Archive for the ‘Isle of Wight & Sivell family’ Category

A sailor’s life – 68. Pyrula and the seamen’s strike, Curaçao 1925

Curacao, St Annabaai – showing the growing Shell refinery and tanker port in the Schottegat, from http://www.hetgeheugenvannederland.nl

The Shell oil tanker Pyrula – formerly the White Star liner Cevic, ex Admiralty oiler Bayol/Bayleaf and one-time decoy battleship HMS Queen Mary – left New York on 21st August 1925 for a new life in Curacao in the Dutch West Indies.

She was manned by a mainly Dutch skeleton crew of 16, including three catering staff and four South American “firemen” (stokers) being repatriated to Maracaibo in Venezuela and Puerto Rico. The young master’s only officer – and the only other Brit on board – was his Scottish chief engineer, George Andrew of Airdrie.

Pyrula was a 30-year-old British steamer with a nominal horsepower of 708 and a working crew of 50, but after four years rusting off Staten Island as a floating oil depot for the Anglo-Saxon Petroleum Company, she faced a final journey of nearly 2,000 nautical miles (3,500 km) down the east coast of the US and across the Caribbean at the peak of the hurricane season, to a small Dutch island possession 40 miles north of Venezuela.

The voyage, the crew agreement notes, was to last for a period not exceeding six months and the sailors were to stand by until the ship was safely moored.

Rocky, dry Curacao was booming. The refinery had opened in 1918 and by 1925 beside the growing tank park, water plant and pending drydock, a little wooden Dutch town had sprung up with its own club house, tennis courts and golf course. Every four days a “mosquito fleet” of tiny tankers poured in from Venezuela with the oil bonanza discovered under shallow Lake Maracaibo, and by July the Isla was processing 5,500 tons of crude a day.

Shell oil depot ship Pyrula – formerly the White Star steamer Cevic, Admiralty oiler Bayol/Bayleaf and decoy Queen Mary

As the oil trade expanded internationally, increasing numbers of tourist steamers too were calling at Curacao, which was handily placed for the Panama canal and the Pacific, and Willemstad was starting to rival Amsterdam for ships and tonnages handled.

Once again,Shell needed Pyrula for bunkering. From the main harbour in the Schottegat lagoon she would eventually move out and round the coast, east to Caracas Bay, as a floating oil pump to the bigger ships unable or reluctant to traverse the narrow St Anna channel between the pretty Dutch gables.

And there she would end her career, overseen by a new master, Willem Hendrikse, and his growing family from a comfy stone bungalow built at the waterside. No more Shell wives made their homes among the old panelled staterooms of the former passenger ship, with their electric fans and bells to the pantry.

Shell tanker Satoe - former Monitor 24, from http://www.helderline.nl

Hendrikse would eventually have two retired British steamers in his charge. Satoe was one of eight shallow-draft Royal Navy Monitor-class gunships bought up by the Curacaosche Scheepvaart Maatschappij after the first world war. As Monitor 24, Satoe had seen service on the Dover Patrol in 1918 and in the White Sea in northern Russia during the allied intervention after the October revolution, but the “flat irons” as the Dutch called them, were so unsuited to the tropics that the Chinese stokers used to faint from the heat in the holds, he said.

No ship’s log survives in the tidy blue cardboard folder in the National Maritime Museum archives in Greenwich, where Pyrula’s particulars for 1925 have lain crisp and apparently unvisited since the merchant navy records were carved up in the 1970s. The two pages for certificates and endorsements are blank.

Lloyd’s List reports she was one of 13 ships to leave New York that day, and the only one bound for Curacao. So the first hint of anything untoward on Pyrula’s last long passage south is a single undated line on the front of the crew agreement, where her chief officer/acting master, Hubert Stanley Sivell, my grandfather, has added: “Vessel in tow and not under own steam” .

Arrived in Curacao “to be a hulk”, reported Lloyd’s baldly on September 8th.

Twenty-four hours later the men were paid off – in dollars. A small fortune in dollars: $744, worth £153 at the ambitious new exchange rate set that April by the chancellor, Winston Churchill, when Britain disastrously rejoined the gold standard.

Although Pyrula’s crew agreement was the standard UK form, with the usual pre-printed scale of provisions (a pound of salt pork on Monday, a pound and a quarter of salt beef on Tuesday, preserved meat on Wednesday, plus lime juice “as required by the Merchant Shipping act”) and the usual puny 5 shilling fines for everything from possession of firearms to mutiny, Bert’s sailors that trip were not on standard National Maritime Board rates.

Instead of £9 a month – a rate controversially reduced from £10 only that August, and still not including clothing, bedding or time ashore – the Anglo-Saxon Petroleum company paid Bert’s seamen an astonishing $62.50 a month. £12 15s. His firemen were on $67.50, or £13 15s.

In fact the chief steward, H Mulder, 25, who had signed on as humble mess room steward at $50 a month and been promoted to $120 a month before the ship even left New York, was earning only £2 a month less than the Old Man himself – although young Captain Sivell did not advertise the fact. The column for pay against his name in the crew agreement is prudently blank.

Over in North Shields, in the north of England, the British crew of the Shell tanker Acasta – which was shortly to arrive off Curacao to collect Bert Sivell and two other “spare” Anglo-Saxon officers and take them home – would have been highly interested in the pay aboard Pyrula.

Acasta’s pantry boy, 20-year-old Albert Black of Dene Street, North Shields, was on £3 10s a month. He took a £1 15s advance when he signed up, probably to buy oilskins and bedding as he was listed as a “first tripper”, and set up a £1 15s “allotment” to his mother, which left not much. In Tilbury, forty days later, he would be paid off with just nine shillings.

Throughout September seamen with families had run the gauntlet of pickets and opprobrium at dock gates and railway stations up and down the UK to sign on for the new low rate. There were 1.2 million registered unemployed that autumn, but on £9 a month even fully employed seamen found themselves needing to apply for “relief” between ships.

A letter to the editor from a seaman’s wife in Hull in July demands to know how she is expected to pay rent, insurance, coal and “keep respectable” on £1 6s 3d a week. “Now then, all you sailors and firemen, buck up,” she wrote, the night before the cut came in. “What do you pay 1s weekly to your union for, and never one word of protest from none of you? Buck up some of you. Scandalous such treatment for a British sailor.”

By the time Bert Sivell paid off his crew in Willemstad with their wedge of dollars in the second week of September, British shipping was in chaos.

There were pickets on wharves from Southampton to Glasgow, and unemployed men from Cardiff to the Tyne waiting in tugs in the Bristol Channel and off the Isle of Wight to make up numbers as ships sailed shorthanded.

Across the Dominions thousands of British seamen had walked off their ships – 2,500 in Sydney alone – leaving steamers, mail and precious perishable cargoes, including refrigerated meat, maize and 15 million oranges, laid up from Wellington to Durban SA. Thousands of seamen were camped in meeting halls and private homes, fed by the generosity of local families and unions, while the Australian and New Zealand courts sentenced hundreds at a time to jail with hard labour.

And all for the sake of £1 and a vote.

The dispute had begun very low-key on August 1st, when pay on British ships was cut overnight by 10% in an agreement struck between the shipowners and Joseph Havelock Wilson, the president and founder of the National Sailors & Firemen’s Union. It was the seamen’s fourth pay cut in four years, but there was no vote on it, neither for the NSFU membership nor for men in smaller unions not represented on the official national Maritime Board.

When the cut was announced there had been protest meetings and speeches. Letters to local papers outlined the long hours and poor conditions aboard British ships (“only fit for seamen of an Eastern nation…”) and in Hull a disorderly NSFU meeting carried a vote demanding Mr Havelock Wilson’s resignation, which the union officers ruled out of order.

On “Red Friday”, July 31st, as the coal and rail unions were celebrating victory over the government of Stanley Baldwin, 200 seamen in Hull voted to strike.

The miners and railway workers were big hitters who had threatened a general strike over the mine owners’ plans to cut pay, (which was £3 a week in Staffordshire and up to 13s a day in Scotland) and faced with the prospect of the country being brought to a standstill Baldwin had backed down. He agreed to subsidise the industry for nine months, pending an inquiry (- which would lead to the general strike in May 1926, when the royal commission came back with a recommendation to cut the miners’ pay anyway, but by then the government had emergency plans in place – and volunteers on standby to drive buses and trains.)

But there was no similar support for the seamen. The NSFU stood by its sweetheart deal with the shipping companies, so the TUC – and even the breakaway Amalgamated Maritime Workers’ Union – considered the action “unofficial” and would provide no fighting fund. Within weeks, seamen refusing to sign on at the lower rate were deemed “unavailable for employment” and cut off from the dole.

Newspaper reports of the meetings of the workhouse guardians record debates about basic food relief, to prevent the wives and children of strikers “actually starving”. The men, it was agreed, should get nothing.

On August bank holiday weekend the Hull Daily Mail’s man at the dockside described the crowds of happy day trippers who piled unmolested onto the steamers Whitby Abbey and Duke of Clarence, despite the seamen’s strike. “There was no disturbance beyond a fight between two small dogs; a policeman on duty yawned continually, apparently bored with the inactivity of the ‘strikers’,” he sneered.

Up and down the country for the first three weeks of August ships sailed, and wherever men refused to sign on at the lower rate there were plenty of others hungry take their places.

Times were hard. The first world war had cost Britain her export markets. As the chancellor, Winston Churchill, wrestled with reparations and repayments, his overambitious return to the gold standard was having a depressing effect on Britain’s balance of trade. (Nations united by the gold standard, he had said that April, would “vary together, like ships in harbour whose gangways are joined and who rise and fall together with the tide…” Eurozone countries please note.)

Struggling to compete on price, British manufacturers cut pay. And kept cutting.

Even on the Isle of Wight unemployment was rising, from 1,000 in January 1925 to 1,538 by Christmas, but the situations vacant column in the local paper there (mainly seeking servants) was still three times the length of the situations wanted. Niton needed a gas lamplighter, the County Press reported, and a married woman teacher in Dorset had won a ruling in Chancery preventing the school governors terminating her employment, “even though there were single women teachers wanting for work”.

Seamen were largely casual labour, and even on £10 a month often could not lay enough by to feed, clothe and house a family during the growing gap between ships. To strike against the NSFU, cut off both from unemployment relief and union support, meant hardship.

By the middle of August it looked like the strikers might be starved out. But industrial relations took an unexpected turn when the first British ships started arriving in Australia after the three-week passage, and an energetic seamen’s union recently victorious in its own battle over pay and conditions took up the cause.

By the time Pyrula arrived in Curacao, the strike had taken a grip in the UK itself.

“Two thousand three hundred passengers, practically all Americans, booked to sail tomorrow morning from Southampton to New York on the White Star liner Majestic were at their wits’ end today,” the New York Times correspondent TR Ybarra cabled on September 1st, “trying to find out whether the Southampton seamen’s strike would force the Majestic to postpone her sailing.” Bristol, Hull and Liverpool were also affected, he said.

In South Africa, desperate fruit growers clubbed together to pay the disputed £1, just to get their oranges away. “The fruit interests are emphasising that for a matter of £70 in wages in this ship Roman Star £300,000 worth of fruit is being jeopardised, which if lost, will mean the ruin of many small producers,” the Western Morning News reported.

In Avonmouth, 30 boilermakers working on an Eagle Star tanker in dry dock downed tools. The San Dunstano needed enough work to keep 300 men employed until Christmas, they said, but they were being asked to just make her seaworthy to reach Rotterdam, where the Anglo-Saxon Petroleum company had already sent the US-built Ampullaria. With 400 men locally unemployed it was “not right to send three months work to the Continent”.

“A MILLION TONS HELD UP BY SEAMEN’S STRIKE”, shrieked the NY Times on the 17th.

With the country’s maize and citrus exports rotting on the wharves, the South African government tried to mediate – mooting a six-month inquiry, as put in place for the miners, but the shipowners said no. Union Castle began to recruit “lascar” crews in Bombay, but India and South Africa both protested – though for different reasons.

As well as their £1 back, and paid overtime, and an end to the NSFU’s closed shop deal with the ship owners, the strikers wanted a ban on cheap Chinese and “lascar” crews.

Asiatic seamen in the Strangers Home, West India Dock, London. Memorial University Newfoundland website

Wartime restrictions on enemy aliens living in the UK had been extended after the war, limiting employment rights for foreign nationals and barring them from certain jobs (including the civil service). The act had particular impact on foreign seamen working on British ships, and was encouraged by British trade unionists fearful of the cheap competition for jobs. [It was expanded again in 1925 by the Special restriction (coloured alien seamen) order, and even more shamefully not repealed until 1971]

Under so called “lascar agreements” big British firms like Union Castle signed up Asian crews as a job lot for a round trip, under a serang. They did not have to be paid British rates, because they were not signed in British ports, and they were expected to put up with grossly inferior conditions for reasons that can only be described as racist.

Acasta’s white British crew had themselves taken the place of 38 Chinese seamen and firemen who were signed off in South Shields on September 10 after 11 months’ service between Trieste, Malta, Panama, Montreal, Las Palmas and Marseilles.

These men were all registered to boarding houses in the same three streets in Rotterdam – Atjehstraat, Delistraat and Veerlaan, and their pay per month of the trip cost Shell even less, an average of only £3 a head.

Many Chinese had appeared in the tiny docklands peninsula of Katendrecht in 1911, signed up in secret by Dutch ship owners as strikebreakers to work the big passenger liners to and from the Dutch East Indies. They had no unions, only “shipping masters”, who allocated ships and rented beds in their boarding house between jobs.

The Chinese had a reputation as hard workers. They did not drink, were docile with their pipes and mahjong (“less troublesome than a white crew,” said Bert), and were willing to work for little pay.

They were also expected to eat less than a white crew, according to a typed “Scale of Provisions (Chinese)” tidily appended to Acasta’s crew agreement by Captain G. Croft-White. Although the same document shows fireman John Sow had to be left behind in hospital in Marseilles that trip suffering suspected beri-beri.

Shell’s Chinese seamen were entitled to 7lbs of beef, pork or fish each per week, against 8lbs allocated for white crews, and they got 10 and a half lbs of rice, instead of 11lbs of potatoes, biscuit, oatmeal and rice. They got less coffee, marmalade, bread, sugar and salt, more tea and dried vegetables, and no dried fruit, suet, mustard, curry powder or onions at all.

Capt Croft-White was clearly a belt and braces sort of chap, for above the scale of provisions is also gummed a paragraph from a printed document outlining the National Maritime Board’s absolute jurisdiction over pay board his ship, including its ability to retroactively impose cuts.

“It is agreed that notwithstanding the statements appearing in Column 11 of this Agreement the amounts there stated shall be subject to any increase or reduction which may be agreed upon during the currency of this Agreement by the National Maritime Board …”

Bert spent a month in Curacao, handing over and sorting out paperwork, but no letters survive. Only Acasta’s crew agreement shows that he was picked up “at Sea” on October 20th with two other British officers from Dutch lake tankers, and conveyed home to Tilbury.

He arrived back in Britain in November 1925. The strike was over. The seamen had lost.

From Australia came reports of violent clashes between police and British strikers in Fremantle, but after 107 days the men there too gave up and started trying to sign up for a ship home.

It was the loss of trade that eventually beat the seamen’s strike, as farmers and woolmen facing ruin eventually turned on the cuckoos in their nest. Lost, delayed and diverted trade was estimated to have cost £2 million. The shipowners claimed it was a Red Plot.

On December 8th, the Western Argus in Kalgoorlie, Western Australia, ranted: “The anti-British character of the strike was plainly shown by the action of the agitators who fomented it in Australia. They professed sorrow and indignation over the unhappy British seaman, compelled to starve on a miserable pittance of £9 a month, but they said nothing about the German seamen working for £4 4s. All their efforts were directed to holding up the British shipping trade, while foreign vessels were allowed to come and go unhindered…”

After more than four years away Bert hurried home the Isle of Wight for a rare Christmas with the wife he had not seen for a year and the baby daughter he had never met at all. His furlough pay as chief officier was £24 10s a month.

Read on: In Memoriam

Previously: Cabinned, cribbed, confined

A sailor’s life – 67. Cabined, cribbed, confined

Ena Sivell didn’t have the vote when she married her sailor sweetheart in 1922 aged 26. She didn’t have a home or signing powers on her husband’s bank account, and when she gave birth to their first child 3,000 miles away from her husband in a nursing home in Ryde, Isle of Wight, three years later he did not meet the baby until it was learning to walk.

Anglo-Saxon Petroleum (Shell) – having permitted the young first officer in charge of its New York depot ship Pyrula to keep his bride aboard ship with him for two glorious years – had ordered Ena off at the first sign of pregnancy and she took her bump and her souvenir Broadway programmes and went back to the town where she was born, to make a temporary life in rented rooms, dependent on her father-in-law for paying her bills until her husband came home, which tried her sorely.

But Bert stayed on. And on.

Tradesmen’s families like Bert’s and Ena’s did not have telephones, and communication between husband and wife was by letter – two weeks out, and two back by the great transatlantic liners that swept to and fro between Hamburg, Southampton and New York in the days before air travel.

The baby was born in March, too weeks overdue. Ena – flat on her back in bed with her knees tied together, in the approved treatment of her day for a torn perineum – sent off a telegram to the States.

Bert was hugely relieved and rang all their American friends at their places of business from the ship’s phone line, fixing himself up with dinner and a trip to the Hippodrome with Ena’s chum Florence in the process.

His first letter reached her two weeks later. “I’m really a little disappointed that a girl has come along,” he wrote, with jaw-dropping insensitivity. “I would have liked a boy. But as Mrs Franke Snr told me Monday – I cannot change it now!! Mrs Mercer says I must try again …!!”

And he was no better at reassurance for his stretched little wife’s sagging self-esteem. Dismissing the rupture in his next letter with all the carelessness of a man who has never tried to pass a watermelon, (“Never mind, you’ll soon be alright again”), he added: “I cannot quite agree with the doctor that you are decidedly on the small side, my dear, although if he says so we ought to be glad you are no bigger.” Nearly 90 years later I still want to hit him.

Bert Sivell was a conservative, with a big and little C. An only child who had run away from home aged 15, he had grown up at sea, far from “decent girls,” as he put it, except for the Mission families in Australia, and the master’s daughter, Jeanie Donaldson, who made one trip with Monkbarns as stewardess in 1917. He didn’t approve of women shingling their hair, or wearing trousers.

His was a man’s world. A month after his daughter’s birth his letter home was full of the five new oil tankers that Furness Withy had ordered from German shipyards. They had offered British firms substantially more to take the work, he reports. “But owing to the labour conditions, the British firms could not take the offer. I am rather surprised that the ASP have placed orders for four new tankers* with British firms, because they are paying through the nose for them,” he wrote.

“By the way, dear, you have still not told me yet what the baby’s name is going to be…”

If the baby had been a boy Ena had suggested John Thomas, which Bert had vetoed by return of post. It was slang for penis, familiar to readers of DH Lawrence’s novel Lady Chatterley’s Lover, the third of three versions of a story that Lawrence would publish three years later in 1928, although it was 35 years before it could be openly sold in the UK. “The name John Thomas is unsuitable,” wrote Bert, “although you should not know what it means.”

When he finally got home in November, he carried in his trunk a well thumbed copy of Dr Alice Bunker Stockham‘s pioneering sex guide Karezza, recommended by a chum and bought at Wanamaker’s wonderful bookstore in New York. He had read it cover to cover.

They had also acquired Dr Marie Stopes equally controversial Married Love, which he had persuaded a reluctant Ena to have sent to the house in a plain brown wrapper.

“When I get home again we are going to be as happy as happy can be, aren’t we, darling?” he had written. “Especially with this new information I have gathered. We were going at things in a wasteful sort of way before…”

Read on: The seamen’s strike 1925

Previously: Clam, a moment in history

*[These would be the 10,000 DWT Bullmouth, Bulysses, Patella and Pecten; another six orders went to Dutch yards]

A sailor’s life – 63. To have and to hold, Pyrula 1922

The visiting tanker captains had egged him on: “Get married,” they said. “Grab the chance while you can.”

Bert Sivell, writing from the master’s quarters of his first “command” – a redundant passenger steamer serving out her days as an oil depot ship off New York in 1922 – took the plunge. “Come out and marry me,” he urged his love, far away in the UK.

The American master of the oil tanker Pearl Shell was the envy of all the Shell masters that winter. He had his wife in Philadelphia, an hour and a bit away by train from the ship, and he trotted off home every night.

“He told me I was a fool for not having you over here months ago,” Bert wrote. “He had not seen his home for two years before he came here, and had not seen his wife for eight months, although she had gone over to ‘Frisco and elsewhere in the States whenever he came to US ports.”

“Come out and marry me,” he urged. “Gossips in Ryde will be busy about conventions and rubbish, but don’t let that worry you. Trust me.”

So the little milliner from Ryde boldly left the town where she was born and caught the White Star liner Homeric from Southampton in December 1922, carrying in her trunk the homemade trousseau she’d been stitching for three years. Her young man gave her £60 of his savings – which was more than she earned in a year – and for half of it she shared a windowless cabin in second class with a girl called Florence Ayers. (No point paying for a port hole, Bert had said knowledgeably; at that time of year the crossing would be too rough to open it anyway…) Florence and Ena were to remain friends for the rest of their lives.

She’d thought it was wishful thinking when Bert first raised the idea in February, in a throwaway line about needing a secretary for all the paperwork the Asiatic Petroleum office was throwing at him.

She had expressed pity that he was darning his own socks. “You had better come over right away, my dear,” he wrote. “I have a whole pile of mending of all sorts, even my jacket is falling to pieces, but I have had no time lately.”

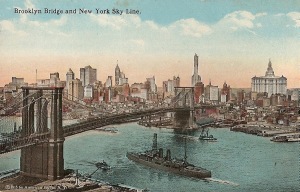

Bert was marooned a mile off Brooklyn, pumping oil through the worst snowfall the US east coast had seen since the 1880s, and fighting for access to the motor launch which was his lifeline to shore.

Across New York bay the great transatlantic steamers came and went, carrying his mail and knocking Pyrula about in their wake. He had nothing much to write about except work.

“I have not been inside a picture house since Christmas, although I fail to see what that has to do with the Asiatic anyway,” he wrote, aggrieved, after rumours in the office that he spent too much time ashore or visiting other ships. “They all forget that our day consists of 24 hours and even if we are not actually working, we live in the midst of it and that is as bad. All last night I spent on deck with the worry of being helpless if she broke adrift and today (Sunday) the 2nd Engineer and I put in four solid hours in the snow cutting out the burst steampipes ready to be sent ashore tomorrow morning. If their ideas were in operation we’d need a wooden crew.”

But in March it all changed, when Pyrula was allowed to chip out her frozen chains and come ashore to Pier 14, Stapleton, NJ. Suddenly Manhattan was only a ferry ride away. They had neighbours and mains electricity and Bert was promised a telephone. He began to enjoy the job.

Out of the blue, the Asiatic announced they might be wanting him to stay on. For another year. In great excitement, he wrote to Ena.

“It would be detrimental to my career in this company to refuse to stay. So, my dear, the point is this: if such an event as the postponement of my leave should occur, will you be willing to come over here and get married and live aboard the ship?”

He had it all figured out, the British consul, the ceremony. He would pay for her passage over. It would be cheaper for Ena, he said, “considerably cheaper, because you can dispense with your wedding dress…”

Bless her, Ena took it on the chin. After months planning a wedding in Ryde, checking rental properties and buying household linen, the letter cost her a sleepless night, but she was game. Her friend Vi Trent had just got married and moved to Leeds, and she’d got quite fed up of the newspaper coverage of the Princess Mary’s sumptuous wedding the previous month. She consulted a fortune teller, who saw a journey and a long life (Ena did not inquire about Bert, perhaps just as well), and then she set about acquiring a passport.

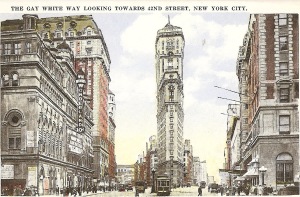

Bert kitted himself out in new clothes, American style — straw hat, wasp waisted suit and new tie, and took himself off to explore the sights of New York, bombarding her with postcards. He also repainted the ship from stem to stern, hung out the flags for her birthday, and began buttering up the local vicar with regular Sunday church attendance.

At numbers 32 and 110 High Street, Ryde, their parents were less happy. “I can understand your people kicking a bit against the idea, because you are a girl and need looking after —!! (ahem! —!! don’t smack me),” Bert wrote. “But why my parents should object I don’t know. I suppose it is because I am the only one.” Bert’s dad had written an angry letter, the gist of which appeared to be that Bert had not asked his consent to marrying abroad – although it probably had more to do with them only having heard of their son’s plans from local gossip. “I wrote back and said that as I was marrying you, I considered you were the only one I should consult.”

Shell too was not thrilled. The group permitted overnight visits by officers’ wives in port – and their agents in New York, Furness Withy, even allowed wives (though again, only officers’ wives) to accompany their husbands on short voyages. But Bert Sivell had grown up in sail.

Generations of masters’ wives of all nations once made their homes in the saloons of their husbands’ sailing ships, generally doing a lot of sewing and letter writing, but learning to take a noon sight or a trick at the wheel, just in case. They were there because shipboard discipline depended on masters remaining aloof – even from their junior officers – and because sailing ship masters were small businessmen often with a financial stake in their ship and no spare cash for idle investment in a house ashore. The wife’s comfort was not a prime consideration. “I have occasionally had to hint to him that my name is not down in his ship’s articles…” wrote one emancipated captain’s chattel in 1873.

It seemed a matter of course to Bert that Ena should live aboard Pyrula with him. A perk of the job. Vivid in his mind was the fate of the chief engineer who had arrived in New York with him the previous year to be met by the news that his wife had died, leaving his four young children in the sole care of the eldest, aged 14. “I shall probably never get such a long spell in port again.”

And he got his way. On 8th November 1922, the head office of the Anglo-Saxon Petroleum company in St Helen’s Court, London, cancelled the home leave due to the young officer-in-charge of the oil tanker Pyrula at the urging of its partner, Asiatic Petroleum, and granted permission for his bride to join him aboard – at 3/6 a day. “As you are aware, this procedure is not a rule of the Company and you should, therefore, regard it as a concession,” said Shell, firmly.

A month later, Bert was on the quay when Homeric pulled in. By noon he and Ena were bowling down Broadway in a taxi, heading for the Staten Island ferry and the church of St John, Rosebank, where the vicar was standing by to wed them. By two o’clock they were onboard Pyrula, man and wife. Bert even organised a tiered cake, so that Ena could post slices home to her friends – proof that the proprieties had been attended to.

The wedding photograph shows a rather lumpy young woman smiling shyly in a sensible two-piece suit and a feathered hat that dwarfs her groom. Bert, ramrod straight in his best uniform, beams stiffly, his mouth tight shut on his bad teeth.

They got themselves a dog called Buster and a black kitten they christened Microbe, and they made a home together at Pier 14, taking in the shows and the sights of New York whenever Bert’s work permitted. Vaudeville was on its way out, elbowed aside by the flickering silver screen. But Ena loved the vast and glittering Hippodrome, on 6th Avenue – with its performing seals, midgets and minstrels, and she acquired a stack of 10 cent programmes, with their adverts for fashion houses and ice-cream and perms and even Perrier water. They went to see Hollywood’s darling, the silent movie heartthrob Douglas Fairbanks, in The Thief of Bagdad at the Liberty Theatre on 42nd Street as soon as the film opened in 1924, and they made friends ashore, socialised and for almost two years just enjoyed being together.

And then, Ena found she was pregnant and abruptly the honeymoon was over. Ena packed up her playhouse programmes and her souvenir guides of New York and went home. Anglo-Saxon did not allow children on the ship and she had to go back to the Isle of Wight, to set up house and have the baby, alone. Bert had to stay. He did not see his daughter until the baby was more than a year old. Though they did not know it, most of their days together were over.

Every Sunday for the rest of his life he wrote to Ena, date stamping the envelopes so that she might read the letters in order, and every year on December 9th a telegram would arrive from somewhere in the world, reading “Shimmer shine. Bert.” This, deciphered out of nautical telegraph code, meant: “Another anniversary of our marriage. How happy we have been, love”.

There was no telegram in December 1941.

# # #

Read on: Majestic and her sisters

Previously: New York, New York

2013: The Fishwives Choir – seamen’s widows to release fundraising single

A sailor’s life – 62. New York, New York

America had been “dry” for eighteen months when the Shell oil tanker Pyrula dropped anchor off New York in autumn 1921 under the stern, sober eye of Miss Liberty.

In Times Square legitimate restaurants and bars had closed, and special investigator Izzy “the human chameleon” Einstein and his straight man Moe Smith were already hundreds of arrests into their extravagant career as prohibition agents – sniffing out under the counter liquor in a variety of plausible disguises, from expansive cigar salesmen to thirsty longshoremen.

It was the age of the speakeasy, just “ask for Joe”. There were several thousand underground drinking dens in Manhattan already by that winter, varying from dingy doorways behind which tired bar girls pushed illegally stilled liquor and the lure of sex, to glizy private social clubs peopled by flappers and dapper men in spats. Here, the cocktail grew up, to hide the taste of bad booze. It was the era of jazz, and racketeers and movies.

But the British crew on Pyrula were not destined to see much of the bright lights of the Big Apple. By the time the first snows fell that winter, Bert found himself moored in the open roads off Brooklyn, three miles from the nearest landing stage, as officer-in-charge on a floating fuel pump.

Pyrula was a big ship – 520ft long and “as wide as Union Street,” as Bert wrote to his people back home in Ryde, on the Isle of Wight. She had started life as the White Star steamer Cevic, one of the “cattle boats” carrying livestock and immigrants between the US and Europe. She had been requisitioned by the British Admiralty in 1914 and she saw action as a decoy warship – a dummy Queen Mary, with cylinder tanks built into her holds to carry oil. The Anglo-Saxon Petroleum had bought her after the war and Bert had joined her as Mate in Barcelona in September 1921.

They were bound for New York via Tampico, Mexico, through the hurricane belt. There were 70 officers and crew aboard, all housed over three decks amidships, and his room was the most luxurious he had ever had in all his ten years at sea. It was the size of the sitting rooms in the houses along the street where he had grown up, with electric lights, a fan for hot weather and a bell to the steward’s pantry.

The master was an old sailing ship man who was delighted to discover his new first officer had served his time in sail.

Captain Baxter was nearly 60 and had been 20 years in sail before he and his ship were taken over by Shell. Dolbadarn Castle had been demasted and converted to a motor ship, Dolphin Shell, and Baxter had just returned from three years’ service with her in the Far East. Pyrula was his first steamer.

He knew the ship to which Bert had been apprenticed at 16, and had met the captain, James Donaldson, in ‘Frisco in 1893. Bert for his part had not a bad word to say about the gentlemanly old sea dog — not even when he brought aboard two tiny chinchilla monkeys, which ran amok among Bert’s fresh paintwork with dirty paws.

“Every evening after tea the old man comes up on the bridge and we have a yarn about the old sailing ship days,” he wrote home in his weekly letter to his waiting sweetheart. “He is really very interesting. Some of the places he has taken his ships need considerable skill to get in. He bought a couple of monkeys in Gibraltar. They are the queerest looking things that ever I saw, very lively and climb all over the place. One has a special liking for my shoulder and when walking up and down the bridge this little article will suddenly spring off the top of a door and land on me. They are quite small, not much bigger than a squirrel. I don’t know how they will stand the cold. We have also a couple of cats this trip, stowaways from Gibraltar.”

The orders had been to collect a cargo of oil from Tampico in Mexico and take it to New York, where Shell was keen to grab a slice of the city’s booming 796,000 barrel a year bunkering fuel market. With the US price of oil off the wharf at $1.85 a barrel, the group’s accountants had worked out that they could make over a dollar a barrel profit shipping it up from Mexico, even including freight and handling and the Mexican government’s 14 cents a barrel tax.

For some time, the directors had been casting about for a site in New York harbour to build a shore depot with fuel tanks. In February 1921 proposals were “laid on the boardroom table”, as the company minutes show, to buy and develop a 22 acre site which had been found on the New Jersey waterfront opposite Staten Island. It needed dredging and a pier, and was to have cost an estimated $665,000, but by late summer the scheme had been rejected amid doubts over the vendor’s title to the land and it was decided instead to make do with a cheaper option: an elderly depot ship and a young officer-in-charge.

That August Bert was offered the job – and the prospect of a pay jump from £26 to £35 a month, which was most welcome to an ambitious chap saving up to marry his girl as soon as his first leave was due, in eleven months’ time. He was 26, and had been with Shell for two years.

At home, unemployment was rising. Demand for British coal, steel and woollens slumped after the war. The empire’s markets were in tatters. On both sides of the Atlantic ships were being laid up. Men were being laid off. The old industries struggled, and in the midst of it all a much younger industry, oil, grew strong.

In ten days after leaving Gibraltar they sighted only four ships, even along the US coast. “It shows that the Yankee trade depression is just as heavy as our own because in normal times this coast is alive with shipping, mostly American coastal traffic it is true but even coastal traffic means work for someone,” Bert wrote.

Bert reported 600 vessels idle in Newport News, VA. Worse than any port in England, he said. And New York and Philadelphia were said to be the same.

The men who had deserted the Red Duster for big Yankee wages during the war were on the beach too. “The few American ships running will only carry Americans. None of the crews of British vessels calling here ever desert their ships now, so there is no chance of the stranded ones getting away.”

He had scant sympathy. He had served the war in sail, running saltpetre from Chile for the munitions industry and Jarra wood from Australia for pit props. He had endured low pay, bad food and rough men, but it had taught him his trade and in the summer of 1919 he had been very happy to exchange his crisp new sailing ship master’s “ticket” for a dry berth on oil tankers and three square meals a day.

He was a qualified captain, but it had taken him nine months to climb back to first officer. Officer-in-charge of an oil depot ship was another step up, but it was hard work.

Some weeks Bert was on his feet for 63 hours at a stretch, taking oil from the tankers that ranged alongside them in the deep roads, and discharging it into smaller lighters that tendered among the big ships along the Chelsea piers where the White Star liners and Cunarders docked. Tossed by the backwash of the great Atlantic passenger ships that brought him his mail, far from the bright lights on shore, he watched the immigrants arriving from the old world, huddled at the railings for a glimpse of the new.

There was no telephone aboard. If he needed to talk to the agents he had to take the motor launch ashore and phone from the quay. He visited the office in Manhattan twice a week, taking in lunch at his favourite Chinese restaurant up town. It had an orchestra and dancing, which he watched. He loved jazz and occasionally took in a show or a movie. If he enjoyed other diversions, he did not mention them in the letters and cards he fired off to his fiancee, Ena Whittington, on the Isle of Wight.

Marooned on Pyrula, a mile offshore, with a mainly Irish and Scandinavian skeleton crew of fourteen, prohibition made little impression on Bert, although he was not himself was not averse to a tipple, as he admitted as he nursed himself through the ‘flu that laid waste to New York in January 1922. For several days he had lived on hot malted milk and rum — “shocking, and in a prohibition country too,” – and many a ship master shared a dram of the real McCoy with him after the oil had been pumped across, for it was a cold job.

When a Sinn Fein flag, ensign of the Irish free state, appeared on the bulkhead in the crew quarters he prudently ignored it, but when one of the firemen (stokers) succumbed to what Bert suspected were the effects of “moonshine” he had him packed off to hospital ashore, smartly. The authorities tended to ask unwelcome questions about where booze had come from. But the patient was outraged to discover his pay was stopped while he was laid up and threatened to sue. On discharge he refused to return to the ship, and he died of alcohol poisoning in another hospital two weeks later, one of thousands of victims across the US. (“So that settles his lawsuit,” wrote Bert, unsympathetically.)

Shell tanker Pyrula, master's sitting room, 1922 - time exposure with cat in foreground, probably growling

By the beginning of February the snow was 2ft deep on the deck, and all the pipes were frozen up. As the ice melted, it trickled into his rooms in 26 places. Between ships, the stowaway little black cat that had survived the hurricane was his constant companion. It followed him around the deck like a dog and sat on the safe in his room as he worked, growling at its own reflection in the wardrobe mirror.

Unable to get ashore, Bert’s pay had never quite reached the £35 a month he had been promised; the ASPCo deducted meals at 3s 6d a day for each man. Overtime rates had been abolished the previous October (“though we still have to work overtime, or face the sack…”) and in March, the pay itself was cut by £2 4s a month, the second time in a year. In May it was to go down a third time, they were told, by £1 2s. “We shall soon be going to sea for our health,” he wrote dolefully, but to his surprise only one of his crew quit.

By now, Bert was counting the months until his leave, when he was to go back to the island to get married and set up a home of his own ashore. He had been at sea since he was 15 and never home for more than a few weeks until the summer he’d met Ena.

However, at the end of March, all his plans were thrown into the air. After months at anchor, Pyrula was moved to a permanent berth beside a pier on Staten Island. Pier 14, Clifton, had power lines from the shore and Bert got a telephone in his room. Trains and trams ran past the pier gates straight to the Manhattan ferry and the shows, and in the evenings after work, he was able to take a walk.

By late spring Bert was writing chattily home about the 25 cent movies, the talent nights at the local palais and several sightseeing trips he’d enjoyed in a friend’s automobile.

Life on the pier was a bustle of activity, with “noise and all sorts of things going on” day and night. One week a small steamer turned up and discharged a cargo of cork, lemons, sardines, and almonds into the shed beside the tanker. All day the scent of lemons hung strong about the wharf. Pyrula had just taken on coal, but Bert uncharacteristically left his ship black with dust from stem to stern rather than risk dirty water running off and spoiling the fruit.

Some shore life diversions were less welcome: one night they were burgled, together with the Standard Oil tanker lying beside them, and a four-masted schooner nearby. While Bert slept, the thief or thieves bypassed several night watchmen and the catches on all the doors. “When I woke up at 6am I found my room like a shambles and clothing lying around everywhere.” They had taken his watch, chain and binoculars, plus an overcoat from the steward’s room and shore-going clothes from the other tanker, but missed Pyrula’s pay roll, which was in Bert’s safe, and a gold watch he had brought as a present for Ena.

At home, Ena was busy sewing for the wedding, amid much envy and ribbing from her mates at the milliner’s in Ryde where she now worked. On Pier 14, Pyrula shifted record quantities of bunker oil, the young officer-in-charge was mentioned in letters to head office, and Bert made a momentous decision. His leave was fast approaching. He’d been away three years. He was entitled to go home. But it was rumoured that the agent wanted him to stay.

“If I am ordered to remain here it would be very unwise to kick,” he wrote. “Because I would only prejudice my career in this company.” He would lose Pyrula and his next ship might be out east, where Ena could not follow.

“Come out and marry me,” he telegrammed.

Read on: To have and to hold, Pyrula 1922-1924

Previously: Hurricane at sea

The White Star steamer Cevic disguised as the battleship Queen Mary in 1914, note dummy first and third funnels with no smoke

A sailor’s life – 61. Hurricane at sea

Hurricane damage, Tampa dock, Florida, October 1921 (Photograph: Burgert Brothers collection, Tampa)

“During the afternoon the wind increased. My word, it did howl, it just shrieked past us and the rain came down in torrents unceasingly. A mountainous sea rose and the Pyrula, big ship that she is, was tossed around like a cork. Soon after 4pm four 10 gallon drums of coal tar got adrift in the fore ‘tween deck and then the fun commenced.

“She was capering around so much that she just threw them clean out of the lashings. The bosun managed to rescue two before they came to harm, but was a bit late with the other two. The bungs came out and oh! what a mess. Coal tar spread itself all over the deck and ran out of the scupper holes from where the wind whirled flying tar all over the place. Then, a heavy plank that was chocking off some drums of red lead and other paint in the lower fore peak collapsed, while in the top peak a barrel containing 500 weight of white paint got adrift. During a mad career around the deck it spilled half its contents and collided with a 10 gallon drum of black, so there was another queer mixture.

“It was impossible through all that rain to see further than the forecastle head. We were nearest the centre of the hurricane around 7 pm, after which the barometer began to rise. The sea was terrible – huge waves coming along from all sides. The vessel was buried in spray, but she did not ship a single sea until 7.30pm when she took a beauty. It came aboard practically the whole length of the vessel at the same time. One lifeboat was smashed, the galley skylight was washed off, several awning spars carried away and two beams buckled on the fore deck. To give you an idea of the size, let me say that the boats are all 45 ft above the water. A lot of water went down the engine room skylights and I expect some of the engineers thought their last day had arrived. After that things began to improve, although there was a tremendous sea running for 24 hours afterwards. When daylight came next morning I found my poor lifeboat sitting on top of a steam winch.”

Bert Sivell to Ena Whittington, from the Anglo-Saxon oil tanker Pyrula off Florida, October 1921

The unnamed hurricane, a category 4 with winds of up to 140mph, landed off the Caribbean near Tampa on 25 October and swept eastwards across Florida, causing widespread destruction as it slowed, although only six people were killed. Florida was still a sparsely populated fruit growing belt. Aboard Pyrula, rolling and twisting 150 miles away in the hurricane’s wake, one of the two stowaway kittens they’d picked up in Gibraltar was lost overboard.

Read on: New York, New York!

Previously: Ships that pass in the night

A sailor’s life – 51. The wives’ tale

“Why do you want to know about the seamen’s wives?” the librarian’s voice had asked down the phone at one of the bigger maritime museums. “All they had to do was sit back, collect the money every fortnight and mind the children. Actually, I knew one who didn’t even do that – she went out every night to the pub, parked her kids with neighbours. She did not bother to pay the mortgage either and eventually the house was repossessed. She was a real character. Why do you want to know about the wives?”

The sea is hard on sailors’ wives. The money is good, but loneliness is in the job description. Even nowadays, marriage to a sailor means papering your own ceilings and putting up your own shelves, and endless missed birthdays and Christmases, but once upon a time eyes would slide sideways at the sight of a mother holidaying alone, and although her children might find playmates on the beach, fellow hotel guests kept their distance. “They presumed my husband was in prison,” one trim captain’s wife confided of holidays in the 1960s, when I – having drawn a blank among books and archives – set out to learn about my grandmother’s life from the women still living it.

“My husband was terrible at writing,” another former master’s wife admitted, cheerfully. “He wrote to his mother more often than to me.” And she told of the parcel of letters that had turned up with the post one day many years ago. They were her letters, written to her husband at sea care of various ports but found washed ashore on a beach near Dover. They were returned to her, carefully dried and pressed, with a covering letter from the finder – desperately concerned that the condition of the letters meant bad news. She looked pointedly at her husband, a senior BP man, who grinned at me, unabashed. “Well, we had to keep our luggage to a minimum for the trains,” he said. “So when we got to the end of a long trip, a mile or two into the English Channel, we used to tie up the letters and dump them over the side. Less to carry…”

In Ena Alice Whittington’s day, during the last years of sail and the rise of oil, marriage to a foreign-going seaman meant a lifetime apart, measured in weekly letters that arrived months late. Bert Sivell navigated by sextant and in 1940 Ena was still waiting to be connected to the ‘phone. In Ena’s day, marriage to a merchant seaman meant lugging your own coal and raising your children alone for years between a husband’s visits – three years, in her case, for that was how long Shell signed for. In between, the men might spend years coasting out in the Far East – too far away for their families to follow. And when they did happen to call at a British port, only officers were allowed to have their wives aboard. Children were discouraged on oil tankers.

Bert Sivell’s letters reveal that when he left home for the last time in December 1940 to return to his ship, his ten-year-old son had only met him four times and that, counting all the days and hours they had together, my grandmother’s marriage amounted to barely three years.

Bert’s letters filled a sea chest. Unopened for half a century, forgotten snaps and faded cuttings slipped out from between the crisp sheets. A hand drawn menu, a page from a magazine, an unfiled receipt. Bert’s letters, from all over the world; hundreds of them, telling first of birds and whales and floating mines and counting the days and weeks until he might see his love again, and then later of tonnages pumped and tanks cleaned, delays and disputes, and lonely glimpses of the beloved island as his ship passed by in the night.

Beneath Bert’s letters the chest we found beside my grandmother’s bed was empty. There were no letters from Ena. The firelight sketches Bert had laughed over, the snippets of poetry, news of friends and the daily trivia of coughs and colds in the little family he replied to were all gone. Had he not kept her letters? It seemed oddly unlike the man who emerged from the mass of precise, tight written sheets.

Had Ena destroyed her own letters during her forty years of widowhood? Or had she given them up earlier, for the war effort? Hers, but not his. During the second world war, the slimline Isle of Wight County Press had constantly exhorted its readers to turn in their paper. Either way, it seemed the crumpled, bow-legged little woman I had known, living on the hill in the house full of nick-nacks where nothing might be knocked or moved, had kept her youth in a sea chest by her bed all those years and we never knew. Too late, I wanted to know what her life as a sailor’s wife had been like.

The stories I could not find in any book poured out of the “watch ashore”, and their children. “My mother hated the sea…” “My mother said if she had her time over, she would never have married a seaman…” “My mother loved the ships…”

This is my grandmother’s story too.

Read on: War and peace, Donax 1919

Previously: The girl next door

A sailor’s life – 50. The girl next door

They also serve who only stand and wait

Milton, Sonnet 16

It was high summer 1919 when Bert Sivell came home to the street where he grew up, in Ryde, on the Isle of Wight, after nine years away at sea and met Ena Alice Whittington. Young people everywhere were dancing. The war in Flanders was over; the Spanish ‘flu a distant nightmare. Men were pouring home, and those who had survived the mud and blood and gas of the trenches wanted to forget. In northern France, gangs of Chinese coolies were collecting up and burying bodies, and in the skinny columns of the Isle of Wight County Press the list of local sons and fathers “killed, previously reported missing” began to lengthen.

Letters to the editor might voice concern that there were no jobs for disabled ex-servicemen, but there were pages and pages more on the rallies and regattas, and sports days and agricultural shows and tea dances and tennis.

By August bank holiday the island and the beaches were heaving. In Ryde, there were burlesques on the pier, Ellen Terry in the picture house and bathing machines strung out among the waves. There was jazz, and picnics and sunshine, and it was good to be alive.

Ena Alice Whittington was 23 and overshadowed by a prettier, livelier younger sister at home when she was introduced to an old school chum of her brother’s, a neighbour, that month during her scant summer break from the workshops of a large fashion emporium in genteel Tunbridge Wells.

Ena was a milliner, one of three daughters of a tailor with a shop at the narrow top end of Ryde High Street, where socks and ties hung in the window side by side with flat caps and homburgs. Unlike her Auntie Clarrie, who still lived with grandpa Whittington round the corner in Arthur Street, making straw hats for 2/6d – Ena had left the town where she was born and the extended family on the Isle of Wight, to make big hats in velvet and silks for Kentish ladies of conservative tastes. She’d wanted to be a pianist, but she had to leave school at 14 to work.

Ena was a plain girl with a long face, and neat hair pulled into a conservative bun. Bert was short and weatherbeaten, with empty gums after years on salt beef and pork, and a wooden smile because he kept his mouth clamped shut to avoid showing the gaps.

Within a month of meeting they were engaged. By letter.

Fred Whittington and his youngest daughter outside their gent's outfitters on High Street, Ryde, Isle of Wight, about 1902

A questionnaire filled in by 130 British merchant seamen in the 1970s* revealed that two thirds had married local girls living within ten miles of where they, the men, had grown up – which was not necessarily near the sea. Although a small majority of ship’s engineers were from big cities or ports, only half the deck officers had any prior link to the sea.

Of the 59 wives in the survey, all but three had had a career before marriage, and most had set up home somewhere they might have daily contact with their mothers or sisters. The pace of their married lives might be dictated by the business of their husbands’ ships – a trawlerman is ashore more often than an oil tanker man, a passenger liner more predictable than a cargo carrier – but their social lives revolved around family and their own friends. (Although most kept in touch with at least one other seaman’s wife if there happened to be one in her area, they said.)

The men had chosen the sea long before they thought of a wife or family. They were apprenticed in their early teens and spent their formative years far from home, sharing with strangers in cramped, noisy spaces much like boarding school or prison, where each task had a rank, and a rigid caste system dictated who lived fore or aft, who above deck and who below, even who ate with whom and what and where. In the girlfriend stakes, engineers tended to fare better than deck officers, as their apprenticeships were shore based, in the dockyards, so they shipped out later and thus met more young ladies before they went. The survey found engineers also tended to marry younger, be less middle class and spend more time with their relatives and neighbours when ashore. But then, when Bert Sivell was a boy, engineers ate segregated from both officers and crew, and even chief engineers did not make captain.

Of the men who rose through this system, the middeaged master mariners of the merchant fleet, Rear Admiral Kenelm Crighton wrote in 1944: “Their small talk is generally nil, their speech usually abrupt, confined to essentials and very much to the point… They uphold discipline by sheer character and personality – for their powers of punishment under Board of Trade Regulations are almost non-existent.”

Bert had been away for a third of his life by the time he came home that summer of 1919. He had left a boy and returned a man, with his master’s ticket in his pocket and good career prospects. Ena was bright-eyed and gentle and not too scary, being from just up his street. She was also a skilled worker, independent and capable of managing money. She had begun as a shop girl in Ryde but had left home to train as a milliner, which was a respectable occupation for a small tradesman’s daughter, although it did not pay very well and in the slack times – like summer, for hats were seasonal – hat makers were often laid off and expected to return to their father’s household.

Ena was perfect sea wife material, and before she and Bert had so much as held hands he cycled from Ryde to Tunbridge Wells and pledged himself to her, with her parents’ blessing.

That Ena Alice knew nothing of the sea was neither unusual, nor considered a problem.

Read on: “Why do you want to know about the wives?”

Previously: Clan Line, or Shell

*I only ever found one survey on seafarers’ wives; historically, neither owners nor unions have seemed much concerned with the impact on the “watch ashore“. If there are other studies, I’d be interested to hear.

A sailor’s life – 49. Clan Line, or Shell?

Bert Sivell, formerly Mate of the sailing ship Monkbarns, joined the Anglo-Saxon Petroleum Co (Shell) in autumn 1919 with a crisp new Master’s ticket in his pocket barely a fortnight old.

He was 24, with hands-on experience of shipwreck, war and mutiny, but he signed on as humble 3rd mate in the oil tanker Donax for £18 5s 6d a month, ”all bedding, linen and uniform accessories to be supplied by the Company”.

He had arrived back in Britain just in time for the national peace day celebrations that July – parades and bunting and industrial unrest. After nine years at sea studying by kerosene lamp between watches, sitting scrambled tests in ports around the world for hurried promotions, he was to spend some weeks with his parents on the Isle of Wight, attending college on the mainland each morning, and relaxing at the weekends cycling through the country lanes or tramping miles across the chalk downs with friends. (“Girls, of course,” he wrote to the girl who would be my grandmother.)

When he graduated top of his class with 89% marks after seven weeks, he was offered a job immediately, as 4th officer on a steamer departing for India that night. But he turned it down, saying “he was on holiday and had a few more girls to see.”

He posted off an application to the Clan Line of Glasgow, a comfortable, regular passenger-cargo steamship service to India, and then kicked himself when the Clan’s job offer finally caught up with him in Rotterdam two weeks later, in what was to be the first of many thousands of dreary out-of-town Shell oil refinery berths. But he didn’t repine at taking Shell’s shilling. Or not much.

The wave of national rail and coal strikes that racked Britain that summer almost as soon as the celebration bunting came down would have prevented him joining the ship, or so he reasoned.

And by then he was also discovering some of the advantages of life in the growing Shell oil tanker fleet. “A man can make money here,” he wrote home.

The food and pay were good, he said, and he had a comfy bed and a Chinese “boy” to bring him tea in the mornings and clean his shoes. “It seems to me life is one continuous meal aboard here. In the last ship we used to get one meal a week.”

Monkbarns had been 267 feet long and 23 feet wide, with a very old Old Man, two very young mates, sixteen teenage apprentices and a barely competent crew of a dozen or less, depending on desertions. Shell’s oil-fired steamer Donax by comparison was 348ft long and 47ft wide (… “half the length of Guildford Road, and about as wide…”) with a young master, four ambitious mates, a chief engineer with five junior officers of his own, a Marconi wireless operator, and more than thirty Chinese firemen and crew.

Sea mines still menaced the shipping lanes in 1919. "When they float high out of the water, they are supposed to be 'dead'. Personally I have no desire to poke one of them to see," wrote Bert.

Life on Donax too was a world away from conditions aboard the old windjammer. Third officer Bert Sivell had his own clean, modern quarters with fitted cupboards, a writing desk and and armchair, electric lights and a fan, “and a dozen other things that one would never dream of in sail,” he wrote. The Chinese “boy” woke him at 7.30am each morning with hot buttered toast (“Real butter. Not margarine…”), and polished his boots until they shone like glass. Captain McDermuid was a jolly fellow, only 34 himself, who had welcomed his new juniors aboard with a bottle of wine. And the day the ship took on stores, Bert wrote in wonderment: “More stores have been sent to this vessel for a fortnight’s trip than would have arrived on the last one for a year.”

On top of the good pay, Shell offered a provident fund – 10% of salary, matched by 10% from the company plus a 15% annual bonus; three months holiday on half-pay every three years; and a £3 a month war bonus – because of the many sea mines still adrift undetected in the shipping lanes around Britain.

Above all, prospects for promotion were good. Anglo-Saxon Petroleum was expanding. Rapidly. In 1919 alone the company bought no fewer than 23 ships, to replace the eleven lost during the war. They were a mixed bag of former RN oilers built for the Admiralty and converted dry cargo carriers managed by the wartime Shipping Controller, but the company was agitating for permission from the National Maritime Board to raise its salaries by a further 40% (according to Bert’s new captain) to man them all.

It had been a snap decision to join Shell, but Bert never again left the booming oil giant, nor the girl – my grandmother – whom he had equally hastily met, wooed and won that August.

Read on: The girl next door

Previously: Oil tanker apprentice, 1919