Archive for the ‘Royal Mail steamers’ Category

A sailor’s life – 12. Coronation and seamen’s strike, 1911

Hammering and stitching on parade floats and fancy dress was in full swing up and down the British Isles, commemorative medals had been struck, and “meat teas” were being cooked up for the deserving poor. By the time Bertie Sivell, cabin boy, left Pernambuco in Brazil on 2 June 1911 bound for Southampton aboard the RMS Nile, the coronation of George V was barely three weeks away.

In the Solent, ships were gathering – hundreds of ships, private yachts and warships, cheek by jowl. Ticket sales for steamer trips round the assembled fleet were booming; from 1s 6d the week before the grand coronation fleet review, to a week’s pay – £1 10s – on the day. For an extra 6d, trippers could enjoy an hour aboard the visiting US battleship Delaware “by kind permission of the commander”.

No one expected the motley collection of nationalities crewing the ships to be able to unite in common cause for the seamen’s strike threatened on the 14th. No one expected a docks strike that would bring Britain to a juddering halt. But down in Southampton the trouble kicked off early, among the coal porters called to fuel the first of the White Star’s state-of-the-art new ocean liners for her maiden voyage.

Titanic was still under construction in Belfast, but her huge twin, Olympic, was bound for New York, booked solid to bring back half a hundred American millionaires for the coronation spectacle. If it seems an insane moment for the shipping companies to chance their arm with their workers, that’s because it was.

The coal porters were labourers, working in filthy black gangs of five men for up to twelve hours a day lifting mountains of coal into ships of all sizes for a penny halfpenny a ton. They had been called to standby the grand new Olympic at 6am the day after Nile left Brazil, but were kept waiting, unpaid, for five hours. When they were at last allowed to start work at 11am, they asked for a “monetary consideration” for the half day lost, suggesting five shillings each. When it was summarily refused, the men downed tools.

By mid afternoon, the colliery firm had realised its mistake and revised its response, offering first three shillings, then four, and eventually the full five. But by then the coal porters had thought of other grievances and conditions, and more men were joining them. By Tuesday, the strike was declared official and a union organiser arrived from London – together with the first contingent of blackleg labour.

Harry Orbell had 28 years’ experience of industrial disputes. He opened the meeting by thanking the authorities for letting the men meet behind the Seamen’s Mission, and he called for calm – no rowdyism, no causing trouble in town, he said, and he urged the strikers to remember that “whatever happened” the police were only carrying out the laws made by representatives of the people themselves. He didn’t blame the heads of the colliery firm, Russell Rea and his son, whom he said he knew personally and had always found to act as gentlemen (“hear, hear” roared a voice from the crowd). No, he said, the fault lay with the whippersnappers who got their pay rises by “winking at the boss’s daughter”.

The demands Orbell eventually laid before Rea & Co were for an extra halfpenny a ton per man, plus 7s 6d to work through the night, 6 shillings for working Sunday mornings, (4s for Sunday afternoons), and reasonable notice for overtime. Union recognition was almost an afterthought, but the firm still said no.

By Thursday the strike had spread to the steamers and yachts gathering in Southampton Water to run coronation cruises, after their owners too refused to pay the higher coaling rates. The striking coal porters waived their own picket lines for two vessels: one of which had put into port in distress and on fire, and the other “so as not to inconvenience the general public” as it contained only household coal, the Southampton Times & Hampshire Express reported. Reports of the strike were well back in the paper, on page 10.

But time was running out for the liner companies. Seamen on the US liner St Paul were offered $750 dollars to coal the ship themselves, even the ship’s stewards were approached, but they all refused. In New York there were railway presidents and bankers waiting to be picked up. All the £800 state rooms for the return passage were booked. Olympic’s maiden voyage – carrying the directors of both the White Star line and the ship builders Harland & Wolff – looked doomed. (Both they and Olympic’s commander, Captain Edward Smith, should have taken note. All three sailed on Titanic’s maiden voyage the following year. Only one survived.)

So, White Star capitulated. And then the seamen seized their chance, “heartened,” as the local paper reported, by the coal porters’ success. On the morning of the day the international seamen’s strike was to be declared, Olympic’s crew struck, demanding parity of pay with the rival Mauretania – and the White Star directors settled again, allowing Olympic to finally steam out of Southampton at noon on June 14th, leaving seething industrial unrest in her wake. The New York Times reported: “Strike of seamen ordered for to-day. Has already begun at Antwerp. English owners appear unconcerned.” Men refusing to board their vessels in the US would be deported and jailed, it said.

By evening the unionist leader Tom Mann in Liverpool had “declared war” on the shipping companies for £5 10s a month minimum wage and union recognition, but not before the Liverpool organisers had issued a message dismissing the strike in Southampton as premature. “This probably explains why some of the London papers did not awake to the fact that there was a strike until Thursday morning,” wrote the Southampton Times, sniffily. Premature or not, a week before the coronation thousands of seafarers in all the large ports had responded, and the strike had spread to the shore gangs. Atlantic sailings were cancelled, and even the cross-Channel service was threatened.

As ship after ship arrived in port, more seamen joined the strike. The stewardesses on the Union Castle liner Briton joined, the ship’s bandsmen followed, and on shore even ships’ printers were agitating for more pay. In the commotion, the Union Castle laundry girls – who worked nine hours a day for a pittance of 6s a week – approached their manageress for news of their own outstanding claim. When she rather rashly responded that the officials were far too busy to consider “such a matter as that”, they too walked out, leaving the linen for several thousand bunks unwashed.

It rained in Southampton on the day of King George’s coronation, a steady drizzle. As wet processions trailed through the town, the negotiations continued.

Having bowed to force majeure twice, White Star had jibbed and withdrawn its liner Majestic from the coronation pageant, ceding her place to St Paul, whose crew, because signed in the US and therefore not yet discharged, could be compelled to sail. Majestic had been laid-up in the river, where she was now joined by other laid-up liners as scheduled sailings began to be cancelled and cargoes diverted. Four days before the Coronation, the frantic managers of the Royal Mail and Union Castle made it known that they were offering “liberal terms” to anyone willing to crew the ships in the review that Saturday, but the seamen refused, pointing out that it was more important to be adequately paid for all the other days of the year.

The talking continued right up to the afternoon before the review, and White Star was the last to settle. At ten past two on Saturday 24th June 1911, the Southampton seamen’s strike was over: the shipping companies having agreed to a pay rise of 10s a month for deck hands and men in the stoke hold, and the shore gangs all getting an extra 1s 6d a week.

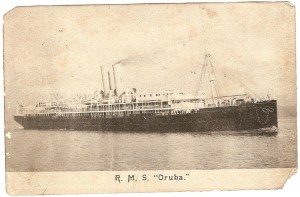

Olympic arrived back packed to the railings with millionaires. Forty or fifty of them, with an “aggregate wealth of £60m!” reported the Southampton Times. But it was too late for the Royal Mail, which had had to pull four fully-booked ships out of the royal parade, including Asturias and little Oruba. Four Union Castle ships had also been pulled, including the Armadale Castle.

Bertie Sivell arrived back in England that evening, just in time for the illuminations. Four days later he was laid off, when a national docks strike was called, crippling trade through every port up and down the country. Nile’s next sailing was cancelled, so on June 28 1911 Bertie went home to his mam and dad on the Isle of Wight.

By August he was apprenticed – in sail.

Read on: A sailor’s life – 13. Apprenticeship

Previously: For the record, finding ships’ logs

A sailor’s life – 10. Below decks: RMS Nile, 1911

Several ship’s logs for the Royal Mail steamers Nile and Oruba for 1911 survive in the Public Record Office at Kew. Though no more than a basic note by busy officers, they provide a rather blunter take on life at sea than the pictures of leisure and pleasure painted by the passengers and the shipping company guides.

Injuries figure large, particularly the burns, which were an occupational hazard among the stokers sweating in the bowels of the steam packets, endlessly shovelling coal into the furnaces; above decks, winches and other machinery took their toll of extremities. On one crossing Oruba’s master recorded, beside the usual desertions on the South America run, five crew laid up with various fractures, tonsillitis and rheumatic fever.

Both steamers either had to put sailors ashore for medical treatment, or had them put aboard by the consul for repatriation to the UK. Ordinary merchant ships did not carry a doctor, just the captain with a St John Ambulance certificate and a copy of the Ship Captain’s Medical Guide. If a man became too ill to be treated aboard, the ship put him ashore as soon as it could – and sailed on. Time and tide wait for no man. Money owed for the days worked was left for him, but his pay stopped until he went back to sea again. When the money ran out, he became a job for the local consul. Such men had their own shorthand presence in the logs: DBS, for distressed British seaman.

The voyage marked by the death of Nellie Thompson, Countess of Shannon, saw eight DBSs put on board Nile by various consuls for conveyance back to Southampton. Between them, they had typhoid, small pox, tuberculosis, chronic bronchitis, neuralgia, and severe burns in various limbs. The passenger ship doctor who had treated the countess’ pneumonia with “poultices, milk diet, digitalis, strychnine, sponging etc” recorded of the working men only that he had put the typhoid and the small pox cases on “saloon fare” and dosed the bronchitis and the TB with cod liver oil.

For this, the logs record an experienced seaman on Nile earned £4 a month, and a coal trimmer, (which was the nastiest job in the engine department) £3 15s. The waiters, rushing between decks with four meals a day for 600 passengers, supported themselves and their families ashore on £2 10s a month. Even the first officer – who would have studied at his own expense for years, coming ashore to sit each ‘ticket’- received only £16 a month.

Amid the comforts of the passenger liners, the discrepancy between the haves in saloon and those who laboured below and around them was sharp. The Manchester Guardian that year noted: “… on the average, seamen and firemen [stokers] are worse paid, worse lodged and probably, even to-day, worse fed than Englishmen doing comparable work ashore.”

Shipboard discipline, at the sole discretion of the master, added to the financial squeeze. Crispino dos Santos, a 3rd class waiter on Nile, was fined 5s* for quarrelling with the passengers — which was nearly three days’ pay to his family. The bosun’s mate and a firemen were fined 5s each for being drunk off duty, and the fireman subsequently lost a further day’s pay for “insolence” to the 3rd Engineer. Even the 3rd Mate was fined, for calling the 2nd Mate “a damned liar”.

“It is not that shipowners are an exceptionally rapacious class of employers,” wrote the Guardian, “but that the seafaring trades are cosmopolitan … Apart from the great passenger steamers, which run between the same ports with the regularity of express trains, the world’s shipping trade is carried on by vessels ready to go anywhere, carry anything, and employ anyone, irrespective of race, who is able to fire a marine boiler or do a seaman’s work, and it inevitably follows that the standard of pay and comfort for the crews tends to fall to that of the world’s labour market rather than rise to that of prosperous countries like England and the United States.”

At the end of May 1911, the Southampton Times carried a report from the Lancet on the “crowded, damp, dark and dirty” living conditions on Britain’s merchant ships and the “crying need of sailors” for ventilation and proper washing facilities. Special interest attached to this, the newspaper explained, in view of the mounting industrial tension among seamen.

*(20 shillings to the £)

A sailor’s life – 9. Crossing the Line

“All the traditional ceremonies and good-natured horseplay were scrupulously adhered to, and some twenty schoolboys and five adults were duly dosed, lathered, shaved, hosed and then toppled backwards into a huge canvas tank of sea-waters,” wrote young Lord Frederic Spencer Hamilton, homeward bound from Cape Town aboard a Royal Mail Steam packet ship in 1910.

For hundreds of years sailors have marked a boy’s first crossing of “the Line” between the northern and southern oceans with a ritual ducking in the sea. Rope would be frayed for wigs, and lockers and stores raided for robes and crown. Then Neptune and his queen, a dame with large loose bosoms and ill-concealed stubble dabbed in flour, would appear over the side of the ship in mid ocean and advance on any so called “first trippers” to lather, dose and dunk them. At the end of their baptism, the new boys were presented with the right to sail the seven seas, and could look forward to being on the delivering end of the brutalities next trip.

Crossing the line ... cruise ship passengers anno 2009, still paying their respects to Neptune in style, from Johnhealds.blog

The tradition had flourished on passenger ships, because it broke the monotony of long idle days for strangers bored with each other and themselves and writing letters. The ghastly Lord Fred was obviously a hoot, recording riotous goings-on apparently initiated by choice spirits among the saloon crowd, with him playing Neptune “in an airy costume of fish-scales”. A star of the South African music hall had played the queen, he wrote, with a flow of risqué gags that had their audience in stitches.

“Just as we crossed the Line, the ship was hailed from the sea, her name and destination were ascertained, and she was peremptorily ordered to heave to, Neptune naturally imagining that he was still dealing with sailing ships. The engines were at once stopped, and Neptune, with his Queen, his Doctor, his Barber, his Sea Bears and the rest of his Court, all in their traditional get-up, made their appearance on the upper deck, to the abject terror of some of the little children, who howled dismally.

“The proceedings were terminated by Neptune and his entire Court following the neophytes into the tank, and I am afraid that we induced some half-dozen male spectators to accompany us into the tank rather against their will, one old German absolutely fuming with rage at the unprecedented liberty that was being taken with him.”

Read on: Below decks: RMS Nile, 1911

Previously: Rolling down to Rio

From: Here, There and Everywhere by Lord Frederic Hamilton

A sailor’s life – 8. Rolling down to Rio: RMS Nile, 1911

I’ve never sailed the Amazon,

I’ve never reached Brazil;

But the Don and Magdalena,

they can go there when they will!

Yes, weekly from Southampton,

great steamers, white and gold,

Go rolling down to Rio

(Roll down, roll down to Rio)

And I’d like to roll to Rio

some day before I’m old

From The Beginning of the Armadillos, Just So Stories, 1902

Five months after running off to sea with the Royal Mail steam packets from Southampton, Bertie Sivell, still only fifteen years old, changed ships and at last rolled down to Rio as Rudyard Kipling had described, crossing the equator en route.

The RMS Nile had been purpose-built for the Argentine run with four promenade decks and nearly as many passengers in saloon class as in steerage. She shuttled from Southampton to Buenos Aires and back every eight weeks, crossing the Atlantic from St Vincent in the Cape Verde islands to Pernambuco (now Recife) in Brazil, and calling at Lisbon, Bahia (now Salvador), Rio de Janeiro and Montevideo.

The RMSP’s hefty Guide to Brazil and the River Plate for the year 1904 reports of St Vincent that it was very healthy, due to stringent quarantine regulations, but that there was not much to do ashore except take amusing photographs “of the coloured people and their numerous children”. Pernambuco, too, was picturesque, (“especially to the traveller who has not seen tropical scenery before”), and it benefited from restaurants and even a music hall. Although “to the lady of fashion neither the drapers nor the milliners establishments would form much attraction”, the guide warned. Somewhere between the two Bertie crossed the Line.

He sent six picture postcards from Lisbon, all blank, and twelve from St Vincent, showing the harbour, the market and a view of naked children around a mud hut, inscribed “this shows the general mode of living in these islands”. One marked where the ship lay in the bay, and one a church he could either see from the moorings or had visited. But nothing was found from Pernambuco.

In Rio, where the Sugar Loaf mountain loomed over picturesque forts, the ship threaded its way through a mass of shipping and Brazilian men-of-war to anchor off an island opposite the city. There, “fussy steam launches blowing their whistles” would race up, bringing family and friends too impatient to wait on shore, the guide said. The guide did not say that in Rio and Buenos Aires desertions among the crew were rife because both had rip-roaring sailor towns full of cheap booze and whores, and a nasty reputation for crimping or press-ganging, which remained widespread until the First World War. In Buenos Aires Bert bought coloured cards, but again did not write on them.

If Bert ever told the son he hardly knew what had happened to him that first trip across the Line, the boy did not remember it and if the teenager on Nile wrote letters, they were not kept.

The only record is Nile’s log, which shows that three days out of Southampton, Bertie Sivell, one of two page boys on board, was promoted to Captain’s Servant at £1 per month, backdated. Logs were only preserved if they recorded a death or illness, discipline problems or, more rarely, a marriage or birth. Nile’s log for 1911 survived because several men, including the “Jews’ waiter”, deserted the ship in Buenos Aires.