61 days at sea in an ill-lit, unheated square rigged sailing ship – cold, wet, uncomfortable and in Bert’s case, unpaid.

In Buenos Aires, with orders to sail for Australia, Donaldson was struggling. The ship’s papers specified a minimum number of hands needed to work the ship, so the loss of six left him badly short, even after the missing cook was carried back aboard, dead drunk. And then by a stroke of luck, while the ship idled expensively at anchor in the River Plate, two “stowaways” were allegedly discovered. The Old Man didn’t mess about. Both were promptly entered on the articles at £1 per month, and the ship sailed.

Three months later, in Newcastle NSW, six more men deserted – including the drunken cook. In fact, Asklund recalled, the fo’c’sle emptied, apart from him and two Finnish able seamen. The cook was owed £2 5s 2d, according to the log, but desertions in Australia were considered inevitable because coasting vessels there paid more than the British sailing ships passing through.

Monkbarns spent two months in Newcastle, loading coal, and hunting for crew. There were several British sailing ships in port, including John Stewart & Co’s Lorton, and Monkbarns’ twin Belford, and lots of lads stumbling among the bales and rails along the Dyke at home time. Asklund remembered the Reverend Forster Haire belting out My Old Shako at the mission concerts and Bert sent dozens of postcards showing the Reserve, where they walked, and the beach, where they lolled, and the kippered buildings along the steam tram line in Scott Street. He also sent one of Belford, highlighting his own ship’s superior points.

In the half deck the shortage of hands was felt acutely. Bert recorded that one night the callow mate — himself an out-of-time apprentice — had tried to stop the boys going ashore, to have them on standby to shift the ship off the loading Dyke. “Of course, we objected to that,” Bert wrote. “So we all dressed and all eight of us and our young Swede walked sedately over the gang-way. As we walked back along the Dyke at 10pm in a body we saw the old man and mate talking, so it was look out for trouble. But to our surprise nothing happened. They were waiting for us. It appears that the mate had tried to stop us on his own without the old man’s knowledge. We had been working hard since 3am that morning and it was past midnight before we finished. “

From Newcastle they sailed for Chile, to pick up saltpetre for Durban, South Africa, and from Durban they sailed in ballast – that is empty – back to Australia, arriving nine months after they had left, with another stowaway who had been made to work his passage. In Sydney, four men deserted and two who signed on failed to join. The ship’s boy decided to join the navy. A postcard view of Sydney harbour, strangely bald to modern eyes without the harbour bridge and the opera house, records that Bert and another apprentice took an hour and twenty minutes hard rowing to get the Old Man ashore in the teeth of a southerly gale. They were loading for Chile again, seed wheat this time, and “working like niggers” [sic] he complained. But he “rowed the ladies about” and made friends at the Mission.

They left Australia in early June 1914 and were out in the southern Pacific cut off from everything except the sea and the sky when a young Serb nationalist in Sarajevo shot dead the heir to the Austro-Hungarian empire.

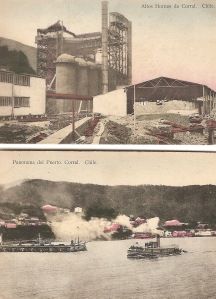

By the time Monkbarns dropped anchor in Corral, on the west coast of Chile, in the second week of August, war was erupting across Europe and beyond like firecrackers. In Monkbarns’ half deck the focus was on business as usual. The fighting was expected be over by Christmas, and Monkbarns would not be off the Lizard, in Cornwall, until the following April at the earliest.

The log records daily lifeboat drills, which was new, and five apprentices were promoted to able seamen, but the ship had been in Chile for two months before Captain Donaldson and “H. Horstmeyer, German,” decided it might be better if the now enemy member of Monkbarns crew were discharged. Even then, Horstmeyer’s wages were properly calculated and paid to the consulate in Valdivia.

“Just a card to let you see that the Germans have not caught us yet,” Bert wrote casually from Corral to his Ma on a view of iron ore smelters. (“Needless to say closed, due to lack of funds.”) Chile was technically neutral, despite its large German community, and his main topic was not the war but a dispute with the owners of the ore works who were claiming 1,000 pesos, or £29, for Donaldson having put a line on their jetty to avoid a collision. It was also raining, he reported.

But war was about to come to the nitrate lanes.

Read on: Monkbarns and the Battle of Coronel

Previously: The nitrate coast, Chile, 1912

Work in progress: the book I never wrote about the sailor grandfather I never knew, from his apprenticeship on the square-rigger Monkbarns to his death by U97, presumed lost with all hands aboard the Shell oil tanker Chama in 1941 Blogroll

Written by Jay Sivell

June 16, 2010 at 6:20 am

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Historical postcards, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, WWI

Tagged with apprentice, Buenos Aires, Captain James Donaldson, desertions, discipline and desertions, handelsmarine, John Stewart & Co, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, marina mercante, marine marchande, merchant navy, Newcastle NSW, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, square rigger, Sydney, war at sea, windjammer

A sailor’s life – 21. Monkbarns apprentice: Harry Fountain

There was a new crop of apprentice boys in the tin bunkhouse amidships by the time Monkbarns arrived back in Newcastle NSW, Australia, in November 1920, after the end of first world war; new faces in the patchy mirror on the bulkhead and new views of “home” pasted to the walls of each narrow bunk. Many of the old sailing ships had been lost, but not “lucky” Monkbarns.

There were four other British square riggers in port too, they remembered, with 37 apprentices between them, plus boys from the French Champagne and Danish Viking. The Monkbarns apprentices were given the afternoon off to hear a concert at the Seamen’s Mission in Stockton and for most of the next month had time off to lounge about the beach, play tennis and go on picnics with the pretty girls, while they waited for repairs to one of the masts.

“We made our own amusement,” wrote Harry Fountain, in The Cape Horner magazine. “There was probably a theatre, there must certainly have been picture houses, but they were ever beyond us with our few pence. I seem to remember that was soon spent in the Niagara Café on banana splits at 9d a plate.”

Captain Harry Fountain, one of many dozens of boys who passed through Monkbarns’ half deck over the years, served the sea all his life and lived to the ripe old age of 95. What became of “Tich” Copner, Reg Bannister (“who snored like hell”) and the Belgian, Marcel Emil Brough, I never discovered, but Fountain never lost touch with his old shipmate Lionel Walker, who had settled on the other side of the world with the Aussie mission girl he had gone back to find.

Jessie Walker’s family gave me his last known address when I traced them – a damn fool Pom grandchild still doggedly hunting witness accounts of life on Monkbarns three-quarters of a century later – and with typical generosity they heaped on me newspaper cuttings and photographs of the charabanc trips and tennis parties. But my letter to Harry in Boston, Lincolnshire, was returned by his executors: Captain Fountain, retired harbour pilot and sometime pub landlord, was finally at rest under the handsome headstone he had bought and gleefully visited for many years on his daily walk to the docks. He told his local paper the secret of his longevity had been cold showers, bread and dripping, and 20 Senior Service cigarettes a day.

The solicitor put me in touch with one of the old man’s friends. “He would have loved to have talked to you,” they both said. I had missed him by four months.

Read on: The nitrate coast, Chile, 1912

Previously: Pommie boys and Aussie girls, Newcastle NSW 1912

Written by Jay Sivell

June 13, 2010 at 4:23 pm

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Other stories, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice

Tagged with apprentice, first tripper, handelsmarine, Harry Fountain, John Stewart & Co, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, Lionel Walker, marina mercante, marine marchande, merchant navy, Newcastle NSW, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, square rigger, windjammer

A sailor’s life – 20. Pommie boys and Aussie girls, Newcastle NSW 1912

Monkbarns from Nobby's head, Stockton NSW, Australia - the photograph Jessie Walker kept on her wall all her life

From Hamburg that first trip, Monkbarns circled the globe, sailing first across the Atlantic with the north-east trade winds and down the east coast of South America to Santos in Brazil; then south-east through the Roaring Forties and round the Cape of Good Hope to continue in the prevailing westerly winds across the Southern Oceans to Australia. From there, after two months, they moved on eastwards across the Pacific to Taltal on the west coast of South America in Chile, before rounding the vicious Cape Horn backed by the westerly gales again, bound for home.

From Millwall, on the Thames in London, Bert Sivell scribbled a postcard to his pa on December 6th 1912: “Please write soon.” He had been away for a year and four months.

But the log shows the ship had been at sea for only half that – leaving long days in each port while the Old Man struggled to hang onto enough men to work the ship. In Santos, two of the Danes and the Austrian deserted, and after 66 days at sea the boys enjoyed six weeks dallying round the anchorage on the edge of the forest. “Fine bathing here,” Bert wrote.

Monkbarns boys and a Mission charabanc outing, Stockton NSW. Private collection of the Walker family, Australia

In Newcastle NSW, three months at sea later, two more men crept off the ship never to return, and Monkbarns’ log begins to lengthen with Captain Donaldson’s attempts to maintain discipline. Wages in the Australian coastal trade were temptingly higher than anything he could afford to pay, with fewer gales and icebergs.

For the boys, the painting, cleaning and mending continued from 6am till 6pm. Time off ashore (“Liberty” days) were at the Master’s discretion, particularly in South America, where there was a danger of Yellow Fever. But there was usually plenty for the boys to see, even at anchor in the roads, and rowing the officers about was one of the apprentices’ more welcome chores. They had to wait by the boat, rather than go into town, but there were usually work boats from other ships tied up there too and other boys to “yarn” with. Every day brought new arrivals and departures among the thicket of masts.

In Newcastle, Australia, however, beside the picture house and other luxuries beyond an apprentice’s pocket, there was also a lively Seamen’s Mission on the riverfront at Stockton. With a steam launch to pick up all comers, and an army of hospitable volunteers, the Reverend Forster Haire laid on free Sunday teas and concerts and charabanc trips for the visiting sailors. There was dancing, and magic lantern shows — as well as the church services, which the ungrateful young pups ducked out of wherever possible.

In Stockton, big-hearted families who had never seen Europe held open house for apprentice boys from “the old country” with roast beef and Yorkshire pudding, and their tender-hearted daughters lined the breakwater to sob goodbye when they sailed. “Some days you couldn’t get on the breakwater for girls waving goodbye,” recalled Jessie Walker, a former Mission girl, aged 92, tracked down through the library there. Girls wishing to help entertain the sailors were interviewed for suitability, said Mrs Walker.

Jessie herself had married a Monkbarns boy who turned up back on her parents’ doorstep in 1924, blinded in one eye by ice round the Cape. In the nursing home in the converted mission building in Stockton where she ended her days, surrounded by her children and grandchildren and great grandchildren, a photograph of Monkbarns still took pride of place on the wall. Framed against a gathering storm, the ship is frozen in time heading out to sea off Nobby’s Head, where the bonny girls were still waving. Two tiny figures can be glimpsed high up on her yards, busy releasing the sails.

I never met Jessie Walker, or her family, but I can vouch that their generosity and hospitality remained undimmed three-quarters of a century later when I wrote asking for information.

Bert spent two months in Australia in spring 1912, sending home dozens of annotated postcard views of Newcastle and Stockton and a photograph of what looks like himself, sitting among the crowd at the old “tin” Mission with his arm daringly close to a decorous young lady in a large hat. There are pictures of the ships moored along the Dyke, where the coal was loaded; and the beach where the apprentices hung out; and the country estate at Toronto, Lake Macquarie, outside Newcastle, where the hospitable Castleden family went to live.

In a postcard to his grandfather from Newcastle the year after his first visit, when Monkbarns was again in town for two months chasing cargo and crew, Bert wrote “… Last night when we left the mission a large crowd off other ships came down to the wharf to see us off in the launch. As we were leaving they cheered us and the nine of us answered as well as possible. Then we sang “For he’s a jolly good fellow” till we were hoarse. I have never heard any other ship’s crowd of apprentices cheered before, except as last voyage. That shows that the Monkbarns is a very popular ship in Newcastle. Goodbye from Hubert S. Sivell.”

Monkbarns left Newcastle in April 1912, the day after Titanic was lost. The first headlines were just emerging. Loss of life was reported to be great. Bert sent a view of Stockton church ashore with the tug, inscribed only “Just off to Taltal”.

Read on: Too late: Harry Fountain

Previously: Monkbarns and the sail-maker’s palm

Work in progress: the book I never wrote about the sailor grandfather I never knew, from his apprenticeship on the square-rigger Monkbarns to his death by U97, presumed lost with all hands aboard the Shell oil tanker Chama in 1941 Blogroll

Written by Jay Sivell

June 9, 2010 at 12:49 pm

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Historical postcards, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice

Tagged with apprentice, Captain James Donaldson, discipline and desertions, handelsmarine, John Stewart & Co, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, marina mercante, marine marchande, Mission to seamen, Newcastle NSW, Rev Forster Haire, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, Santos, square rigger, Stockton NSW, Taltal, Tin Mission NSW, windjammer