Posts Tagged ‘first tripper’

A sailor’s life – 80. Worse things happen at sea: the steward’s story

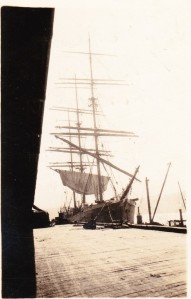

Monkbarns unloading nitrates in Walsh Bay No 10 Sydney, May 1925 (Copyright estate of Eugene Bainbridge)

David Morris called himself a journalist, a writer. He’d been on the lookout for a job on a square rigger for months before he heard of Monkbarns in Sydney in June 1925. He wanted “atmosphere” for some historical sea stories he was preparing to publish, he told the Newcastle Sun as the ship loaded Australian coal for South America. He wanted thrills, he wanted to “see the Pacific at its worst”.

Around him on deck, eyes slid away. “Some of the crew, with that superstition born in seamen, are inclined to regard him us a hoodoo,” the reporter noted.

Three weeks earlier Morris had shot across to Walsh Bay, Sydney, where the ship was discharging nitrate, and buttonholed the mate, offering himself in any capacity at a nominal wage. The mate had said “Nothing doing”, but as he trudged off down the gangway, they’d had a rethink. If he really wanted the experience, said the master, he could come along as a general helper at £2 a month (about £1,000 per annum today.)

Was it a cheap shot they’d expected him to refuse? Morris called himself the Captain’s steward, though he appears on the crew list as Cabin Boy, but pay for a seaman was £10 a month, not £2. Then again, as steward or “boy” he didn’t have to go aloft in all weathers or stand his trick at the wheel. He was a housekeeper, minding stores and dispensing first aid.

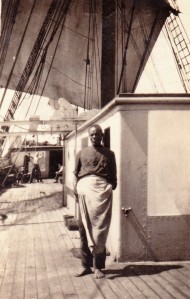

“Yesterday Morris was caught sewing his shirt, with stitches that would disgust a housewife, on the steps leading to the poop deck. He is a well-built man of 25, but he looks more like 30. The small moustache on his upper lip, and the tan shoes and the tweed suit already soiled by work in the galley, looked strangely out of place there,” said page 6 of the Newcastle Sun.

Movie poster for The Ship from Shanghai released in 1930 (http://adventures-of-the-blackgang.tumblr.com/

London-born Morris had visited most ports in the world as a passenger, and had slept in some of Australia’s best hotels and its least inviting parks in his quest for “atmosphere”, readers learned. He had been inspired to join Monkbarns by the runaway success of a sea thriller published the previous year by another young Australian journalist, Dale Collins. Ordeal is based on a round-the-world trip Collins made aboard the motor yacht Speejacks as historian to the US cement magnate Albert Younglove Gowen, who happened to be on his (second) honeymoon. The novel – about seamen turning on their idle rich passengers – was filmed in 1930 as The Ship from Shanghai, with Louis Wolheim as the ship’s crazed steward who holds them all hostage.

Morris was quite frank about what he was up to; there were men on Monkbarns who had had remarkable experiences, he told the newspaper, and he wanted to “chase up” some of those real-life stories. But he seems to have fallen short on listening. This may have been a world of horny-handed hard cases risking life and limb in all weathers aloft, but they still wouldn’t set sail on a Friday, or whistle for fear of challenging the wind, or even say “pig” out loud.

Of the 28 men and boys who had left Liverpool in March 1923, one was dead – a 19-year-old apprentice lost lashing down an escaping sail during a hurricane – two had been left behind in hospital injured, and two more would die before they dropped anchor back in the Thames in 1926.

Monkbarns 1923 securing lifeboats under heavy seas off the cape (probably photographed by 3rd mate Malcolm Bruce Glasier)

By June 1925, only the captain, the mate, “Sails”, a couple of ABs and the older apprentices remained of the original company. It was they who had faced down disaster on the passage out, when a hurricane south-west of Good Hope knocked them so badly that the cargo shifted. With the lee side of the ship 12ft under and green seas raking the deck, it was they who had risked their lives deep in the hold, shovelling rock salt uphill for three days to try to right her. Young Cyril Sebun was lost off the upper topgallant yardarm while they laboured. But nothing could have been done to save him. The boats were all smashed.

Eventually, they put into Cape Town in distress – a first for Captain William Davies. “During my forty years of service in sailing ships I have never had an experience that can in any way compare with this recent one, and to be quite frank, I should not like to pass through a similar ordeal again.”

On arrival in Australia, three seamen deserted – abandoning their pay – and Morris’s predecessor killed himself with an overdose of chloroform. He had been drinking heavily, the inquest noted. He was buried in Stockton NSW, where some of his former shipmates from the SS Argyllshire called the following spring. They sang Welsh hymns at his grave, and laid artificial flowers. They knew.

So, it was not surprising that Morris’ taste for ill winds made his shipmates uncomfortable and by the time Monkbarns had been at sea for two months, things had turned nasty.

Three entries from the diary kept by one of the apprentices, Eugene Bainbridge, offer a snapshot: 23.8.25. Sunday. Played Bridge all day and was 600 up to finish. It has been quite parky lately and it was anything but warm at the wheel from 12-2 tonight. Course ENE, on starboard tack. Shaved David Morris’s beard in half deck after putting him forcibly on the floor. He seemed a bit peevish and didn’t play ‘Vingt et un’ very well afterwards. The job we made of his beard wasn’t very good.

24.8.25. Monday. Clear, calm, sunny, fresh. Doing about 2-3 knots. Course ENE. ‘Maurice’ came in for about two minutes tonight. He seemed to know that there was something in the air and beat it.

The Pelican Society photographed by Eugene Bainbridge – Newcastle-Callao 1925 (Copyright estate of Eugene Bainbridge)

25.8.25. Tuesday. A night of revelry of a peculiar sort. The subject was ‘Maurice Moscovich’. Notices were posted on the half deck doors inviting you to a singsong to be held in the fo’c’sle at 6.30pm. The Mate was particularly asked to refrain from blowing 2 whistles and when told why, was quite sympathetic. At 6.30 sharp, we met and the subject [Morris] had wandered into the gay party.

It was a bluff. He was to be seized in the middle of its proceedings and tried by the chief Pelican and his confederates. All passed off as planned and the victim was found guilty of not supplying the fo’c’sle with molasses and duly sentenced to have his port beard and starboard ‘tache shaved off. Cold water was used to emphasise the gravity of the act, and Bill Hughes, the Court Hairdresser, operated.

But worse was to come, because Morris evidently put up resistance to the assault, verbally if not physically. Bainbridge, a 21-year-old ex-boarding school boy from Maida Vale, London, records that the victim was deemed to have been “unduly insolent” to his tormentors – and a vote for death by dropping over the after part of the poop was passed.

Maurice Moscovitch as Shylock at the Royal Court, London, 1919 (From: http://exhibitions.europeana.eu/exhibits/show/yiddish-theatre-es/jml-las-obras/item/130)

It is possible that there was more than a little anti-Semitism in this “hazing” as Maurice Moscovitch was a well known Russian Jewish stage actor that summer wowing Australian audiences with his Merchant of Venice and Morris’s middle name was inscribed on the crew list as Isidor. Bainbridge had been to see Moscovitch at the Criterion theatre while Monkbarns was in Sydney.

More worrying still, the punishment meted out – for poor stewardship of the few treats that made the ship’s diet of salt meat and pulses bearable – apparently had the backing of the Master and the Mate. Bainbridge writes: We next trussed him up in a sack etc and took him aft for the mate’s inspection.

The procession marched solemnly back singing ‘For it’s a Lie’. Prisoner was next trussed up again (more securely) and taken forth to his execution. Maurice was marched up on to the fo’c’sle head and lowered away over the break. The wash tub was underneath and someone was making a noise like water. The stunt worked so far and when about a foot off the deck, the word was given and Maurice was dropped!!! He arrived in a heap at the side of the ‘donkey’ [steam winch] amid cheers and benedictions from the High Priest.

Had Morris believed his hostile playmates were actually dropping him gagged and bound into the Pacific? It seems more than possible, but he showed his mettle by joining them in the fo’c’sle, where proceedings continued as a “sing song”, and reciting a chunk of Kipling for the company. Whereupon everyone joined in a hearty chorus of “For he’s a jolly good fellow” and peace descended. Bainbridge wrote: The Old Man and Mate were both observed to be enjoying it uncommonly.

Many years later, “Bill the Court Hairdresser” – by then Captain William Hughes, sir – remembered David Morriss [sic] and his quest for atmosphere. “He got it all right, and I’m sure that what he went through before reaching London would fill two or three books,” he told AG Course, chronicling the history of the John Stewart ships for his book The Wheel’s Kick and The Wind’s Song.

View of Valparaiso harbour with Monkbarns marked by apprentice Eugene Bainbridge with an arrow at the bottom (copyright estate of Eugene Bainbridge)

Two months later, just outside Valparaiso, he was still annoying the apprentices (Dave joins us, and we are bored to a standstill with his platitudes!) but he’d graduated from ‘Maurice’ to Dave. And in port, Dave showed a pleasing openhandedness with the ship’s stores as the apprentices rowed around visiting and being visited by boys from neighbouring ships. (Dave got us some stores and there was plenty of scoff. He unfortunately spoilt this good turn by telling some of his tall yarns.)

However, as soon they put out to sea again and rationing restarted, the moans resume. 9.3.26. Dave wants to substitute sugar for molasses instead of substituting jam. This is not a fair exchange as sugar doesn’t go well with bread and butter! 5.5.26. Dave has been making mistakes with the weighing out of the butter and the tins containing so painfully small a quantity we complained and found we were getting less than our whack!

Happily, nine months after Morris’s sentencing by the Pelican Club, the horseplay had become rather more inclusive, if no less rough. By then, Captain William Davies was dead in Rio de Janeiro, the Mate was the new Old Man and the ceremony as Monkbarns passed Lat 0° 00’ 00” was a more or less welcome letting off steam after a very trying few months fighting their way round the Horn with the dying man refusing to put into port.

Young Bainbridge had a ringside seat. 9.5.26. Sunday. Crossed the Line last night. We all ‘felt the bump and noticed that the ship was going faster downhill!!’ At 1.30, I was let into the secret by Bill that we ‘offenders’ had to ‘go through it’. The Old Man had made some pills of ginger, glycerine and several other ingredients and covered them with sugar (of which there is a very large quantity aboard from Rio.) Jim had made some very ‘choice’ mixture of tar, tallow, soap, Melado (molasses) and red lead.

Monkbarns, Neptune’s court May 1926 – crossing the Line. Neptune and wife right, Dave Morris and Eugene Bainbridge among the tarred six on the left (copyright estate of Eugene Bainbridge)

In time honoured tradition, Neptune appeared over the side clad in oakum and bearing a huge trident made from the mast of the for’rard boat, accompanied by his Wife, his Barber, his Parson – in a lead foil cassock and paper collar – and his Doctor carrying the bag of pills. They set up court on the main hatch.

Bainbridge and Morris were among six “first trippers” the god of the sea wanted to inspect for fitness.

I was first blindfolded and then marched to the main hatch, falling over several ‘lines’ drawn across the deck. We had made the washhouse door fast and they had to break the handle off to get in. I was first asked by Neptune why I had done this and if I had crossed the Line before and why I hadn’t been ‘put through it’!

I then kissed his wife’s foot, which was covered with tar and was then shaved using the mixture, getting plenty of it in the mouth. I received the pills and spat them out. At a second shot, I managed to conceal one behind my tongue but before I could remove it my mouth was sore! I finished up being tipped backwards into a tub of water and then liberated. After I had seen two or three others done I went onto the boom and caught a 24lb bonito, which we had for tea. The proceedings broke up with all hands ‘splicing the main brace’.

They were back in the northern hemisphere after three years away, and “home” suddenly seemed closer. But Monkbarns’ adventures were not over. Progress was slow. Supplies ran out. By 450 miles off the Lizard they were down to rice and ersatz bread, but once into the shipping lanes an obliging German steamer provided relief.

They brought the boat alongside and the provisions pulled aboard: three sides of bacon, two hams, two cases of spuds, three sacks of flour and about 16 tins of Argentine boiled beef (we had some for tea and it was excellent), a certain amount of margarine and butter for the cabin, also lard and Dutch evaporated milk. Then the Cook gave us curry and rice for breakfast!!!!!!!! It was nearly the last of him.

But two weeks later they were still 12 miles off Portland Bill, and “reduced to rice, tea and a little jam and bread”, according to another unpublished diary of that voyage, by able seaman Dudley Turner. “Not had a smoke for weeks, which makes matters a lot worse.” And the Old Man was refusing to flag down any more ships.

When they picked up the pilot off Dungeness and it was discovered he handed out cigarettes for good steering – the first tobacco seen aboard for weeks – there was a rush to relieve the wheel frequently. “Never had such good steering been seen before by the old ship,” wrote Course. But they were so undernourished that the tug crew had to help them haul the hawser aboard.

At 6pm on 10 July 1926, Monkbarns dropped anchor off Tilbury. The pilot presented them with a sack of potatoes and Bainbridge records a “memorable feed of sausages and boiled spuds!!! Never was a meal so appreciated”.

The following day they were towed up to Charlton Buoys, a vessel from a bygone age gathering crowds on the banks, and there the crew were paid off.

And there the story ends. Monkbarns was sold “foreign”, and towed to Corcubion in northern Spain to end her days as a coal hulk. Eugene Bainbridge abandoned the apprenticeship for which his father had shelled out £42 and never went to sea again. What became of David Morris I cannot tell. Bill Hughes thought he’d gone in to radio in Melbourne. If he ever wrote up his historical sea stories, neither AG Course nor I could find a trace.

Bizarrely, the real thrill-seeker aboard Monkbarns that trip turned out to be the youngest apprentice, 17-year-old Len Marsland of Brisbane. After rounding the Horn in sail, in 1929 he pops up as a member of Sir Douglas Mawson’s Australian Antarctic expedition. He worked as a prison guard in Canada, chased the explorer Sir Hubert Wilkins across the Atlantic in an attempt to sign up for his submarine expedition under the polar ice, reappeared in Reykjavik, erecting a signal station, and then back at sea as an officer on an icebound freighter in the Baltic and facing down machineguns in a Russian Black Sea port. Tragically, Marsland’s adventurous career was short. While working as a stuntman for Sir Alan Cobham’s famous flying circus in 1935 his parachute failed to open. He fell 1,000 feet and died in Esher, Surrey, aged just 27.

Previously: A doctor aboard 1913

Written by Jay Sivell

May 29, 2016 at 12:39 pm

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Other stories, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, Uncategorized

Tagged with AG Course, apprentice, cabin boy, Captain Bill Hughes, Captain William Davies, Cyril Sebun, Dale Collins, David Isidor Morris, discipline and desertions, Eugene Bainbridge, first tripper, Frederick Leonard Marsland, handelsmarine, John Roberts, John Stewart & Co, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, marina mercante, marine marchande, Maurice Moscovitch, merchant navy, Newcastle NSW, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, seamen's pay & conditions, ship's steward, square rigger, SS Argyllshire, Tall ships, The Ship from Shanghai, Valparaiso, Walsh Bay Sydney, windjammer

A sailor’s life – 75. Sniffing Stockholm tar

In my sailor grandfather’s footsteps I have blagged my way into an oil refinery and onto a Shell tanker, I’ve crossed the Atlantic by container freighter and dropped a wreath into the night black sea at 49° 35’N, 19° 13’W where he and his final crew were lost – I have even traced and befriended the last old man of the U-boot crew that killed him.

For nearly 20 years I have read letters and diaries, rooted through archives, pored over photographs and asked damn fool questions of elderly seafarers who have shared their yarns with gentle amusement. But I remained an armchair sailor, sitting in the warmth, reading about a life beyond my understanding.

It was on a wet day in Liverpool docks that I ran into the Stavros S Niarchos, a dinky, modern sail training brig – square rigged on two masts, a charity venture providing outdoor challenges to young people.

And also, it transpired, to the not so young. Anyone up to 80 could have a go, said a grey-haired woman on the quayside. Was I too old to climb out along the yards, I asked – to try to experience what 16-year-old Bertie Sivell had seen and felt when he first went aloft a hundred years ago? Certainly not, she said, she had.

The author – climbing past the fore t’gallant (right) to the royal beyond, where photographer is perched (see boot).

Anyone who ever read Treasure Island under the bedclothes and fell asleep dreaming of clambering among the spars of a tall ship will understand (and we who read by torchlight in the old days before duvets and Kindles know who we are). To swing up the swaying ratlines and out along the foot-ropes, and see “my” ship splice the waves 120ft below; to roll along a pitching deck, at one with the swell, dodging sheets of spray; and to lie down each night tired but buzzing and be rocked to deepest sleep?

I signed on.

Stavros is not Monkbarns. For a start she is smaller, with two masts not three and fewer yards and sails. She also has two engines, GPS, refrigeration – and heat and light and hot showers and plenty of fresh water and good food. In fact, my grandfather would scoff that my so-called experience in sail bears more resemblance to glamping than the conditions he endured when he began his career at sea as an apprentice in Monkbarns in 1911.

What a difference 100 years makes. The barrels of pork and beef gristle in brine are gone. The yawning cargo hatches and mountains of coal or guano, or slimy stone ballast, that had to be winched in or out basket by basket are gone. Nowadays safety lines snake up the ratlines and along the yards, where there was once only a boy’s own grip. The old cry of “One hand for the ship and one for yourself,” is not quite so scary when you’re wearing a stout harness and clip-on carabiners. Monkbarns suffered countless injuries, as well as losing two young lives overboard in just three years in the early 1920s – Laurence O’Keeffe off the jib-boom and apprentice Cyril Sibun in a fall from the fore upper t’gallant. They were 18 and 19.

On Stavros clean, dry pipe cots with reading lights and lockers fill the t’ween decks where Monkbarns’ apprentices would have shovelled and sweated to trim (balance) the cargo, and out along her bowsprit net “sailor strainers” prevent accidents. But working a sailing ship is still not for the faint hearted.

I have shuffled out along the yards, muscles cracking as I wrestled to haul up and lash down the heavy clew of the sail high out over the waves. I have swung one-armed under the great steel yards, groping for gaskets blowing in the wind, and tied knots one-handed up and down the jackstays.

I have tailed on and hauled “with a will” among ill-assorted strangers until my shoulders strained in their sockets and the hairy hemp lines blistered my office softy palms, and rolled into my bunk sound asleep at 8pm to rise again fully clothed at midnight, to relieve the watch on the open bridge, donning gloves, scarf and waterproofs against the cold summer night. In a week the motley novice “crew” – paying travellers of all shapes and sizes – find themselves fused into a team. A ship’s crew. (Although our professional merchant navy officers probably think fondly of the days when a sailing ship cargo lay inert in the hold for the duration and didn’t need wetnursing.)

Together we have seen sails silhouetted against the stars – more stars than most of us city dwellers ever imagined, and the milky way arching overhead from horizon to horizon. We have sailed into the sunset and watched for dawn, eyes peeled for the pin prick lights of the fishing fleet. We have learned the ropes, and the buoys and the markers.

So far I have not been out of sight of land for more than a week, much less braved day after relentless day of gale-force winds, or icebergs round the Horn, but I have felt the pitch and roll of a tall ship doing 10 knots under sail and watched the horizon tilt and tip under the solid curl of the mainsail. I know the sound of the seas crashing past the scuppers and have tasted salt in the spray.

I may be just paddling in the shallows of my sailor grandfather’s life, but I have sniffed Stockholm tar.

Suddenly, the dusty records have colour and movement. This winter I shall abandon the archives again and join the paint gang aboard Stavros in Liverpool docks, chipping and cleaning, learning “my” ship from the rivets up, and next spring with a crisp CRB certificate in my pocket I hope to sail as volunteer crew – as cook’s assistant, if that’s what the ship needs.

Somewhere, my grandfather is laughing.

Previously – Monkbarns: Britain’s last Cape Horner?

Next – The medals in the post

Read from the start:

A sailor’s life – beginning, middle and end

Written by Jay Sivell

October 14, 2014 at 9:46 am

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Modern square-riggers, Other stories, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, Uncategorized

Tagged with aloft, Bert Sivell, brig, crewing, Cyril Sibun, first tripper, handelsmarine, Isle of Wight & Sivell family, koopvaardij, last days of sail, Laurence O'Keeffe, learning the ropes, leisure sailing, life at sea, marina mercante, marine marchande, merchant navy, rigging, sail training ship, sail training vessel, square rigger, Stavros S Niarchos, Stockholm tar, t'gallants, Tall ships, Tall Ships Youth Trust, Tenacious, voiliers, windjammer, zeilschepen

A sailor’s life – 74. Monkbarns: Britain’s last Cape Horner?

She was obsolete the day she slipped into the Clyde in June 1895: a steel-hulled, full-rigged, three-masted windjammer launched into an age of engines barely two years before Rudolf Diesel changed the world of shipping forever.

The flax mill owner who had commissioned her, Charles Webster Corsar of Arbroath, named her Monkbarns after a local character from a Walter Scott novel (The Antiquary) and demanded everything of the best. The decking and rails were of teak, the accommodation for officers and crew particularly fine. “Her outfit includes all the modern appliances for the efficient working of such a vessel,” reported the Lennox Herald, the Saturday after she was floated.

As a final touch, Corsar even gave her a little white Pegasus figurehead – which would make Monkbarns and her “Flying Horse line” sisters, Fairport and Musselcrag (1896), recognisable around the world. It was not whimsy but canny branding: Corsar’s flax mills and manufactory in Arbroath supplied the sailing ship canvas sold by the family’s cadet branch, D. Corsar of Liverpool – every bolt of it stamped with their trade name, Reliance, and a little flying horse.

The Lennox Herald did not mention the figurehead, nor any further detail, merely remarking that the naming ceremony was carried out by Mrs David Corsar, Jnr, of Cairniehill, Arbroath.

The launch of Charles Corsar’s full-rigged ship Monkbarns, reported in the Lennox Herald, West Dunbartonshire, Scotland, in June 1895

In fact, the launch by Messrs Archibald McMillan & Son (Limited) merited only a single paragraph in a round-up of Dumbarton news that week, wedged between reports about two men being fined 20 shillings each for driving without lights and a rumour in the Glasgow Herald that the Union Steamship Company of New Zealand was buying five new steamers, possibly from Dennys of Dumbarton, which had “built the greater number of vessels for the line, and will probably run a good chance of getting at least some of the work”.

The reporter’s description of Monkbarns having “all modern appliances”, however, echoed down the years. Frank C. Bowen wrote in 1930 that she had “every modern labour-saving device for working the cargo and sails” (Sailing Ships of the London River), and most subsequent authors took him at his word. Yet Monkbarns’ apprentice boys might have considered the matter rather differently.

Like every other sailing ship of her age, she had neither light nor heat. The White Star liner Majestic, completed five years before Monkbarns, catered for 4,100 passengers with an à la carte restaurant and Pompeian swimming pool. But Monkbarns had kerosene lamps and the galley fire (weather and cook permitting). There was no electricity for refrigeration. Fresh vegetables and fruit barely lasted out of sight of land. Potatoes were stored in the dark and given a haircut every week or so. Meat was “preserved” in casks of brine. Margarine came in tins. Coffee was drunk black. Even the water was rationed.

The boys were trainee officers – set apart from the sailors in the fo’c’sle and their masters in the saloon aft by virtue of being unpaid. They lived in the “half-deck”, an iron bunkhouse amidships, which on Monkbarns latterly consisted of two rooms and a corridor with doors either end so that entry could always be from the lee side of the ship while at sea. It was an ice box in the winter and an oven in the tropics, but it had a skylight exit and a “monkey bridge” to the poop that was popular in heavy seas, when the decks were often awash to a depth of two feet or more.

Monkbarns’ half-deck had bunks around the walls on three sides; a bare deal table with raised sides in the middle – flanked by boot-marked benches; a pot-bellied iron stove fed with coal filched from the cargo; and a battered cupboard in the corner divided into lockers, with fancy knotted rope tails for handles. There was a mirror, mottled with damp, and a single smelly kerosene lamp swinging in gimbals.

The bunks were narrow, with high boards along the open side to stop the sleeper rolling out as the ship pitched, and coloured pictures – often of girls, sometimes a country scene – pasted to the surrounding bulkhead by previous occupants. By some hung a canvas “tidy”, containing needles and cotton for repairs. The apprentices had to do all their own own mending, darning and cobbling. Laundry had to be done in salt water, in precious time off and only when there was chance of the garment drying.

New boys would arrive each trip with shop-smart dungarees and new straw mattresses, which the old hands in patched gear would regard balefully. Their own bunks were bare except for blankets, and within weeks the new boys learned why, when the “donkey’s breakfasts” had to be tossed overboard crawling with bed-bugs. Wet oilskins stayed wet, and chafing salt water boils were endemic.

Aboard Monkbarns “all modern appliances” did not include a donkey engine until the mid-1920s, and in many ports her cargo was loaded and discharged by hand – the boys shovelling Australian coal out through the hatches basket by basket to waiting lighters off the coast of Chile, until the dust grated in their lungs and ground itself under their skin. As the last basket was hoisted out there would be shanties and a well-earned tot of whisky – unless the Master was a teetotaller.

Then work would begin again, scouring out the filthy holds for the arrival of saltpetre, 200lbs a sack, which had to be swung aboard and stacked one by one in pyramids below. Monkbarns took about 3,000 tons, or 34,000 bags. The air would be like soup. Out in the Chilean anchorages, in holds lifting and falling in the long Pacific swell, the evaporation from the bags was known to kill rats and even woodlice, and ship’s cats would lie down in dark corners and not wake up.

Guano was considered worse, a throat-catching green powder of ancient bird droppings scraped off rocky outcrops further north, off Peru. But nowadays potassium nitrate is considered too dangerous to handle, let alone breathe.

Priwall – four-masted barque built by F. Laeisz of Hamburg for the nitrate trade – had steam winches and shore staff

The beautiful four and five- masted barques that set records and made fortunes for A.D. Bordes of Bordeaux and F. Laeisz of Hamburg shifted up to 5,500 tons of nitrates in eleven days flat, but they had steam winches – four to a hatch – and a small army of cadet officers and shore staff. Monkbarns did not.

Monkbarns boy Eugene Bainbridge, rowing around the bay visiting the other ships in Iquique in 1924, wrote enviously: “Priwall, which we went on next, was the antithesis of the Rhone, being spotlessly clean. She had every modern fitting – brace-winches (motor), halliard apparatus for two men to raise the halliards with ease, and a derrick on the jigger. Two wheels amidships with cable connection aft, where there are two more wheels under the poop. The Third Mate showed us the Captain’s saloon, decked up with light polished wood round the walls and carpet on the floor. She also carried plenty of spare spars etc. […] There was a bunk in the chart house for the Old Man, and a crowd of English charts used on the voyage round the Horn. We had a look at the log book, which registered one week nothing but 12 and 14 knots!”

Notwithstanding the rise of the oil industry by the 1920s, Corsar was not alone clinging to canvas in 1895. Many of the names familiar to us from the last days of sail were built after Monkbarns, including Penang and Pamir (both 1905), Peking and Passat (both 1911).

Laeisz had in fact only completed Priwall four years previously, in 1920, having been interrupted by the First World War. (In 1939 she arrived Valparaiso just in time to be trapped by the Second World War. She was interned, and 1941 was donated to the Chileans to avoid her falling into allied hands. Renamed Lautaro, she continued in the trade until she caught fire and burned out in 1945 while loading a cargo of nitrate off Peru.)

View of Valparaiso bay from Naval School. Ships left to right: Peru, Santiago, Monkbarns, Taltal, Queen of Scots (white hull) and Valparaiso in dock. Extreme left: barque California. E. Bainbridge collection

Though most sailing ships were less well equipped than the ships of the Flying P-line, they were still holding their own against steamers on the longer routes, to Chile and Australia, because of the price of coal – and the demand for sail-trained officers that would continue in motor-ships and oil tankers for many years to come.

Boys were cheap, British ships indentured them for four years largely unpaid and by 1919 (following a mutiny aboard) Monkbarns had expanded her deck housing to accommodate a dozen of them. They often made up half the crew. Steamers couldn’t afford to hang around, but sailers could. And hang around they did, for months at a time by the end, waiting for a charter.

Monkbarns left Valparaiso with her last cargo under sail in early 1926: a load of guano salvaged from another victim of Cape Horn, Queen of Scots. After they had sailed, the boys spent several days trimming the ship, wheeling the filthy stuff down the deck from the fore hold to the hatch aft. The ABs had refused, but the boys couldn’t.

As is recorded elsewhere, it was to be a weary voyage; Captain William Davies died – probably of stomach cancer – and they put into Rio, they were becalmed, suffered baffling winds and ran out of food.

They finally arrived in the Thames under tow after 170 days out and anchored off Gravesend, amazed at the sheer volume of traffic, big and small steamers passing in a continuous stream. Fresh meat and veg were delivered aboard and dinner that night was sausages and boiled potatoes.

“I can say that never was a meal so appreciated,” wrote young Bainbridge. The following morning they began heaving up the anchor at about 8.30am, to the shanty Rolling Home followed by Leave Her, Johnny, Leave Her, for the final leg to Charlton Buoys.

“All hands joined in with a will, even the pilot, so that the echo went ringing over the river and a large crowd gathered on the shore to listen,” wrote able seaman Dudley Turner in the fo’c’sle. “The pilot even grabbed a capstan bar and tramped around with us singing In Amsterdam There Lived a Maid.”

It was July 1926, and Monkbarns was the first full-rigged ship to come into the Port of London for eight years, “a wandering and lonely ghost which we may not see again,” wrote The Star. The Times called her “a picture out of the romantic past”.

Chips the ship’s carpenter was more prosaic. “I’ve had six meals since I came ashore 16 hours ago,” he told the Westminster Gazette, “and I’m still hungry.” Monkbarns was to find only one more cargo – Welsh coal, which she delivered under tow, to Norwegian whalers off Corcubion in northern Spain the following March. She finished her life as a coal hulk – the last British full-rigged ship to sail round Cape Horn, according to Alan Villiers (Sea-dogs of To-day, 1932), still bunkering passing steamers into the 1950s.

My last sighting is from a personal letter. Brian Watson, later senior pilot/deputy harbour master at Montrose, was then a nosy British steamship apprentice in the Baron Elibank. In 1954 he spotted a name in raised letters on the nearby bunkering hulk after his ship had sought refuge in Corcubion bay during bad weather. He recognised she was an old Britisher and climbed aboard for a look round.

In 1999 he wrote: “We berthed alongside a coal hulk and I could clearly see her name Monkbarns the metal letters still visible on her counter stern.” He said the masts had been cut down to stumps and he thought the bowsprit had been cut away, most of the deck and poop cabins had been stripped, a rusting galley stove had been moved into the poop accommodation.

Unfortunately, he was spotted by the steamer’s Mate and chased back to work before he could check the bows for the little white horse. The hunt continues for Corsar’s last figurehead with local help. More Watch this space – https://historiasdebarcosyveleros.blogspot.com

© Jay Sivell

This article has been amended since it appeared in The Cape Horner magazine, the journal of the International Association of Cape Horners. August 2014, V2 No 65

Next – Sniffing Stockholm Tar

Previously – In Remembrance: Save our Ships

Written by Jay Sivell

October 8, 2014 at 5:21 pm

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, Uncategorized, WWII

Tagged with apprentice, Cape Horners, first tripper, handelsmarine, John Stewart & Co, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, marina mercante, marine marchande, merchant navy, Monkbarns, Priwall, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, seamen's pay & conditions, square rigger, Tall ships, windjammer

A sailor’s life – 72. Death of a master, 1926. Monkbarns’ last trip

He was the teenage only son of well-to-do parents, with uncalloused hands and a yen for real life. Mother and Father – a marine insurance broker – were off on a world cruise for their health, so they packed him off on one of the last British windjammers.

And that was how Eugene Bainbridge, ex-Marlborough College, joined the motley crowd in the half deck of Monkbarns with his expensive Leica in Newcastle NSW in 1924 and set sail for two years on what would turn out to be the old square-rigger’s very last trip.

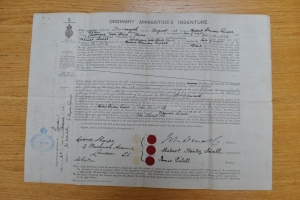

Bainbridge père paid £38 for Eugene’s third class berth out on the P&O passenger ship Barrabool – which was nearly five months’ pay for the men in Monkbarns’ fo’c’sle. John Stewart & Co apprentices, of course, as their indenture papers firmly stated, received “NIL”.

But even with half the hands working unpaid, the sums for the old windbags were no longer adding up. One by one, John Stewart’s fleet had been sold for scrap. Monkbarns was among the last four, and she had been laid up in Bruges for over a year until a lucky cargo of rock salt brought her out of retirement in 1923 one more time.

By Christmas 1925, she was in South America, in Chile, and the “boys” in the half deck saw in New Year 1926 stowing half a cargo of guano picked up from a derelict in Valparaiso bay – another old sailer that would never see Europe again.

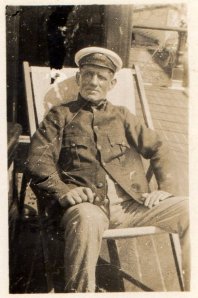

Monkbarns at sea, October 1925 – Captain William Davies, Ian Russell AB at helm and ‘Sails’, Henry Robertson – private collection E. Bainbridge. “The Old Man went below to put on a clean collar”

They left in mid January, bound for home via the rough passage round the Horn. So far the voyage had already claimed two lives since the ship left Liverpool three years earlier – an apprentice lost overboard off one of the yards in a gale and a suicide by morphine overdose in Newcastle NSW – and now the master was dying of stomach cancer, but the seven apprentices didn’t know that.

Two days out of Valparaiso, Eugene wrote in the diary his dad had given him:

“23.1.26 Saturday. Washed half deck with John [Davies]. Took wheel 12-2pm. It struck me again what an advantageous point of view the wheel is. Everything puts on a more pleasing aspect as one views the quarter deck, and shipmates busy with some uninteresting job seem to hold an enviable position. The beautiful silence which reigns as you keep one eye on the weather leech of the top gallant sail. The sea is covered with little ripples today but would otherwise present a flat surface. The breeze is not bad, though considerably less than yesterday and the courses are drawing well. The breeze has dropped again but at 1.30 tonight it suddenly livened up and clouds appeared on the port quarter. Hall [seaman] came on to the lookout and started to talk about the copra trade before the high duties in Sydney. He said that it was on account of one or two fires that high duties were put on, and now there is no trade to speak of, the main bulk going to USA.

“24.1.26 Sunday. Oiled my second pair of oilskins and hung them out to dry. Turned in in the afternoon. Still making westerly and no sign of change.

“25.1.26 Monday. Finished chipping anchor chain and tarred some of it. Very little wind and still going to the westward. A fair wind (NW) is about the last thing that anyone would expect and we shall soon be in Australia like this!

“26.1.26 Tuesday. Wheel 8-10. Nothing to do but watch the sails. Wind gradually dying out and ship starting to roll slightly. Fine day and sun very strong. No clouds about. Wind disappeared and rolling at times. Finished the port anchor chain and lowered it into the locker. Hove starboard chain up on deck ready to scrape. Beautiful evening and Dave [cabin boy] joined me on the lookout from 8-9.30. I told him I wouldn’t be entertaining but he managed to get through a fair amount of talking, as usual, and was evidently satisfied. We discussed Goethe’s Faust, or at least, he did, and then he praised Scarlatti and Chopin.

“27.1.26 Wednesday. Flat calm and very hot (85 degrees in shade). Sleeping on main hatch where the night air is refreshing. Scraped the starboard anchor chain, tarred and stored it. This evening, the mate gave me a bucket to put a new rope handle on. I did it after referring to the book and put the usual “simple Mathew Walker” on. He praised them next day.

“28.1.26 Thursday. Flat calm and water like a sheet of glass. Saw big shark off the side of the ship but it went when we got the hook ready. It did not turn when it came to eat some offal which had been thrown overboard!! Started to trim the cargo in the forehold and taking it in barrow to the after hatch to dump. I had the job of standing by the hatch to tip the barrows. Played Langford [sailor] at chess. Slept out on the main hatch. Heavy dew. There are no apples or peaches in the ship, only prunes!”

For three weeks, as the ship made its way slowly out into the Pacific, the port and starboard watches chipped, tarred and stowed the mooring chains, and trimmed the cargo in the forehold, wheeling the stinking choking stuff barrow by barrow to the after hatch to dump. They reeved off new buntlines, downhauls, clewlines and braces. Chips made new blocks, and Eugene stood his trick at the wheel.

By the first week in February they’d swung SSE with the Easterlies and were heading for the Horn, the sea was becoming heavier and the skies had turned grey.

“6.2.26. The Old Man is bad today, and everything is done to stop the ship from rolling,” Eugene noted. “The mate changed course three times tonight for that reason.” In the half deck, a heavy tin of jam fell out of the apprentices’s locker onto Eugene’s head, inflicting damage.

“8.2.26 Monday. The atmosphere is the dampest that I have ever known and the horizon is blurred with mist. Sea and sky are grey alike and the wind from the northward is fairly strong, bringing with it a heavy swell. It was cold at the wheel at 12 o’clock today… The Old Man was a little better today and enjoyed a joke. The mate is very pale and together with overstrain and overwork has not slept for over 48 hours. No sights have been taken owing to the dullness but the mate took some stars last night. Lookouts are kept night and day and a sharp lookout for ice is to be kept. We are standing by all the time now, ready to attend brace or take in sail. When we were doing about 9-10 knots this afternoon and I was at the wheel a school of large Black Fish was keeping up with us. They jumped a little from the crests of the waves and could be seen black beneath the surface quite close. I should guess 12-14 feet would be their length and they had fairly pointed noses and a big thick dorsal fin.”

The temperature fell, day by day. “10.2.26. Wednesday. The temperature today was 45 degrees but it appeared to be much colder aloft and the steel yards stung when gripped. The old man is much better and cracking jokes.”

As they got closer to the Horn, lookouts were posted day and night. They were racketing along at 12 knots, a hell of a speed to hit an iceberg. “Boiled some pitch for the Mate this evening to do the chartroom deckhead. The chartroom and in fact the whole poop is leaking. The heavy sea having strained the seams aft. The two Johns relieve each other and, with the time-keeper, watch over the old man at night. He is not so well tonight. We should round the Horn tomorrow with a fair breeze.”

The Horn was passed in thick mist, shortened down to topsails only, and with their eyes peeled for icebergs. Jock Scott warned Eugene to go to bed fully clothed, “to be ready if anything should happen, so we did.”

Monkbarns half deck. Eugene (right) and John Davies. Jim Holmes in bunk. Private collection E. Bainbridge

The temperature was 6°C (44° F), mild. There were albatross, mollyhawks, stormy and great petrels, and even a penguin around the ship. (“Sails revealed they are always met with down in the South Pacific and Atlantic, and sometimes hundreds of miles from land! This one was a dark brownish grey with a bright yellow streak across the eye. He was up an down after fish and squeaked not unlike the flapping topmast staysail.”)

Once past the Horn, the weather cleared. The ship “steered like a bird, with three spokes either way”, wrote Eugene ecstatically. There were four pairs of albatross following the ship, and a school of Cape Horn white-bellied and white tailed porpoises. Their breathing under the bows made Eugene realise he was not alone on his lookout. He saw and heard several whales. ” The Old Man is much better and has taken to growling at his nurses again in the old style. He has told the mate not to call anywhere or even stop a ship, if sighted. He is certainly an optimist. The position is about 54S 56W”

By the end of the month, it was 70° in the shade and the wind had dropped to 2 knots. The Old Man was being nursed day and night, injected rectally with milk and brandy because he could no longer keep any food down. One apprentice from each watch was set to watch over him. Eugene complained that his friend Jean Seron had been banned from studying navigation in the master’s quarters – a light novel was less distracting. “What hard luck as he never gets a chance to study now, wasting every watch in the Old Man’s room doing nothing. He wants to go for his ticket at the end of the voyage…”

Eugene was not posted to the sickroom. Instead, he was kept busy painting, or bending on sails. Off watch, he sketched, fished for sharks and worked on his model of the ship. The food was now also running low. “Traditional, for a sailing ship,” wrote Eugene. “Grub seems very scarce and uninteresting; beans every day, everywhere substitutes.” They caught and ate a dolphin, boiling the meat for tea. “The cook made a very bad job of it.”

The Mate was at his wits’ end. He’d decided to countermand the master’s orders and head for Rio, or Bahia – whatever port they could reach with the prevailing wind and currents. The Old Man was dying. But by the middle of the month they were still 900 miles from Rio and the ship was becalmed. The weather grew hotter and hotter. The Old Man could no longer bear any noise. Singing was banned, and the accordion. It was 90°F (33C). The Mate rigged a funnel from the skylight to Captain Davies’ bedside, made “of weather cloth and and bucket hoops.”

But the ship still had to be worked. One of the senior apprentices, Raymond Baise, was promoted to acting 3rd Mate. The 2nd, Mr Williams, who had started the voyage as able seaman, took over many of his chief’s tasks and watch after watch they braced the yards, tacking, wearing ship – trying to catch the slightest breath of wind, while the exhausted Mate kept his eye on all, scouring the Ship Master’s Medical Guide for instructions on how to ease the dying man.

They sighted land (Cape Frio) on the 25th of March.

“26.3.26 Friday. Wore ship every watch and made scarcely any ground through doing so. All the courses are of course hauled up to make the handling of the yards easier. Cape Frio was in sight all the time during the day and the light was clearly visible during the night. Several steamers passed the lighthouse and cape during my lookout, and I reported their lights in turn as they came in view. The wind dropped and there was a dead calm before morning. All the ground we made was done in crab-fashion and owing to the Great Brazilian Current, which drifts southward. The wind is a dead muzzler from the west and the ship’s head (steering compass) is S by W on one tack and NW by N on the other.”

On the 28th they sighted the Sugar Loaf, and by evening the Old Man had been taken off to hospital. The 29th, Eugene whizzed through his chores (cleaning brasswork, washing down the decks, getting a sail up out of the locker through the choking ammonia fumes) and tried to go ashore in the launch at 5pm as the Mate arrived back from the hospital. The Mate said “no”, Rio was under martial law.

The following day he tried again, but the Mate didn’t want to share the launch with him. “He saw me coming and had his answer ready, which was that I could not go in the launch with him as it cost money. I asked him how much it would be and he said that he did not know and that anyway he had too many worries to be bothered with people going ashore for pleasure […] He left the ship at 8.30 with the two Johns and I remained on deck gesticulating and whistling to every launch and bum-boat that appeared within hailing distance.”

By 10.20am Eugene was ashore, taking tea and refreshments in the Alvear Cafe on the Rua Rio Branco, before strolling on past the Municipal Theatre, (“very like the Opera House in Paris”) and the Senate. He took a tram part way up the Corcovado, but found there was a two-hour wait for the next train to the top – where the famous Christ the Redeemer statue was still only a pile of bricks. Instead, he marvelled at the lizards, a spider the size of his hand and three people with long nets catching six-inch blue butterflies (“They make beautiful ash-trays”). After that he caught a taxi and went to the Botanical Gardens, where he admired the famous avenue of 100 palms, and then treated himself to an icecream soda before returning to the ship in a bum-boat under its own sail, for 10 Milreis (about 6 shillings, or a day’s pay for a sailor). “And arrived back five minutes before the Mate. There was a loud shout from all hands as I hove in sight.”

Captain William Davies died in the night, aged 61. The telegram to his wife with the first indication that he was ill followed the next day by a second, with the shocking news of his death.

All the apprentices and “Sails”, Henry Robertson, were invited to the brief funeral in Rio’s English cemetery, but there is no description of it in Eugene’s diaries. Only six of them were needed to collect the body from the hospital. Eugene, left to kick his heels in the agent’s office for an hour with Bill and old Sails, recognised a passing Old Marlburian by his school tie, and struck up a chat.

Monkbarns left Rio the following morning in dripping rain and thick cloud under a new Captain Davies, the former 1st Mate, waved off by the agent’s clerk, Eugene’s old school crony Sharpes, who came aboard for a fine display of shantying up the anchor. “An appreciative audience makes a world of difference and I have never heard shanties sung so well aboard the ship,” wrote Eugene. “Bill and Mac supplied most of the solos and the choruses were all hearty.”

The new master was determined to keep spirits up. They were bound for home – across the Line.

…

For the further adventures of Eugene Bainbridge esq.– supported by the newly discovered letters of Raymond Baise (!!) – find me a publisher.

Next – In Remembrance: Save our Ships

Previously – A small man, tubby

Written by Jay Sivell

October 8, 2012 at 11:45 am

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Other stories, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice

Tagged with apprentice, Barrabool, Bert Sivell, Cape Horn, Captain Richard Davies, Captain William Davies, death at sea, eating dolphin, Eugene Bainbridge, first tripper, guano, handelsmarine, historic ship photographs, icebergs, Jean Baptiste Seron, John Stewart & Co, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, marina mercante, marine marchande, Marlborough College, merchant navy, old school tie, Raymond Baise, Rio de Janeiro 1926, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, seamen's pay & conditions, square rigger, Tall ships, Valparaiso, Whales, windjammer

A sailor’s life – 48. Oil tanker apprentice, 1919

Most of Britain’s sailing ships had been sunk or sold by the time Bill Jefferies was old enough to go to sea in 1919. So he signed on with the British Tanker company and became devoted to oil tankers instead. (“Remarkable ships, in many ways” he murmured, half to himself, as he committed his memories to a tape recorder at the end of his life.)

He remembered the “lovely women” who had brazenly boarded his ship during the month he as a “first tripper” had spent in Trinidad in 1919 waiting for cargo. The crew had dropped lines over the side to haul the girls up, and sold the shirts off their backs when their money ran out. By the time the ship got to Port Arthur, Texas, where the Americans inspected every man jack of them, there were less than a dozen men aboard who had not got VD, he recalled.

The captain had forcibly seen to it that the three apprentices kept their noses, and everything else, clean. “He put his big fist under each of our chins and shoved our heads back. And he said, ‘If I catch any of you boys going with any of these women, I’ll smash your faces in so your mothers never recognise you…” Then he took them to the hospital and made them look under the dressings at the ulcerated, seeping genitals of a seaman he knew who was dying there. Bill said: “I told my mother seven months later, when I got home, and she said Thank God for that captain.”

Bill’s mother was a doughty woman who had signed her younger son’s indentures and paid the bond as soon as shipping firms began to recruit apprentices again after the war. Bill’s brother Alf had been an apprentice on John Stewart’s barque Lorton with Algie Course and was one of the crowd of boys in Newcastle NSW with Bert Sivell in September 1913, revelling in the tennis, tea dances and charabanc trips organised by the mission while their ships lay along the Dyke. Bill recalled the excitement he had felt as a ten-year-old being rowed out to his brother’s ship at Tilbury when a wave splashed over him, and the burly seamen nodded sagely and said “that means you’ll go to sea too, lad”.

Apprentices from the sailing ship Lorton, Sydney 1911 - including AG Course, second right, front. From The Wheel's Kick and The Wind's Song, by AG Course

When Lorton was “sold foreign” in 1914, Alf transferred to the barque Edinburgh. But in 1916 she was captured by the raider Möwe. The Germans had hauled out the crew and two live pigs and sent the old barque to the bottom of the sea with all sails set. The tropical night had been so clear, Alf Jefferies used to claim, that they could see her canvas shimmering whitely under the water after she’d vanished. Even the enemy commander was supposed to have sighed “Beautiful even in death”. Among the prisoners below decks, the squeals of the pigs being hoisted aboard the raider were reported to have given rise to the rumour that the Edinburgh’s captain had his wife with him, and that she was hysterical.

By the time Bill Jefferies went to sea, it was a much lonelier life than Alf had sketched. The old square-riggers’ crowd of apprentices had dwindled to just three on Bill’s oil tanker, and even before these greenhorns reached their ship a plausible bloke posing as the shipping agent managed to relieve them of their luggage so they had to be kitted out from the slop chest. Once underway they got seasick and the mate, an old sailing ship man, sent them down the hold to scrape paint pots while the tanker heaved and plunged in a south-westerly gale. After they’d been sick, to windward — another mistake they did not make twice, he ordered them to shift stores. For two days they were kept constantly on the move. But it worked. Bill never suffered sea sickness again.

“They really were a motley crowd, seamen of all nations except our enemies,” said Bill aged 90, remembering that first ship in 1919. “We had a British bosun, a Belgian carpenter – a tall man with fierce whiskers who used to cause a lot of trouble when he was drunk. We had Latvians and Estonians, two Chinese cooks, and a Dutch chief steward. The average seaman in those days was either very old or a foreigner.” The fierce Welsh captain who kept his apprentices out of trouble had been torpedoed five times, or so he claimed.

But by 1920, US production of gasoline (petrol) alone was 116 million barrels (42 US gallons per barrel) – from less than 7 million barrels in 1901. Across the world the oil industry was booming.

Coming next: Clan line or Shell?

Previously: In Remembrance

Written by Jay Sivell

November 16, 2010 at 10:26 am

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, 3. Shell years - 1919-1939, Historical postcards, Other stories

Tagged with apprentice, British Tanker Co, Edinburgh, first tripper, handelsmarine, John Stewart & Co, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, Lorton, marina mercante, marine marchande, merchant navy, Mowe, oil tankers, Port Arthur, Texas, Trinidad, venereal disease

A sailor’s life – 21. Monkbarns apprentice: Harry Fountain

There was a new crop of apprentice boys in the tin bunkhouse amidships by the time Monkbarns arrived back in Newcastle NSW, Australia, in November 1920, after the end of first world war; new faces in the patchy mirror on the bulkhead and new views of “home” pasted to the walls of each narrow bunk. Many of the old sailing ships had been lost, but not “lucky” Monkbarns.

There were four other British square riggers in port too, they remembered, with 37 apprentices between them, plus boys from the French Champagne and Danish Viking. The Monkbarns apprentices were given the afternoon off to hear a concert at the Seamen’s Mission in Stockton and for most of the next month had time off to lounge about the beach, play tennis and go on picnics with the pretty girls, while they waited for repairs to one of the masts.

“We made our own amusement,” wrote Harry Fountain, in The Cape Horner magazine. “There was probably a theatre, there must certainly have been picture houses, but they were ever beyond us with our few pence. I seem to remember that was soon spent in the Niagara Café on banana splits at 9d a plate.”

Captain Harry Fountain, one of many dozens of boys who passed through Monkbarns’ half deck over the years, served the sea all his life and lived to the ripe old age of 95. What became of “Tich” Copner, Reg Bannister (“who snored like hell”) and the Belgian, Marcel Emil Brough, I never discovered, but Fountain never lost touch with his old shipmate Lionel Walker, who had settled on the other side of the world with the Aussie mission girl he had gone back to find.

Jessie Walker’s family gave me his last known address when I traced them – a damn fool Pom grandchild still doggedly hunting witness accounts of life on Monkbarns three-quarters of a century later – and with typical generosity they heaped on me newspaper cuttings and photographs of the charabanc trips and tennis parties. But my letter to Harry in Boston, Lincolnshire, was returned by his executors: Captain Fountain, retired harbour pilot and sometime pub landlord, was finally at rest under the handsome headstone he had bought and gleefully visited for many years on his daily walk to the docks. He told his local paper the secret of his longevity had been cold showers, bread and dripping, and 20 Senior Service cigarettes a day.

The solicitor put me in touch with one of the old man’s friends. “He would have loved to have talked to you,” they both said. I had missed him by four months.

Read on: The nitrate coast, Chile, 1912

Previously: Pommie boys and Aussie girls, Newcastle NSW 1912

Written by Jay Sivell

June 13, 2010 at 4:23 pm

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Other stories, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice

Tagged with apprentice, first tripper, handelsmarine, Harry Fountain, John Stewart & Co, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, Lionel Walker, marina mercante, marine marchande, merchant navy, Newcastle NSW, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, square rigger, windjammer

A sailor’s life – 17. The devil provides the cook

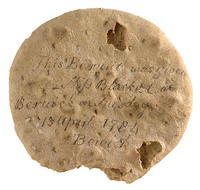

Ship's biscuit, presented to a Miss Blacket in 1784, from the collection of National Maritime Museum Greenwich

Imagine if you will a world without cheese, or milk, or apples, or even a carrot or cabbage leaf. Imagine day after day, tin pannikins with the same boiled salt meat and dried pulses, uniform brown, with never a hint of tomato, unrelieved by soft bread or clean water.

The sailing ship indenture Bert Sivell signed in August 1911 specified that John Stewart & Co were to provide “sufficient” meat, drink and lodging. But “sufficient” is a subjective term.

The provision of food in British merchant ships was regulated by the Board of Trade and a scale was printed in the ship’s articles where all aboard might read it, forestalling argument. But there was a saying in sailing ships that while God provides the food, the Devil provides the cook.

Vegetables and fruit lasted about a fortnight after leaving port, fresh milk and butter rather less. Thereafter – possibly for months on end until the next landfall – there were sacks of rice and flour and split peas, and casks of meat, and evaporated milk and butter in tins.

The Board of Trade stipulated masters should provide each man with a quart of water and a pound of salted pork or beef a day, which was usually served on alternate days with pea soup or rice or (weather permitting) bread, and whatever was left over appeared again for dinner. All quantities were strictly laid down: a pound of bread daily, 1/4 lb rice twice a week, 2 oz of preserved potatoes three times a week, and 2/3 pint of peas. The agreement even detailed acceptable substitutes — a pound of ship’s biscuit in the absence of flour, 1/4 oz of tea instead of 1/2 oz coffee beans.

Tea, coffee beans, sugar, marmalade, butter and condiments were distributed as weekly stores for individual use and safekeeping, and again in the quantities strictly laid down by the Board of Trade.

Although bigger ships might carry chickens and a couple of pigs, they too were prey to the weather, and after ten days on salt meat British masters were legally obliged to serve lime juice, to prevent scurvy, which made your gums swell and your teeth fall out. “Limeys,” jeered American crews. By his mid-twenties Bert needed false plates top and bottom.

Meat on Monkbarns was kept, unrefrigerated of course, in casks of brine below decks and tipped into a locked, iron-bound teak harness cask on deck abaft the mizzen mast as needed. There, it warped in the wet and heated in the sun until the surface ran with all the colours of the rainbow and “care was needed in passing to leeward if you were fastidious”. It was served, boiled with dried potatoes and beans, as wet hash (stew) or dry hash (cottage pie), or sometimes as curry with rice or “Boston baked beans” (in molasses).

On Sundays, as a treat, there was tinned meat and “duff” – plain suet with molasses. And on cold days there was “burgoo” or oatmeal porridge, galley fires permitting. But everything was prone to decay.

Drinking water went brackish in the sun and weevils soon wriggled in the flour, the oatmeal, and even in the hard tack or ship’s biscuits, which were three-inch squares triple-baked to a rock-like dessication that was supposed to ensure they “kept” for five years. The trick was to tap them on the table so the beetles fell out and then soak them in coffee, Bert told his son. He had little sympathy with children who would not eat their sprouts.

In the half deck the growing apprentice boys, always hungry, obsessed about food. Cracker hash and dandy funk were favourites, both featuring biscuit (less “the more obvious weevils”) crushed with a belaying pin, and then either mixed with chopped pork and lard, or with brown sugar, marmalade and a dab of butter. Baked on tin plates by stealth in the galley when the cook’s back was turned the result was, one elderly seadog wrote mistily, “a magnificent delicacy particularly suitable for afternoon tea on Sundays, provided, of course, you are on board a square-rigger bound for Cape Horn.”

As the weeks stretched into months at sea, the packages of little comforts packed by the mothers far away slowly emptied and the new dungarees began to sprout rents and patches. Saltwater boils erupted on necks and wrists from the chafing oilskins, and the daily scrubbing wore calluses into hands and knees.

From the bridge of his Shell oil tanker, not so many years later, Bert acknowledged the past discomforts. “One night,” he wrote, “I think it was last Tuesday, some very heavy squalls came along when I was on watch, accompanied by torrential rain. While they were on I just looked up aloft and smiled to myself that there were no sails up there to be looked after. I kept that watch on the bridge without oilskins or sea-boots and at midnight when I was relieved I was as dry as a bone … and people wonder why they can’t get officers for sail.”

Read on: Corsars’ flying horse figureheadPreviously: Learning the ropes

*Victor Fall and Harry Fountain, ex-Monkbarns apprentices

Written by Jay Sivell

June 6, 2010 at 9:34 am

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Sailing ship - Monkbarns

Tagged with apprentice, cracker hash, dandy funk, first tripper, handelsmarine, hardtack, John Stewart & Co, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, marina mercante, marine marchande, merchant navy, pound and a pint, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, ship's biscuit, square rigger, Tall ships, windjammer

A sailor’s life – 16. Monkbarns: learning the ropes

Bert Sivell recorded that he had arrived on board Monkbarns on August 14th1911, but the ship did not sail until the 22nd. In between, the new apprentices were “learning the ropes” – essential for working an unlit sailing ship at night in a storm when the wrong move was life and death. Everyone — even the cook — had to know the ship’s gear by feel, from the layout of the belaying pins where the running rigging was fastened, to the hemp edging identifying the back of the square sails. If a boy did not know the ropes, if he slackened or hauled on the wrong one in the blackness, he risked drowning them all.

Being neither officers nor crew, and unpaid to boot, apprentices were given all the nastiest jobs aboard, from polishing the brasswork to sanding the deck every morning on hands and knees. Bert spent the first week painting and cleaning, loading food and canvas, and working as a stevedore before the hired hands turned to. But off watch, in the boys’ rank dank little glory hole amidships, squatting on their shiny new sea chests, there were yarns and horseplay and friendships were struck up that would last a lifetime.

Out at sea, the chipping and greasing and swabbing and pumping continued unabated, at the beck and call of the Mate, or chief officer. The boys had to strike the bells on the poop that kept the ship’s time and heave the log, which measured speed and drift, and keep the compass binnacle (the stand) polished and the oil in the lamps topped up. They scrubbed the decks with great ‘holystone’ blocks for hours at a stretch until their backs and knees ached, to prevent the timbers becoming slippery, and sluiced them with salt water to prevent shrinkage.

When there were ropes to be hauled on* [As any fule kno, there is in fact only one rope on a ship, and it is attached to the ship’s bell, the rest are halliards, braces, lines and hawsers, see below, Ed.], the boys pulley-hauled behind the crew and coiled the ends away. They helped take in sail and let out sail, and learned rapidly to jump aloft in all weathers and at all hours, feet splayed along the wires slung under each swaying yard, to grease a mast or slacken off the lines that gathered the canvas “bunt”, to prevent the sails chafing.

Within weeks they were clambering like monkeys, high up among the sails beyond the last tarred rope ratline, from where the ship far below looked like a blade cleaving the sea.

Read on: The devil provides the cook

Previously: Why would you?

Halliards haul up yards, braces swing yards, clewlines haul up the clews or corners of sail to the yard, buntlines gather the body or bunt of the sail to the yard, hawsers are for mooring. Some would say the ship’s bell hasn’t a rope either but a lanyard…

Written by Jay Sivell

June 5, 2010 at 9:29 am

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Sailing ship - Monkbarns

Tagged with apprentice, Corsars, first tripper, handelsmarine, John Stewart & Co, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, marina mercante, marine marchande, merchant navy, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, square rigger, windjammer

A sailor’s life – 15. Why would you?

The story in the family was always that Thomas Sivell, master carriage builder of Ryde, on the Isle of Wight, had packed his only child off to sea in sail to put him off sailoring once and for all. But it would appear the family was wrong again.

Life on the windjammers was cold and hard and dangerous, and no doubt a cruel shock after a year as a flunky on passenger ships. While steamers ate up the miles in straight lines across the ocean, sailing ships tacked and tossed at the will of the wind. They could not sail through Mr De Lesseps’ canal at Suez, linking Europe to the Far East, nor through the new canal being built at Panama to open up the Pacific. Instead, they fought their way south round the Horn and the Cape of Good Hope, adding thousands of miles and months of dangers to their journeys. Ships were lost and boys were killed, but as a training it was considered second to none.

Thomas paid £10 for Bert’s apprenticeship because Thomas was investing in gold braid.

Hindsight proves him right, too. Up to the first world war steam ship companies like Cunard and White Star, with the biggest and most modern engines, sought their officers only among those with experience in sail. The demand outlasted the ships. The Thames and Hull pilot services only dropped the requirement in the 1930s, by which time most of Britain’s sailing ships had been sunk or sold “foreign” to the Baltic and South America, and junior British officers were having to ship with foreign vessels to comply.

If Thomas did quietly harbour hopes of ill-winds, as my father believed, he got more than he bargained for. For the first world war broke out before the end of Bert’s four year apprenticeship, and Monkbarns was to go down in history as the last British commercial square rigger to suffer a mutiny.

Read on: Learning the ropes

Previously: Monkbarns apprentice

Written by Jay Sivell

June 4, 2010 at 3:10 pm

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice

Tagged with apprentice, Cotton Palmer Sivell, first tripper, handelsmarine, Isle of Wight & Sivell family, John Stewart & Co, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, marina mercante, marine marchande, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, square rigger, Tall ships, windjammer

A sailor’s life – 14. Monkbarns apprentice

Day after day and night after night there was nothing round the ship but the howl of the wind, the tumult of the sea, the noise of water pouring over her deck. She tossed, she pitched, she stood on her head, she sat on her tail, she rolled, she groaned, and we had to hold on while on deck and cling to our bunks when below…

From Youth, Joseph Conrad, published 1902

In 1912, the year Titanic sank with her band playing and the men deep in her engine room drowning to keep the electric lights blazing across the icy waters, Monkbarns was a throwback to a darker age.

Lit only by the smelly kerosene lamps that lurched in the cramped living quarters fore and aft, Monkbarns had no generator to winch cargo or weigh anchor, no auxiliary motor, refrigerator or Marconi. She had no great steam boiler growling in her bowels fed by a mountain of coal and a dozen stokers, condensing drinking water and drying wet clothes as it pushed them onwards across the sea. On Monkbarns the only sources of heat were a couple of cast iron bogey stoves and the coffee pot bubbling on the galley fire — until the cook chased you away. Down among the narrow bunks where the men off watch ate and slept, from the crew in the cramped fo’c’sle — where the waves boomed and crashed under the bows — to the officers in the cramped saloon aft, the ship reeked of wet oil skins, Stockholm tar, pipe smoke, and the dank straw mattresses known to sailors as donkey’s breakfasts.

It was a groaning, moaning, banging world 267 feet long and 23 feet wide, contained within a squat rust-streaked hull and dominated by three masts festooned with hemp and steel lines and wooden spars. Overhead, acres of weather-beaten canvas strained and slapped, tearing muscles and ripping fingernails to the bloody quick.

There was a raised deck fore with the anchor and a raised deck aft with the great wheel, open to the winds, and in between, set apart from both the men and the masters, two deck houses, one for the apprentice boys and one for the “idlers”: the cook, the sailmaker and the ship’s carpenter. Below them and sometimes stacked around them, was the cargo: wood or grain or coal or wool, but always “saltpetre” (nitrate) back.

When Monkbarns left Hamburg bound for Santos, in Brazil, on Bertie Sivell’s first trip, there were 14 men in the fo’c’sle, mainly Germans, Danes and Swedes, plus a Finn and an Austrian, and Bert was one of nine gangly apprentices in the boys’ house, conspicuous in their crisp new dungarees. Although the ship was Liverpool registered, only the boys and the young 1st and 2nd mates were English, and not all of them. At 16, Bert wasn’t the youngest aboard either. The senior apprentice was 21, but the Old Man – who wasn’t a bad old stick – promoted him out of the half deck as 3rd Mate on Christmas day, the log records.

The “Old Man” was a Scot, Captain James Donaldson of West Kilbride. Ship masters are always known to their men as the Old Man, no matter how young they may be, but Monkbarns’ Old Man was old indeed; a tall, thin, stiff, white-haired giant of 62, gaunt and craggy after half a century at sea. The son of an Ayrshire coal miner, he had started in coasting vessels at 17 and worked himself up the hard way through the fo’c’sles of deepwater traders.

By 1912, James Donaldson had been a master in sail for 36 years. But he had evidently not forgotten what it was to be young, for he kept a wind-up gramophone and a few records in the saloon for Sunday afternoons at sea, when his apprentices washed their socks and smalls. There had been a Mrs Donaldson, but the boys the Old Man trained did not recall her later when they themselves were old Cape Horners recounting for posterity their tales of the Monkbarns years. But they remembered their old master with respect and affection, as a “gentleman of the old school”.

And the old school in square riggers was tough. Officers, men and apprentices alike lived in two “watches”, working four hours on and four off day and night, night and day, except for two hours between 4pm and 8pm when they ate their evening meal, and swapped over. Their lives were measured in half-hourly bells, one to eight, telling through the day from black coffee and hard tack at 4am to the graveyard shift at midnight and on to 4am again. Week in week out, miles from land, through sunshine or fog, eight bells sounded the weary end of one watch and the bleary start of another.

In heavy weather, of course, there was no routine and no rest, only the imperious cry of “all hands!” and the urgency of taking in or letting out sails, dragging the yards round to change tack, and the kick of the great steering wheel aft which could break the helmsman’s arms and knock him flying across the poop.

Then, the teenagers clinging spray-drenched to the yards 80 feet above the pitching deck, fighting the bellying canvas with frozen fingers, swiftly learned the first rule of sail, which was “one hand for the ship, one for yourself”. There were no safety harnesses or carabiners. Like the Alpinists of their day, if they let go, they fell off, and once overboard they would swiftly be swept from view.

It was not always possible to turn the ship in heavy weather, nor to risk lifeboats and more lives. Mountainous seas can hide whole fleets let alone a bobbing head and flailing arms. Seamen often deliberately did not learn to swim, to ensure the end was quick.

Read on: Why would you?

Previously: Apprenticeship

Written by Jay Sivell

June 3, 2010 at 2:58 pm

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Sailing ship - Monkbarns

Tagged with apprentice, Captain James Donaldson, Corsars, first tripper, handelsmarine, John Stewart & Co, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, marina mercante, marine marchande, merchant navy, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, square rigger, Tall ships, windjammer