Posts Tagged ‘Captain James Donaldson’

A sailor’s life – 36. Monkbarns, Rio 1918

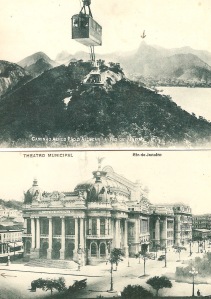

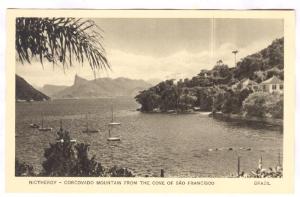

Bert Sivell marked his seventh anniversary aboard the sailing ship Monkbarns in Rio, with a big cigar and a trip up the Corcovado mountain — three years before building began on the 130ft figure of Christ the Redeemer. It was August 1918 and a postcard view marks the empty summit with an arrow.

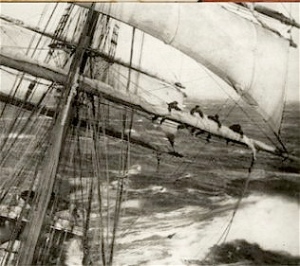

He had been to church, he wrote to his father (as you do), and was developing quite a taste for the cheap local cigars, of which he was laying in a stock. Monkbarns was in dry dock across the bay in Nictheroy, undergoing repairs, a big grey rust-streaked hull dwarfed by her three tall masts – the main being 192ft from truck to keelson. She could set twenty-three sails, and needed twenty-four hands to work her. “Who would have thought when I joined her that I would be mate before being six years at sea,” Bert wrote. He was 23.

Rio harbour during the first world war was a magnificent sheet of water ringed with jungle-clad peaks and big city sprawl, and dotted with palm islands. There were ships of every sort, from cruisers and destroyers to Atlantic liners and little steam coasters, and between them all tall sailing ships, barques, brigs and schooners, loading or unloading cargoes, and bobbing at the farewell buoys.

Captain James Donaldson, his young officers and the four remaining apprentices had been left kicking their heels in Rio for two months since Monkbarns’ mutinous crew were convicted at a trial on HMS Armadale Castle that June, and they were to remain for one more month while the boys’ half-deck house was enlarged. The cargo of flour had been whisked north by a Lamport and Holt steamship and John Stewart & Co were sending out ten new little apprentice boys to work the ship home. Never again would Monkbarns’ fo’c’sle hands outnumber the officers.

Next: John Stewart & Co’s new apprentices

Previous: Crimes and punishment

Written by Jay Sivell

July 26, 2010 at 9:06 am

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Historical postcards, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship mutiny, WWI

Tagged with apprentice, Bert Sivell, Captain James Donaldson, discipline and desertions, handelsmarine, John Stewart & Co, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, marina mercante, marine marchande, merchant navy, Mutiny, Rio de Janeiro 1918, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, square rigger, war at sea, windjammer

A sailor’s life – 35. Monkbarns: crimes and punishment

What ordinary seaman Fausto Humberto Villaverde thought of his trial aboard the HMS Armadale Castle in June 1918 was not clear. Charged with “combining to disobey lawful commands” – or mutiny, as his officers saw it, the evidence had to be translated into Spanish for him, and even the translator appeared to have struggled with his replies. The Peruvian’s defence is given as one line: he had “illness in the stomach”.

The Dane Soren Sorensen had been heard first. Unlike the other men, he was accused only of insubordination – for having answered back when Monkbarns’ master, Captain James Donaldson, criticised his steering. He denied using bad language. He claimed the master had sarcastically asked what time he, Sorensen, would be able to steer the ship and that when he had complained he was feeling sick Donaldson had threatened to “smash him in the face”. The only witness on the poop at the time was the young 2nd Mate, Aplin, who did not support this version of events.

As Sorensen had technically already been punished, by the imposition of the five shilling fines – which was all the authority Donaldson had under British maritime law – he was found guilty but no further action was taken.

The Irishman Thomas O’Brien was called next by the impromptu naval court in Rio bay and was asked to explain his refusal to grease down a mast when ordered to do so. His defence that he was starving met short shrift from both British ship captains officiating. “You don’t look like a man that had been starved,” they said.

They wanted to know why, if the food was so bad, O’Brien had bothered to steal more of it during the voyage from Melbourne, as he admitted. He claimed he had only disobeyed orders because he was “played out from starvation” and too weak to work, “except where it was necessary”. But his judges jumped on the rider.

Was he to be the judge of that, asked the president. “Suppose you were ordered aloft to furl a royal [sail], am I to understand that you wouldn’t go unless you thought it necessary? Who is the best judge of what is necessary, you or your properly appointed officers?”

When the American, Charles Moore, also complained about the food, and particularly the substitution of grease for butter the president exclaimed “Butter! Do you expect to get butter in wartime. Margarine is considered a luxury in London.”

The Welshman David Thomas’ evidence is the most poignant. “I thought I was going home,” he told the hearing. Perhaps Captain Donaldson – desperate to replace deserters in Australia – had been a little economical with the truth. By the time the ship left Melbourne their cargo of flour was destined for New York, not wartorn Europe.

At 45, Thomas was the oldest man in the fo’c’sle, and he had suffered rheumatism and cramps from sleeping in a wet bunk during the long, stormy passage round the Horn. Though only rated able seaman on Monkbarns, he had done two voyages as bo’sun on his previous ship, he said, which showed he was not of such bad character as painted. He had not been looking for “any bother”. He had gone aloft when he could. His handwriting in the crew list is shaky like an old man’s and there is no year against his last ship.

He was scathing on the subject of the pantry however. The food was so bad it made him sick, he said, and he had seen some of the boys in the ship so hungry they would get a cup of flour and fry it in fat in the galley to have something to eat.

The mate (Bert Sivell) half stuck up for him, telling the court that Thomas would usually go aloft to make sail fast, although he had refused to do so for the greasing, but the president wasn’t having any of it. “Well, if he can go aloft to take in sails he can go aloft to grease down the mast,” he said, firmly.

Thomas and O’Brien were found guilty of continued wilful disobedience. Moore, Henriksen and Villaverde were found guilty of combining to disobey.

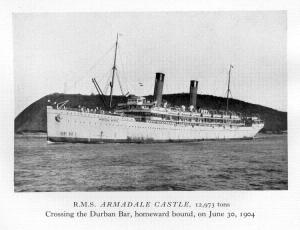

All five men were sentenced to twelve weeks in prison in the UK and the cost of their “board” on the passage home, which was calculated at three shillings a day for 38 days. Thomas and O’Brien were also fined six days pay, and O’Brien was further charged £2 for the food he had admitted stealing. They set off in convoy under lock and key aboard the Armadale Castle in July and arrived in Newport, Wales, after an uneventful crossing on August 4th.

Sub-lieutenant George Frost’s last sight of them was handcuffed together on the railway platform at Newport, waiting for a train to take them to prison. They had six weeks of their sentence left to serve. For them, the war was over.

Read on: John Stewart & Co sends out new apprentices

Previous: The court martial

Written by Jay Sivell

July 25, 2010 at 4:19 pm

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship mutiny, WWI

Tagged with apprentice, Armadale Castle, Captain James Donaldson, discipline and desertions, Fausto Humberto Villaverde, handelsmarine, John Stewart & Co, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, marina mercante, marine marchande, merchant navy, Mutiny, Rio de Janeiro 1918, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, Soren Sorensen, square rigger, war at sea, windjammer

A sailor’s life – 34. Monkbarns, court martial 1918

On the 28th June 1918, a British naval court was convened in Rio bay to try six predominantly foreign seamen for “wilful disobedience to lawful commands” on a British ship – Monkbarns. It passed into history as a mutiny, but was it?

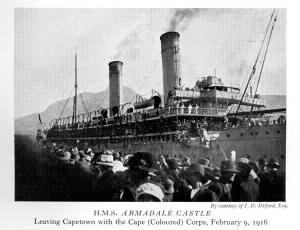

The hearing was held on the HMS Armadale Castle, an armed merchant cruiser/former passenger liner, and was presided over by her commander, Captain George Leith RN, her chief officer, Lieutenant William Pawlett Evans RNR, and Captain Robert Smith, master of the British steam ship Messenia, which just happened to be in port.

Monkbarns had sailed desperately into the busy tangle of steamers in Rio bay four days previously flying distress flags and seeking protection from mutineers in her fo’c’sle, and under the quite astonishingly wide-ranging powers of the Merchant Shipping Act 1894, section 480 (only repealed in 1994!), this was deemed sufficient to bypass Brazilian jurisdiction.

Captain Leith’s log does not record what Captain James Donaldson was signalling as he came, but whatever it was, Armadale Castle instantly dispatched a dozen armed men out to Monkbarns in a boarding party commanded by sub-lieutenant George Merry Frost, RNR.

Frost knew Monkbarns, having visited her in the Thames at Greenhithe when he was a boy on the nautical training ship Worcester. Now, as he boarded the ship in distress, in wartime, on the other side of the world, he spotted a familiar face – another HMS Worcester boy, Monkbarns 2nd Mate Bill Aplin – and was borne aft to the saloon to hear the officers’ tale.

The crew had forced the ship into port by refusing to work her, in protest at the food aboard. The mate’s log referred to it as mutiny, but until then it was the officers’ word against theirs. A hot headed young American seaman and an inarticulate Peruvian were about to change that.

Corporal Thomas Perkins of the Royal Marine Light Infantry, posted on guard aboard overnight, became the first witness for the prosecution the following morning when three of the crew – Charles Moore, Fausto Humberto Villaverde and the Norwegian cook, Edvard Henriksen – refused to “turn to”, at the start of their watch.

The men claimed they were ill, but when a doctor (second witness) arrived from shore and certified them fit to work they refused again. Moore, 21, and Villaverde, 22, packed their bags and appeared on deck smoking, the subsequent trial was told. So Frost arrested them. They had been warned, he said. Though possibly they underestimated the long arm of British justice.

Edvard Henriksen, also 22, meanwhile had been found asleep in his bunk. When roused and challenged with refusing to get up for work, the Norwegian offered the first excuse that came into his fuddled head: toothache, he said. This proved a bad move, as he was marched off up on deck and the tooth he randomly identified was yanked out on the spot over the main hatch – without anaesthetic. Henriksen too was then ordered back to work and when he refused was also arrested.

Frost told the court later they had all refused to serve further on Monkbarns, “though they said would on another vessel”.

In all, six men finally appeared before court on the Armadale Castle: Moore, Villaverde, Henriksen, an elderly Welshman called David Thomas, an Irishman, Thomas O’Brien and a Dane, Soren Sorensen. Only Henriksen pleaded guilty.

Read on: Crimes and punishment

Previously: Monkbarns, mutiny III

Written by Jay Sivell

July 19, 2010 at 11:22 am

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Historical postcards, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, WWI

Tagged with AMC Armadale Castle, apprentice, Captain James Donaldson, discipline and desertions, George Merry Frost RNR, handelsmarine, John Stewart & Co, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, marina mercante, marine marchande, merchant navy, Mutiny, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, square rigger, war at sea, windjammer

A sailor’s life – 33. Monkbarns, mutiny III

“The crew are in a state of mutiny and insubordination whenever there is any work to be done, whether handling sails or braces,” wrote Bert Sivell, the young mate of the sailing ship Monkbarns, in June 1918, as they finally rounded the icy southern tip of South America back into the Atlantic after nearly three months trying.

Two days after the ship turned north, the 2nd mate’s locker was broken into and ropes and gear inside were taken or destroyed. Three men, the Irishman Thomas O’Brien, the Welshman David Thomas and the Dutchman A. van Eijk, reported sick. When the mate went to see them in the fo’c’sle, they “complained of weakness through starvation and lack of good food”. Bert wrote: “The master, using patience and humanity in dealing with the crew, and not wishing to have bloodshed in the ship, refrains from entering the offences in the Official Log Book, because that would be the beginning of very serious trouble.”

On June 12th the metal reflectors were stolen from the sidelights, and only one was found. “There is undoubtedly foul play going on in the ship,” wrote Bert.

On the 14th Fausto Humberto Villaverde, the Peruvian, carrying a breakfast of fish aft to the watch on the poop deck, tipped it deliberately overboard instead. “As far as could be seen the fish was clean and well cooked,” reported Bert, whose breakfast it had been.

The crisis came on the 15th, when the very youngest of the four mates — Ted Chown, six days out of his apprenticeship — began the morning watch by handing Villaverde a grease pot and ordering him to climb up and grease down the foremast and the iron collars of the yards.

It was necessary for the smooth running of the sails, but it was by custom and practice a boy’s job. Villaverde refused, and he refused again when the acting 2nd mate went forward to try his authority. The rest of the starboard watch, listening in from the shelter of the forecastle head, also refused. Bert arrived after breakfast at 8.30am and handed the job onto O’Brien, who was by then on watch instead, but the Irishman said he was too sick. The Welshman said he was sick too, and the rest of the port watch followed. Even the previously loyal young seaman Laurence O’Keeffe, who had been with the ship since Cardiff, dared not break rank.

At that, the court was later told, the mate “considering the job important” went aloft himself. Bert greased down the mainmast, Aplin did the foremast, and Cheetham did the mizzen mast when he came back on duty for the afternoon watch.

Donaldson gave up. After a council of war in the saloon, the beleaguered officers decided to seek refuge in a friendly port. Witnessed by Donaldson, Bert and Aplin, the official log records: “Since shortly after leaving Melbourne the seamen have been in a state of insubordination and insolent defiance or mutinous. Now they, the seamen, have combined to disobey orders and refuse to perform duties except what they choose. Therefore the Master and Officers are doing their utmost to make a port safely in distress with what assistance the seamen will give them.”

Bert’s comments were appended. “The mate had heard a rumour when the ship was a good way west of the Horn, to the effect that as soon as she was round the Horn, the crew were going to refuse to do any work except haul on the braces and wash decks. The master and officers were consequently prepared for this happening,” he wrote.

“The master and officers are waiting with patience and watching carefully the turn of events, hoping that it will smoulder down and die a natural death.”

They set course for Rio de Janeiro and for four days the young mates worked the sails alone. “There is not the slightest confidence to be put in the men,” wrote Bert. “If there is any work to do they are sick.” Food continued to be stolen from the galley, but Edvard Henriksen the Norwegian cook was “apparently unable to throw any light on the matter”.

Within sight of Rio’s Sugar Loaf mountain, however, the steady wind that had wafted them towards land dropped. No tug came out in response to their signals; so – fearful of what might happen if he did, but more fearful of the consequences if he didn’t – Donaldson recklessly steered the old sailing ship straight into the teeming bay, through the middle of a departing convoy, and slap into the arms of HMS Armadale Castle, an armed merchant cruiser awaiting the next convoy out.

Read on: Summary justice on the Armadale Castle, Rio 1918

Previously: Monkbarns, mutiny II

Written by Jay Sivell

July 13, 2010 at 10:54 am

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, WWI

Tagged with apprentice, Captain James Donaldson, discipline and desertions, handelsmarine, John Stewart & Co, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, marina mercante, marine marchande, merchant navy, Mutiny, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, war at sea, windjammer

A sailor’s life – 32. Monkbarns, mutiny II

The Old Man was too old and the mates were too young, the ringleaders of the Monkbarns mutiny told the naval court in Rio in June 1918. The old windjammer had sailed from Melbourne in March, bound for New York with flour for the US army, but within a week the new hands decided they did not like the food. The world was at war, but they wanted butter.

“There have been days I couldn’t eat anything,” the Welshman David Thomas protested later, when he was charged with refusing lawful commands to work. “I complained the first day I saw their stores. I don’t know whether they have been cleaned, but the Pantry, the Lazarette and the Galley are well worth seeing. The conditions of the food made me sick.”

Captain James Donaldson was 69 in March 1918, though the men believed him 76 – and all four of his very young mates were his own former apprentices. The chief officer, only 22 and bursting with pride at his new stripes, was Bert Sivell.

Two grinding months later they were still west of Cape Horn, wrestling with sails and high seas – and mutiny.

The sea soaked bunks never got a chance to dry, and down in the fo’c’sle the eight new men signed in Australia knew their rights. The food was bad, and running out, they said. They demanded to put into port. Donaldson tried reasoning. The food was not the very best, he agreed, but it was difficult provisioning sailing ships in wartime. What they had aboard was sustaining, he said. The “bear’s grease” was indeed not butter but it was margarine, and despite the unusually slow passage they were making there was enough of everything to last to New York. He refused to change course.

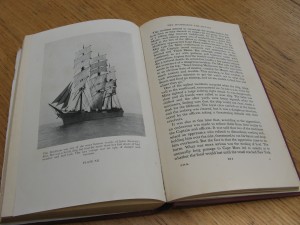

"Threatened to cut his throat and drop him overboard". From The Wheel's Kick and the Wind's Song, AG Course (1950)

The men retaliated by refusing to work. Pressure mounted on the four remaining apprentices to join the boycott (see right). Apart from the boys and the elderly sailmaker and carpenter there was only a single young ordinary seaman, Laurence O’Keeffe, to work the ship.

By May 19th the weather had improved but it took 17 minutes to get the watch out on duty, Bert recorded. “Since leaving Melbourne the crew have been in an obvious state of mutiny,” he wrote, “causing the Master and officers much anxiety.” With the prospect of mountainous seas, ice and gale force winds around the Horn, the safety of the ship was at risk. The barometer fell and fell.

Under cover of darkness, in the middle watches, dwindling stores began to disappear faster. A tin here, a mouthful there, but Edvard Henriksen the cook knew nothing.

On the 30th the Irishman Thomas O’Brien was spotted at midnight stealing pork from the cask aft. The young 3rd mate, Gilbert Cheetham, who witnessed the theft, did not intervene, a forebearance justified in the certified extracts of the mate’s log as having been due to young Cheetham’s “wishing to find whether this kind of thing was a practice”.

Captain G.R. Cheetham of the Blue Funnel Line later claimed he had in fact made the felon put the meat back. “He remembers the incident clearly,” wrote AG Course, a fellow John Stewart & Co apprentice, chronicling the last days of what would be the last British-registered sailing ship line.

Donaldson had issued the younger mates with revolvers and three rounds of ammunition. Although Bert had been officially standing in as mate since the ship left Newport News, Virginia, twelve months previously, William Aplin the acting 2nd had graduated from the half deck only eight months previously and Cheetham and Chown were in fact still apprentices. When their time expired in June, they were entered on the ship’s papers as acting 3rd and 4th, but by then the ship had rounded the Horn and was heading north again into steadier winds.

Keeping order at sea was not easy at the best of times. Outnumbered, far from land and responsible for all the lives and cargo aboard but with no means of preserving discipline other than force of personality, masters needed to command the crew’s respect — and they needed tough officers to enforce unwelcome decisions. Mates had to be handy with their fists. There were abuses.

(“Nowadays,” wrote Basil Lubbock, “some crews are composed of such villainous scoundrels that unless you take a high hand with them, and show them you are not to be trifled with, they would soon take advantage of what they would call a softy and a reign of terror would begin. Any sort of discipline would be impossible, the men would do just as much work as they felt inclined for, and they would openly sneer and scoff at you if ordered to do anything they did not wish.”)

When an iceberg suddenly reared up dead ahead of Monkbarns at 2am one night as they battled blind round Tierra del Fuego, all hands had turned out at the mate’s bellow and every muscle had strained to pull the yards round, to avert collision. Terror spurred them all. But as the ice mountain closed, and they heard in their minds the sound of the jagged skirts of ice beneath and round them beginning to scrape, nerve broke. A group of men abandoned their hauling and ran for the lifeboats, believing the ship lost, and the officers pulled their guns. Or so Course said.

Oddly, the incident recalled so vividly and convivially in the former apprentices’ later barside chats (and reproduced in his book) was not among the accusations raised at the naval hearing aboard the armed merchant cruiser Armadale Castle in Rio in 1918.

The certified extracts of the log produced in Rio and held at the Public Record Office in Kew record only that on the morning of June 5th, with land in sight north-east of the Horn, the officers hoisted the international distress flags NC under the red ensign.

All cooperation from the fo’c’sle had ceased. But no help came out from shore.

Read on: Monkbarns, mutiny III

Previously: Monkbarns, mutiny I

Work in progress: the book I never wrote about the sailor grandfather I never knew, from his apprenticeship on the square-rigger Monkbarns to his death by U97, presumed lost with all hands aboard the Shell oil tanker Chama in 1941 Blogroll

Written by Jay Sivell

July 12, 2010 at 12:01 pm

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, WWI

Tagged with apprentice, Captain James Donaldson, discipline and desertions, handelsmarine, John Stewart & Co, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, marina mercante, marine marchande, merchant navy, Mutiny, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, square rigger, war at sea, windjammer

A sailor’s life – 31. Monkbarns, mutiny I

Meals were eaten in silence on Monkbarns towards the end, the little mate chewing grimly with a revolver at his side and the even grimmer Old Man ramrod straight at the head of the table. The old windjammer creaked and moaned around them and the oil lamp swung crazily overhead while the junior officers scraped their spoons, keen to escape back to the wind and the sails. They spoke when spoken to, which was seldom.

Insubordination had begun before the crew even left Melbourne. The last eight men signed on were all older than the other hands, and outnumbered them. And when Monkbarns sailed on March 20th 1918 facing a winter passage round the Horn, they knew their rights.

Within a week, bad weather compounded the ship’s troubles. Huge waves swept the decks, swamping the bunks in the fo’c’sle and extinguishing the galley fire so the men could have neither cooked meals nor hot drinks. Ten days out, they were still beating across the Tasman Sea.

When Captain Donaldson snapped sarcastically at Soren Theodor Sorensen for poor steering one day as he struggled to brace his sextant to take the noon sight, the Dane did the unthinkable and answered back. The offence was logged, but as word got back to the multinational crowd in the fo’c’sle that the only sanction available to Donaldson under British maritime law was a derisory five shilling fine, respect for the saloon nose-dived.

Only drunkenness merited a 10 shilling fine, and then only for a second offence. For all other infractions the ship’s papers stipulated a penalty of five shillings, unless “otherwise dealt with” by law.

When the order next came to replace sails destroyed in the gale, the crew did not rush.

Day struggled into day with the winds wailing around them and no land in sight. Weeks became months, and the rough meals got rougher as levels in the casks and bins fell. In the mugs, the black liquid they called coffee quivered under the waves’ pounding.

Down among the sodden bunks, the men began to mutter. The potatoes were black and uneatable, they said, and the peas were so hard it took a mallet to split them. They had no soft bread, and only flour and molasses in the place of porridge, while instead of butter they had margarine bought in Buenos Aires six months previously, which they spurned as “bear’s grease”.

Eventually a deputation headed by the Irishman, Thomas O’Brien, went aft.

What happened next is not beyond dispute. Captain Alfred George Course, the first editor of the British Cape Horner magazine, never sailed on Monkbarns, but he spent a lot of time in bars with men who did, recording their tales (and writing them up under the pen name Leigh Forebrace. His little joke.) Course wrote that Captain Donaldson’s mutinous crew invaded the poop during the second dog watch that May, threw the Old Man over his chart table and threatened to cut him to pieces, but – like several of the other lurid accounts he recorded – this was not produced in evidence at the naval court hearing that was held in Rio three months later.

Certainly, the despised “bear’s grease” was taken aft and thrown at the feet of the master, but the men claimed Donaldson had stayed in his chart room and sent the 1st mate out with promises of more food.

The mate did testify that after May 15th he took to carrying a loaded revolver around with him in his pocket whenever he went on deck, day or night. He was just turned 23, newly promoted and at 5ft 2ins a good head shorter than every other man and boy aboard.

The mate in question was, by then, young Bertie Sivell.

Poor Bert, it was to be a baptism of fire.

Read on: Monkbarns, mutiny II

Previously: For those in peril

Written by Jay Sivell

July 6, 2010 at 1:20 pm

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, WWI

Tagged with apprentice, Captain James Donaldson, discipline and desertions, handelsmarine, John Stewart & Co, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, marina mercante, marine marchande, merchant navy, Mutiny, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, square rigger, war at sea, windjammer

A sailor’s life – 30. For those in peril

For merchant seamen, war at sea is never just enemy submarines, mine fields and warships; all the everyday hazards of wind, sea, dangerous cargoes, injury and isolation do not go away because a couple of countries far away are at loggerheads.

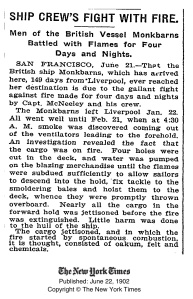

In May 1917, the sailing ship Monkbarns – bearing an unfortunate resemblance to a disguised German raider newly reported at large in the southern Atlantic – left Montevideo in Uruguay bound for Newport News, Virginia, and on arrival in the US lost eleven men, including every single one of the hands picked up in South America to replace deserters there. They were left kicking their heels in Newport for weeks while Captain Donaldson struggled to find crew, and out at sea the shipping losses mounted.

America had finally abandoned neutrality that April, and so it was the battleship USS South Carolina that sighted the supposed enemy raider See-Adler early on September 18th en route for Buenos Aires and ordered her at gunpoint to heave to. At breakfast time that morning, Monkbarns found herself being boarded and searched by the US navy, under one Ensign J. Wilkes.

Sadly, Bert Sivell’s surviving postcards make no mention of See-Adler or the US naval patrol, but he does comment dourly on the quality of American coal and the stevedores who stowed it wet. The cargo picked up in Newport News heated badly, he wrote, and they narrowly avoided having to put back into Montevideo with the ship on fire. Fire in the hold or a cargo that shifted, capsizing the ship, were the stuff of nightmares.

Newport had been all heat and flies, reported Bert, but the Old Man had bought a Victriola and twenty-eight records so they were “expecting some high class music this trip”.

They spent umpteen weeks in Buenos Aires, still struggling to sign enough men to work the ship, and then, two days out of the River Plate and finally underway again bound for Australia, found themselves caught by a pampero.

Suddenly there were hurricane winds and a high, confused sea that churned over and round them. All day they struggled to take in sail, clinging to the yards high above the lurching, rolling decks until, at 9pm, as apprentice Lewis Watkins recalled, the mizzen lower topsail “carried away with a noise like gunshot”.

Watkins was knocked off his feet and down a companionway, breaking his leg in several places, but there was no time for first aid. Every man had his hands full. So the boy was just dumped on his pitching bunk and left, teeth gritted against the pain. All night the men wrestled with the wind and the sails and the sea, and it was not until early the following day that Captain Donaldson, assisted by the carpenter and old Henry Robinson the sailmaker, had a spare hand to cut off Watkins’ sea boot and straighten and set the leg on the still rolling decks. Watkins fainted dead away, he said.

The following six weeks were rather pleasant, at least for him. He spent them in his bunk in the boys’ half-deck, cosy and dry while all hands worked the ship through the Roaring Forties, and he was still enjoying easy duties when Monkbarns arrived in Melbourne at the end of January 1918. At that point, Donaldson called in an Australian doctor – who prescribed re-breaking the leg and resetting the fracture. Recovery was galvanised, and Watkins was back up on the yards with the other boys by the time they sailed again, two months later, bound for New York with flour for the US army.

Eight men deserted in Melbourne and they spent 17 days stuck out in the anchorage fully loaded, ready to sail, while Donaldson tried to find last-minute replacements. Time and again, men signed then failed to appear. “We are still short of four men and a cook,” Bert wrote to his mum on March 5th 1918, “so goodness only knows when we will get away.” The eight who eventually did arrive aboard were “a bunch of stiffs”, according to the apprentices, or as Donaldson put it later “a crew of the most difficult men.”

There was an American, a Peruvian, a Chilean and a Dane, a Norwegian cook, a Welsh former bosun with a good record, and an Irishman who claimed to have spent 30 years in jail. Neither the American nor the Peruvian appeared to have been to sea anytime recently, as there is no date for previous employment against their names in the crew list, and Donaldson’s records show he had to advance them £1 16s each to buy appropriate clothes. The eighth, a Dutchman, pulled a knife on young Watkins the first time they went aloft alone. He had come at him crabwise along the yard, hissing “you’re as bad as those bastards aft,” Watkins said.

Three months later they were all in court, charged with mutiny, in a row that would end Donaldson’s career.

Read on: The mutiny on the Monkbarns

Previously: Friend or foe?

Written by Jay Sivell

July 1, 2010 at 1:06 pm

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Historical postcards, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, WWI

Tagged with AG Course, Captain James Donaldson, handelsmarine, John Stewart & Co, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, marina mercante, marine marchande, Mutiny, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, square rigger, USS South Carolina, windjammer

A sailor’s life – 27. Monkbarns: Captain Donaldson’s tribulations

In New York, autumn 1915, ten seamen deserted Monkbarns, leaving the old windjammer hanging around in the river for nearly two months. Bert Sivell wrote a dozen postcards featuring the South Street seamen’s institute and the mission launch off Liberty Island, but the log tells a different tale. The remaining fo’c’sle hands “liquored” and whored, and the ship’s steward decamped with most of the stores. One man was laid up with venereal disease after only a month in port. From early September to the end of October men trickled ashore and failed to return — Danes, Swedes, Finns, Norwegians, Americans and one Swiss, smuggling out what possessions they might and abandoning the rest. The very last to go, on October 24th, was out-of-time apprentice Geoff Barnaby, of King’s Lynn, Norfolk. He and Bert had signed their indentures together as boys in London four years previously and Bert felt his loss deeply.

Unlike the others, Barnaby’s desertion is not marked in the log with the official stamp of the shore authorities but is written in by hand, after the ship had put to sea, suggesting either that he disappeared at the last minute, or that Donaldson had given him the benefit of the doubt until the matter was beyond mending.

The Old Man was not always so accommodating. After they sailed, one of the new crew was found to be “quite incompetent and totally unfit” and ruthlessly demoted to £1 a month, “unless he shapes up”. The man deserted in Port Adelaide, Australia, three and a half months later, one of seven more to go.

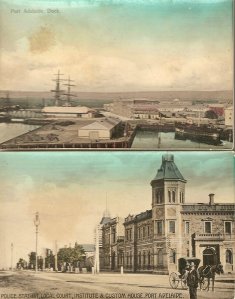

Port Adelaide, Australia, 1916 - Bert sat his second mate's ticket behind the third lamp post, beside the police station. "Very safe"

As they loaded wheat for Cape Town in Port Adelaide, the mate quit and Bert was hurried packed off ashore to sit his 2nd mate’s exam in a building next door to the local police station. Writing home with the news, he discovered his postcard had been printed in Germany, for which he apologised. He still sent it. It did not occur to either him or his parents to tear the card up and write another. He had already paid for it, and the Sivells respected their money.

On the back of the sea-stained indenture paper that went round the world with him, Captain Donaldson had pencilled “Sivell to serve four years. Time expired on 15th August 1915. Signed AB and still on articles 17th February, Port Adelaide,” expanding it ashore with a letter to the effect that he was “diligent, obliging and attentive to his duties, a good seaman”.

In the log, Donaldson wrote:

“Three days have been lost trying to procure substitutes. Then I. Johnson refused to join, and J. Maloney was taken by the military as a deserter from their camp… It cost £3 19s to get R.H. Williams and G. West put on board … which is charged to their account.”

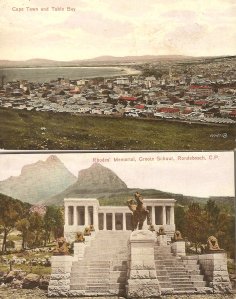

By Cape Town, three and a half months later, drunkenness and insubordination were rife. Two men landed in jail, one twice, and the baldly administrative log becomes quite colourful over the month and a half they were in port loading maize:

Postcard views of Cape Town, 1917 - printed in enemy Germany, Bert Sivell noted (author's collection)

“July 27th 1916, all day. George West who has a rupture of old standing going on shore drinking, coming on board and using insulting language to the master, and going and coming and raging and doing what he thinks fit.

July 31st, 8.30am A. Harris was insolent and insubordinate, and defying the master and mate, went on shore without leave. Also R.H. Williams.

August 2nd, noon R.H. Williams who was on shore the two days previous without leave is now laid up from the effects of liquor.

August 16th, 10am Fritz Jonson returned to work having been absent without leave since 8th inst., arrested same day ashore. Sentenced to seven days in jail. All expenses to be charged to him.

August 23rd, 1pm R.H. Williams returned to work after being in jail and absent without leave from 7th inst. Men were working in his and Jonson’s place, when they could be found to do suitable work. All outlays and expenses will be charged to them.

September 6th, 10 am R.H. Williams returned yesterday after being in jail for another seven days and is again absent without leave, and have been informed by Sergeant of Police that he is to be charged at police court tomorrow. Expenses, etc.

September 12th, 3pm R.H. Williams was put on board by police. His fine and police expenses were paid by the master and will be charged to him.

September 13th, 5pm, Table Bay, George West was taken on board the ship by police in motor launch…”

This is just one page.

In total, the fines, expenses and surcharges came to £7, but on December 11th 1916, two days before they docked back at Avonmouth, Donaldson cancelled the lot “on account of subsequent good conduct”. It was his way. He shied away from “rows” as he called them. Jones, Jonson, Williams and West left Monkbarns without a stain on their record, and went away to plague some other master. Bert, meanwhile, travelled to London to sit his Mate’s exam, with £64 11s and 7d jingling in his pocket. “I wish him success and hope he will (be)come 1st Mate of this ship,” wrote Donaldson.

*

A letter appended to the ship’s agreement offers a tiny personal glimpse of the embattled Old Man. It is addressed to a Board of Trade superintendent, apparently in response to a query about sums of cash Captain Donaldson had advanced to the men who deserted in Port Adelaide. “Sir,” he wrote, as he wrestled with his accounts. “I beg to state that these men kept bothering me for money and threatened to put me into court if I refused it. I gave them the money rather than have a row. Your obedient servant, J Donaldson, Master.”

Eight years previously a seaman had sued Donaldson over pay. He claimed to have fallen from aloft on the ship’s first night out of Middlesbrough, UK, although there were no witnesses and the man had suffered no broken bones or bruises. For four months until they dropped anchor in Fremantle, Australia, the man had refused to work, complaining of pains in his back or his groin or his side, once even under his toes, and with mounting impatience, Donaldson had doctored him, with “salicylate of soda” in accordance with the Ship Captain’s Medical Guide. On arrival in Fremantle however when the seaman, miraculously recovered, demanded to be paid his £17 2s 6d, Donaldson jibbed – and found himself being taken to court. The Old Man lost, and adding insult to injury was ordered to pay costs of £2 8s 6d. Facing trouble in Adelaide in 1916, Donaldson hadn’t wasted his breath seeking help from the law.

Read on: Monkbarns or See-Adler? 1917

Previously: Out of the half-deck

Written by Jay Sivell

June 25, 2010 at 8:03 am

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Historical postcards, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, WWI

Tagged with apprentice, Cape Town, Captain James Donaldson, discipline and desertions, handelsmarine, John Stewart & Co, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, marina mercante, marine marchande, New York, Port Adelaide, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, Ship Captain's Medical Guide, square rigger, windjammer

A sailor’s life – 26. Monkbarns: out of the half-deck

Bertie Sivell was still three months short of the end of his four-year sail apprenticeship when Monkbarns entered the Mersey off Liverpool in May 1915, his first time in a “home” (British) port port in two years. The war that was to have been over by Christmas, wasn’t. His father wrote to the master, Captain James Donaldson, for advice.

“I have nothing to write but what is favourable to your son,” the Old Man wrote back. “He is a smart, intelligent, clever, well-doing lad and there is no doubt he will quickly get on in his profession. If this war was over your son would out-distance eight out of every ten, but at present it is numbers only, no matter what their ability is.”

Donaldson advised against sending the lad back to school for formal training. “He can do all the problems now,” he said, signing off: “With kind regards, hoping he enjoyed his holiday as it will soon be over, yours truly, Donaldson”.

It was not a disinterested response. After four years working unpaid in the half deck, Bert was a skilled hand the elderly master could ill afford to lose. Which was why the end of his indentures that August found Bert back at sea, bound for New York with a cargo of salt. Donaldson put him on the crew list as an Able Seaman at £1 a month, but in fact Bert had taken over as acting 3rd mate on £2 10s a month “as per arranged with the owners,” Donaldson noted on the back of the sea-stained John Stewart & Co contract.

It was to be the start of a rapid career.

Read on: Drunkenness and insubordination – Captain Donaldson’s tribulations

Previously: Monkbarns and Lusitania

Written by Jay Sivell

June 24, 2010 at 12:47 pm

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Historical postcards, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, WWI

Tagged with apprentice, Captain James Donaldson, discipline and desertions, handelsmarine, indenture, John Stewart & Co, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, marina mercante, marine marchande, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, square rigger, war at sea, windjammer

A sailor’s life – 25. Monkbarns and Lusitania, May 1915

It was spring 1915. Europe was at war and the German Kaizer had struck back against the British blockade of German ports by announcing unrestricted submarine warfare: no warning would be issued, said Berlin. U-boats would sink any merchant vessel of any nationality seen to be approaching any British port. As the sailing ship Monkbarns rejoined the steamer tracks across the north Atlantic after a long, hard passage round the Horn from northern Chile, the whole sea around the British Isles was a war zone. But the men and boys aboard Monkbarns didn’t know that. They were more concerned about the dwinding provisions aboard.

From saloon to fo’c’sle, they were hungry. The salt pork and beef in the casks had not travelled well. Eventually even the water was brackish. Leif Asklund described the last rations as mouldy biscuits and pickles and some “slobs” of fat from the meat barrel. As day slipped into day, they ran up flags, signalling to the first ship they saw. But the distant funnels scattered over the horizon, fearing a trap.

Eventually a Scottish steamer stopped and Monkbarns lowered a lifeboat to row across. Young Asklund was one of the oarsmen and recorded his delight at the couple of bags of potatoes they were allowed to buy. As well as other stores, the Scottish captain gave each of the rowers a cigar – a huge treat for men who hadn’t seen any “baccy” for many weeks. He also sent over some newspapers, which was how they learned of the German U-boats preying on merchant vessels off the Irish coast.

By April, 128 days out from Caleta Buena, when Monkbarns finally picked up the pilot outside Queenstown (nowadays Cobh, County Cork), the war had claimed more than 100 merchant ships – sunk or captured, including a British cargo freighter bound for the US to pick up food aid for Belgium.

Harpalyce had been torpedoed despite her white flag and the words Belgian Relief painted in huge letters on her hull. Fifteen men including the master died, and American public opinion — previously mixed about the British tactic of starving Germany into submission — was shocked.

Queenstown harbour was closed off with nets at night but open by day and the Monkbarns fo’c’sle hands were able to buy fresh eggs from a bumboat while they were at anchor; food which, Asklund claimed, the master and mates sometimes had in port but “we others” never got. He also claimed to have seen a periscope near the ship one foggy day, a story my grandfather backed up, but again the old windbag was unmolested.

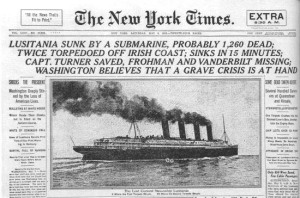

In Queenstown, Monkbarns received orders to continue across the Irish Sea to Garston, near Liverpool, but because of the U-boat attacks she had to wait three weeks for an armed escort. On May 7th 1915, the old windjammer was barely out of Queenstown harbour and still under tow by the Dutch steam tug Zwarte See when it picked up a distress call from the passenger liner Lusitania, five miles away. The apprentice boys on Monkbarns watched the ships steam out of Queenstown past them to pick up the survivors, fully expecting that they might be next, according to their young Swedish crony in the fo’csle. They were, after all, carrying nitrates needed for the war effort.

Lusitania, bound for Liverpool from New York, had been torpedoed without warning and sank in eighteen minutes. More than eleven hundred lives were lost, including a hundred and twenty-eight Americans and nearly a hundred children. The US president was outraged. But neutral America was still not quite ready to enter the war. Germany apologised.

Questions were raised about why such a fast ship, capable of travelling at 26 knots, should fall prey to a much slower U-boat. Why the master was not zig-zagging, and why warnings of three other attacks in the same area in the previous two days were ignored. Two explosions had been heard, and Germany claimed the second was a secret cargo of munitions exploding in the hold. Britain said it was coal dust igniting in the empty bunkers. There were rumours of German spies among the dead.

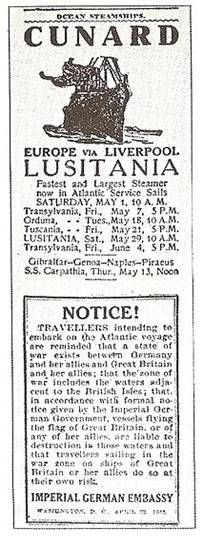

Two weeks previously a warning issued by the German embassy in Washington had run beside Cunard’s advertisements in several US newspapers. “NOTICE!” it read. “ Travellers intending to embark on the Atlantic voyage are reminded that a state of war exists between Germany and her allies and Great Britain and her allies; that the zone of war includes the waters adjacent to the British Isles; that, in accordance with formal notice given by the Imperial German Government, vessels flying the flag of Great Britain, or any of her allies, are liable to destruction in those waters and that travellers sailing in the war zone on ships of Great Britain or her allies do so at their own risk.”

It was widely dismissed. Why, if it was safe enough for the millionaire Vanderbilts, with their connections … (Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt, aged 37, and his valet were among the lost – last seen tying a life jacket to a woman with a baby.)

In the trenches of northern France allied troops were choking on a new deadly green gas. They had no masks, just instructions to “breathe through damp cloth”. British casualties in the war were tens of thousands and mounting.

On arrival in Liverpool, Bertie Sivell went home to his parents. They had not seen him for two years.

Read on: End of indentures

Previously: Monkbarns and the Battle of Coronel

Written by Jay Sivell

June 22, 2010 at 8:36 pm

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, WWI

Tagged with apprentice, Atlantic liners, Captain James Donaldson, death at sea, handelsmarine, John Stewart & Co, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, Lusitania, marina mercante, marine marchande, merchant navy, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, square rigger, war at sea, windjammer