Archive for 2010

A sailor’s life – 23. Deserters, stowaways & sailing to war, 1914

Dr Johnson, from James Boswell’s The Life of Samuel Johnson

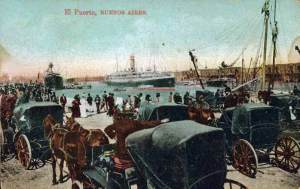

Bert Sivell celebrated his 18th birthday in spring 1913 in Buenos Aires, surrounded by steam ships and bustle and electricity, unloading cement from Greenhithe, London, after 61 days at sea in an ill-lit, unheated square rigged sailing ship – cold, wet, uncomfortable and in Bert’s case, unpaid.

In Buenos Aires, with orders to sail for Australia, Donaldson was struggling. The ship’s papers specified a minimum number of hands needed to work the ship, so the loss of six left him badly short, even after the missing cook was carried back aboard, dead drunk. And then by a stroke of luck, while the ship idled expensively at anchor in the River Plate, two “stowaways” were allegedly discovered. The Old Man didn’t mess about. Both were promptly entered on the articles at £1 per month, and the ship sailed.

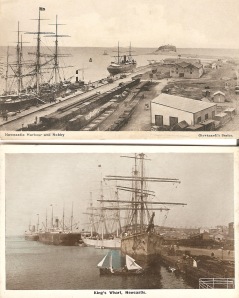

Three months later, in Newcastle NSW, six more men deserted – including the drunken cook. In fact, Asklund recalled, the fo’c’sle emptied, apart from him and two Finnish able seamen. The cook was owed £2 5s 2d, according to the log, but desertions in Australia were considered inevitable because coasting vessels there paid more than the British sailing ships passing through.

Monkbarns spent two months in Newcastle, loading coal, and hunting for crew. There were several British sailing ships in port, including John Stewart & Co’s Lorton, and Monkbarns’ twin Belford, and lots of lads stumbling among the bales and rails along the Dyke at home time. Asklund remembered the Reverend Forster Haire belting out My Old Shako at the mission concerts and Bert sent dozens of postcards showing the Reserve, where they walked, and the beach, where they lolled, and the kippered buildings along the steam tram line in Scott Street. He also sent one of Belford, highlighting his own ship’s superior points.

In the half deck the shortage of hands was felt acutely. Bert recorded that one night the callow mate — himself an out-of-time apprentice — had tried to stop the boys going ashore, to have them on standby to shift the ship off the loading Dyke. “Of course, we objected to that,” Bert wrote. “So we all dressed and all eight of us and our young Swede walked sedately over the gang-way. As we walked back along the Dyke at 10pm in a body we saw the old man and mate talking, so it was look out for trouble. But to our surprise nothing happened. They were waiting for us. It appears that the mate had tried to stop us on his own without the old man’s knowledge. We had been working hard since 3am that morning and it was past midnight before we finished. “

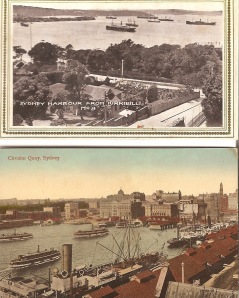

From Newcastle they sailed for Chile, to pick up saltpetre for Durban, South Africa, and from Durban they sailed in ballast – that is empty – back to Australia, arriving nine months after they had left, with another stowaway who had been made to work his passage. In Sydney, four men deserted and two who signed on failed to join. The ship’s boy decided to join the navy. A postcard view of Sydney harbour, strangely bald to modern eyes without the harbour bridge and the opera house, records that Bert and another apprentice took an hour and twenty minutes hard rowing to get the Old Man ashore in the teeth of a southerly gale. They were loading for Chile again, seed wheat this time, and “working like niggers” [sic] he complained. But he “rowed the ladies about” and made friends at the Mission.

They left Australia in early June 1914 and were out in the southern Pacific cut off from everything except the sea and the sky when a young Serb nationalist in Sarajevo shot dead the heir to the Austro-Hungarian empire.

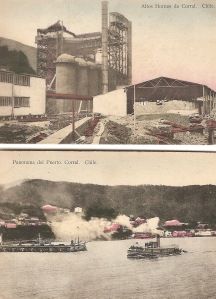

By the time Monkbarns dropped anchor in Corral, on the west coast of Chile, in the second week of August, war was erupting across Europe and beyond like firecrackers. In Monkbarns’ half deck the focus was on business as usual. The fighting was expected be over by Christmas, and Monkbarns would not be off the Lizard, in Cornwall, until the following April at the earliest.

The log records daily lifeboat drills, which was new, and five apprentices were promoted to able seamen, but the ship had been in Chile for two months before Captain Donaldson and “H. Horstmeyer, German,” decided it might be better if the now enemy member of Monkbarns crew were discharged. Even then, Horstmeyer’s wages were properly calculated and paid to the consulate in Valdivia.

“Just a card to let you see that the Germans have not caught us yet,” Bert wrote casually from Corral to his Ma on a view of iron ore smelters. (“Needless to say closed, due to lack of funds.”) Chile was technically neutral, despite its large German community, and his main topic was not the war but a dispute with the owners of the ore works who were claiming 1,000 pesos, or £29, for Donaldson having put a line on their jetty to avoid a collision. It was also raining, he reported.

But war was about to come to the nitrate lanes.

Read on: Monkbarns and the Battle of Coronel

Previously: The nitrate coast, Chile, 1912

Work in progress: the book I never wrote about the sailor grandfather I never knew, from his apprenticeship on the square-rigger Monkbarns to his death by U97, presumed lost with all hands aboard the Shell oil tanker Chama in 1941 Blogroll

Written by Jay Sivell

June 16, 2010 at 6:20 am

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Historical postcards, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, WWI

Tagged with apprentice, Buenos Aires, Captain James Donaldson, desertions, discipline and desertions, handelsmarine, John Stewart & Co, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, marina mercante, marine marchande, merchant navy, Newcastle NSW, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, square rigger, Sydney, war at sea, windjammer

A sailor’s life – 22. The nitrate coast, Chile, 1912

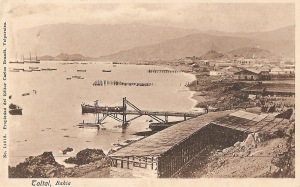

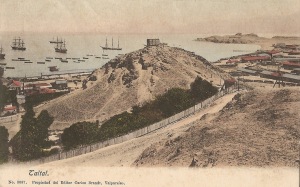

Taltal, in Chile, was a sprawl of single storey houses and sheds clustered round a solitary spire on the edge of the Andes. It was a bleak open anchorage battered by the Pacific, indistinguishable from dozens of other barren little ports strung out along 1,600 km of what became known as the nitrate coast.

Behind them, from Arica in the north to Coquimbo in the south, stretched the Atacama desert, where no rain is said to have fallen for a thousand years. It was once the only known source of naturally occurring sodium and potassium nitrates – saltpetre, as Bert Sivell knew it – fertiliser and explosive for the munitions factories and fields of industrialised Europe. Wars were fought over it. Fortunes were made.

Teeming Iquique, at the northern end of the treeless, dusty strip, had been a small fishing village in Peru when the “white gold” rush started in the 1830s. Foreign capital had poured in, building railways and processing plants and even an opera house, and men had flocked to the desert lands to live out their dreams in mining concessions with names like Adventure, Perseverance and Chance. Bolivia, Peru and Chile fought for control of the rich territory, and Chile won.

By the 1890s there were sometimes a hundred vessels at a time loading in Iquique bay and sailing ships rocked in Chilean anchorages from Talcahuano (known to British sailors as “Turkey Warner”) in the south to tiny bleak Caleta Buena near the new border with Peru. By 1912 Chile was exporting two million tons of nitrates a year.

Monkbarns arrived in Taltal in June and left again at the end of August. In between, all hands discharged their Australian coal and heaved the nitrate – nowadays considered dangerous to actually handle — bag by bag down the hatches for two months. Bert sent postcard views of the exposed bay, the long jetties battered by the breakers, and the cross-hatch of distant roofs and railway lines that petered out into rubble tracks up into the surrounding mountains. Thirty or forty ships heaved and rolled with the swell in lines beyond the surf, as restless as if they were in the open sea.

The nitrate trade was one of the last in which sailing ships could compete against steam. Sailing ships did not rely on expensive supplies of coals and water and so could afford to hang about beyond the sand bars for months while an awkward cargo was ferried out to them slowly, boat by boat. Guano was worse, a throat-catching green powder of ancient bird droppings shovelled off rocky outcrops further north, off Peru, and stowed in the holds by men who could only work 20 minutes at a time before they choked. The crews of guano ships were known to flee into the rigging to escape the ammoniac fumes. But the nitrate was in many respects no better.

Nitrate was white, mined and stewed in the distant desert where no rain falls from one year to the next and until the railways came, carried to the sea by pack mules that died of thirst along the way. It had to be stowed dry. But out in the anchorages, in the holds lifting and falling in the long Pacific swell, the evaporation from the bags was known to kill rats and even woodlice, and ships’ cats who curled up on the sacks in dark corners grew lethargic and died.

Day after day, from six in the morning to six at night, the crews would shovel the Australian coal out through the hatches and tip it basket by basket into the waiting lighters, until the dust grated in their lungs and ground itself into their skin. There would be arguments with the Chilean tally clerk, a stray foot on the scales to mask a bit of pilfering for the fo’c’sle stove, and then finally shanties and cheers as the last basket was hoisted out followed by a well-earned tot of whisky for all hands. But the following day the work would go on, cleaning out the holds before the long, tedious, unhealthy process of stowing the saltpetre began.

It came aboard in bags of 200lbs and was stacked into pyramids in the holds for six weeks by a single stevedore, who could drop each bag into place off his shoulders with absolute precision, never stooping to shift one. Monkbarns took 34,000 sacks, Bert wrote. (About 3,000 tons). The great, beautiful four- and five-masted clippers that set records and made fortunes for AD Bordes of Bordeaux and F Laeisz of Hamburg did the same job with up to 5,500 tons of nitrate in eleven days flat, but they had steam winches – four to a hatch, a small army of cadet officers and shore staff.

Out in the anchorages, the boys from humbler ships made social visits up and down the lines, held sailing races or fished – sometimes with sticks of dynamite, depending how sporting the master was and how much they wanted fresh fish. Even in one-eyed places like Taltal and Caleta Buena there were regularly new faces. Of the 106 sailing ships that left Newcastle NSW for nitrate ports that autumn, according to Lloyds List, a third were British, a third German or Norwegian, and the rest French, Russian, Italian or Swedish. When it was at last time to go, the send-off was exuberant. Home for everyone was round the Horn and language was no barrier.

As the last bag of saltpetre was swung aboard, the smallest boy would leap on it and be hoisted high into the rigging, up and down, for all to see, waving the national flag and bellowing “three cheers for the captain, officers and crew” of whatever ship it might be. There would be answering cheers from each ship in the line, French, German, Finnish, Norwegian or Italian, and at nightfall all would ring their bells, starting with the homeward bound ship, but chiming in until every clapper on every ship in the anchorage was clanging. The din could sometimes be heard for miles out to sea. As it died away the departing ship would solemnly “raise the Southern Cross”, a constellation of lamps lashed to a wooden frame – indicating the direction home.

Then the cheering began again, calling and answering, rippling across the bay. There were chanties and whistles, flaming torches and sometimes – insanely, surely – fireworks. It all took hours, particularly if there was more than one ship preparing to depart. But eventually only the occasional burst of cheering would disturb the sleepy anchorage and ten o’clock would find the homeward-bounder surrounded by work boats, like piglets round a sow. In the saloon, the captain would be entertaining other captains and their wives and shipping people from shore, and in the half deck the apprentices would be doing likewise among the cronies who had rowed their masters over.

Laeisz’s four-masted barque Pamir – the last commercial square rigger to sail round the Horn, in 1949

The following day the ship would sail away to the south-west, turning into the Westerlies towards the ice bergs and the gales and the mountainous seas round the Horn and a three or four month passage home. Bert Sivell arrived back in the UK from Taltal just before Christmas 1912, after a passage of 97 days at sea. Laeisz’s flying “P” line did the trip rather faster – and Potosi set a record of 57 days in 1904 – but demand kept even the smaller, slower ships busy.

The nitrate trade eventually died in the 1930s, after the invention of synthetic ammoniac during the first world war. The last British-registered ship to hoist the Southern Cross was John Stewart & Co’s William Mitchell in August 1927. After weeks in Tocopilla loading saltpetre, her apprentices and remaining crew began to cheer the last bag out – but their shanties met no reply. William Mitchell was the only sailing vessel left in the bay and the dreary steamers and motor ships around her did not trouble even to ring a bell.

Read on: Desertions and war, 1914

Previously: Monkbarns apprentice – Harry Fountain

Work in progress: the book I never wrote about the sailor grandfather I never knew, from his apprenticeship on the square-rigger Monkbarns to his death by U97, presumed lost with all hands aboard the Shell oil tanker Chama in 1941 Blogroll

Written by Jay Sivell

June 14, 2010 at 9:58 am

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Historical postcards, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice

Tagged with AD Bordes, apprentice, Atacama, Caleta Buena, Captain James Donaldson, F Laeisz, handelsmarine, John Stewart & Co, John Thomas North, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, marina mercante, marine marchande, merchant navy, nitrate king, Pamir, Potosi, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, saltpetre, square rigger, Taltal, Tarapaca, windjammer

A sailor’s life – 21. Monkbarns apprentice: Harry Fountain

There was a new crop of apprentice boys in the tin bunkhouse amidships by the time Monkbarns arrived back in Newcastle NSW, Australia, in November 1920, after the end of first world war; new faces in the patchy mirror on the bulkhead and new views of “home” pasted to the walls of each narrow bunk. Many of the old sailing ships had been lost, but not “lucky” Monkbarns.

There were four other British square riggers in port too, they remembered, with 37 apprentices between them, plus boys from the French Champagne and Danish Viking. The Monkbarns apprentices were given the afternoon off to hear a concert at the Seamen’s Mission in Stockton and for most of the next month had time off to lounge about the beach, play tennis and go on picnics with the pretty girls, while they waited for repairs to one of the masts.

“We made our own amusement,” wrote Harry Fountain, in The Cape Horner magazine. “There was probably a theatre, there must certainly have been picture houses, but they were ever beyond us with our few pence. I seem to remember that was soon spent in the Niagara Café on banana splits at 9d a plate.”

Captain Harry Fountain, one of many dozens of boys who passed through Monkbarns’ half deck over the years, served the sea all his life and lived to the ripe old age of 95. What became of “Tich” Copner, Reg Bannister (“who snored like hell”) and the Belgian, Marcel Emil Brough, I never discovered, but Fountain never lost touch with his old shipmate Lionel Walker, who had settled on the other side of the world with the Aussie mission girl he had gone back to find.

Jessie Walker’s family gave me his last known address when I traced them – a damn fool Pom grandchild still doggedly hunting witness accounts of life on Monkbarns three-quarters of a century later – and with typical generosity they heaped on me newspaper cuttings and photographs of the charabanc trips and tennis parties. But my letter to Harry in Boston, Lincolnshire, was returned by his executors: Captain Fountain, retired harbour pilot and sometime pub landlord, was finally at rest under the handsome headstone he had bought and gleefully visited for many years on his daily walk to the docks. He told his local paper the secret of his longevity had been cold showers, bread and dripping, and 20 Senior Service cigarettes a day.

The solicitor put me in touch with one of the old man’s friends. “He would have loved to have talked to you,” they both said. I had missed him by four months.

Read on: The nitrate coast, Chile, 1912

Previously: Pommie boys and Aussie girls, Newcastle NSW 1912

Written by Jay Sivell

June 13, 2010 at 4:23 pm

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Other stories, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice

Tagged with apprentice, first tripper, handelsmarine, Harry Fountain, John Stewart & Co, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, Lionel Walker, marina mercante, marine marchande, merchant navy, Newcastle NSW, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, square rigger, windjammer

A sailor’s life – 20. Pommie boys and Aussie girls, Newcastle NSW 1912

Monkbarns from Nobby's head, Stockton NSW, Australia - the photograph Jessie Walker kept on her wall all her life

From Hamburg that first trip, Monkbarns circled the globe, sailing first across the Atlantic with the north-east trade winds and down the east coast of South America to Santos in Brazil; then south-east through the Roaring Forties and round the Cape of Good Hope to continue in the prevailing westerly winds across the Southern Oceans to Australia. From there, after two months, they moved on eastwards across the Pacific to Taltal on the west coast of South America in Chile, before rounding the vicious Cape Horn backed by the westerly gales again, bound for home.

From Millwall, on the Thames in London, Bert Sivell scribbled a postcard to his pa on December 6th 1912: “Please write soon.” He had been away for a year and four months.

But the log shows the ship had been at sea for only half that – leaving long days in each port while the Old Man struggled to hang onto enough men to work the ship. In Santos, two of the Danes and the Austrian deserted, and after 66 days at sea the boys enjoyed six weeks dallying round the anchorage on the edge of the forest. “Fine bathing here,” Bert wrote.

Monkbarns boys and a Mission charabanc outing, Stockton NSW. Private collection of the Walker family, Australia

In Newcastle NSW, three months at sea later, two more men crept off the ship never to return, and Monkbarns’ log begins to lengthen with Captain Donaldson’s attempts to maintain discipline. Wages in the Australian coastal trade were temptingly higher than anything he could afford to pay, with fewer gales and icebergs.

For the boys, the painting, cleaning and mending continued from 6am till 6pm. Time off ashore (“Liberty” days) were at the Master’s discretion, particularly in South America, where there was a danger of Yellow Fever. But there was usually plenty for the boys to see, even at anchor in the roads, and rowing the officers about was one of the apprentices’ more welcome chores. They had to wait by the boat, rather than go into town, but there were usually work boats from other ships tied up there too and other boys to “yarn” with. Every day brought new arrivals and departures among the thicket of masts.

In Newcastle, Australia, however, beside the picture house and other luxuries beyond an apprentice’s pocket, there was also a lively Seamen’s Mission on the riverfront at Stockton. With a steam launch to pick up all comers, and an army of hospitable volunteers, the Reverend Forster Haire laid on free Sunday teas and concerts and charabanc trips for the visiting sailors. There was dancing, and magic lantern shows — as well as the church services, which the ungrateful young pups ducked out of wherever possible.

In Stockton, big-hearted families who had never seen Europe held open house for apprentice boys from “the old country” with roast beef and Yorkshire pudding, and their tender-hearted daughters lined the breakwater to sob goodbye when they sailed. “Some days you couldn’t get on the breakwater for girls waving goodbye,” recalled Jessie Walker, a former Mission girl, aged 92, tracked down through the library there. Girls wishing to help entertain the sailors were interviewed for suitability, said Mrs Walker.

Jessie herself had married a Monkbarns boy who turned up back on her parents’ doorstep in 1924, blinded in one eye by ice round the Cape. In the nursing home in the converted mission building in Stockton where she ended her days, surrounded by her children and grandchildren and great grandchildren, a photograph of Monkbarns still took pride of place on the wall. Framed against a gathering storm, the ship is frozen in time heading out to sea off Nobby’s Head, where the bonny girls were still waving. Two tiny figures can be glimpsed high up on her yards, busy releasing the sails.

I never met Jessie Walker, or her family, but I can vouch that their generosity and hospitality remained undimmed three-quarters of a century later when I wrote asking for information.

Bert spent two months in Australia in spring 1912, sending home dozens of annotated postcard views of Newcastle and Stockton and a photograph of what looks like himself, sitting among the crowd at the old “tin” Mission with his arm daringly close to a decorous young lady in a large hat. There are pictures of the ships moored along the Dyke, where the coal was loaded; and the beach where the apprentices hung out; and the country estate at Toronto, Lake Macquarie, outside Newcastle, where the hospitable Castleden family went to live.

In a postcard to his grandfather from Newcastle the year after his first visit, when Monkbarns was again in town for two months chasing cargo and crew, Bert wrote “… Last night when we left the mission a large crowd off other ships came down to the wharf to see us off in the launch. As we were leaving they cheered us and the nine of us answered as well as possible. Then we sang “For he’s a jolly good fellow” till we were hoarse. I have never heard any other ship’s crowd of apprentices cheered before, except as last voyage. That shows that the Monkbarns is a very popular ship in Newcastle. Goodbye from Hubert S. Sivell.”

Monkbarns left Newcastle in April 1912, the day after Titanic was lost. The first headlines were just emerging. Loss of life was reported to be great. Bert sent a view of Stockton church ashore with the tug, inscribed only “Just off to Taltal”.

Read on: Too late: Harry Fountain

Previously: Monkbarns and the sail-maker’s palm

Work in progress: the book I never wrote about the sailor grandfather I never knew, from his apprenticeship on the square-rigger Monkbarns to his death by U97, presumed lost with all hands aboard the Shell oil tanker Chama in 1941 Blogroll

Written by Jay Sivell

June 9, 2010 at 12:49 pm

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Historical postcards, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice

Tagged with apprentice, Captain James Donaldson, discipline and desertions, handelsmarine, John Stewart & Co, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, marina mercante, marine marchande, Mission to seamen, Newcastle NSW, Rev Forster Haire, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, Santos, square rigger, Stockton NSW, Taltal, Tin Mission NSW, windjammer

A sailor’s life – 19. Monkbarns & the sailmaker’s palm

Monkbarns sailmaker Henry Robertson and his leather sailmaker's "palm", in the Signal Tower Museum, Arbroath

Arbroath is a brief stop on the railway line that runs down the east coast of Scotland from Aberdeen; a cluster of brown terraces between a ruined abbey and an old harbour wall, beyond which the North Sea growls grey and empty to the horizon.

After nightfall, which is at four o’clock in the afternoon by late October this far north, the smell of wood smoke and fish wafting from open smokery doorways along the waterfront cheers a weary traveller, but the boat yards and slipways that once lined the foreshore are gone and the power looms that once produced 450,000 yards of sailing ships’ canvas a week are silent.

Brothock mill, where James Watt himself came to install the town’s first steam-powered engine as a very old man in 1806, stands empty. The river no longer runs hot with waste from the spinning mills, and the fishwives no longer scrub their laundry at Danger Point where it meets the sea. The forest of masts that brought flax from the Baltic has gone and housing estates have sprung up on the bleaching fields.

Nowadays Arbroath is quiet, a shadow of its heyday as an industrial port, but the mid-week streets are dense with Scotland’s history – the least part of which is the story of the Corsars’ “flying horse” fleet, as it was known to the boy apprentices who would chronicle the last days of sail.

The Corsars were canvas manufacturers, the sons and grandsons of a young handloom weaver who had seen the arrival of Watt’s great spinning engine in Arbroath and liked it so much (in the immortal words of the late Victor Kiam) he bought the mill.

David Corsar senior had started out in a small way, buying yarn from the country folk who gathered in the high street outside the Town House in all weathers every Saturday to sell what they’d spun during the week, and employing other men to weave it into cloth in their own homes. In those days almost every grocer in the burgh had its notice in the window advertising “lint and tow given out to spin”, and the click of handlooms could be heard from tenement windows across the town.

Linen was a cottage industry in Angus, employing whole families heckling and spinning the rough flax fibres to thread, and even the smallest children were set to work winding the yarn onto ‘pirns’ for sale to the merchants who supplied the flax.

Corsar bought his first manufactory in 1823, and despite a wobble three years later, which closed nearly every mill and factory along the Brothock after the banks “in their competition for business offered unwarrantable facilities to men without capital, and many without experience or judgement”– which sounds strangely familiar today – by 1842 there were fifteen mills in the town, and twenty loom shops weaving the heavier canvas in which Arbroath was to specialise. In 1849 Corsar & Sons launched mass production of their top quality Reliance sailcloth, every bolt of which left the Spring Gardens powerloom manufactury stamped with the name, Reliance, over a little flying Pegasus, and to sell it to the shipping industry a merchanting office was set up in Liverpool.

Steadily, more and bigger ships plied to and fro across the Baltic, supplementing the Scottish flax with bales from Russia, Latvia and Estonia, tied with lead seals stamped in Cyrillic letters that are still being dug up today.

D. Corsar & Sons prospered. When the oldest son, William H., died in 1886, the youngest and sole surviving partner, Charles Webster, inherited an estate “valued at some hundreds of thousands, I know not how many,” according to his brother-in-law, a local preacher retained by the Corsars on a stipend of £50 per annum. Three sisters were to receive £10,000 each, and two nephews £4,000.

It was a lot of money. Corsars’ child workers earned 3s 6d a week for a ten-hour day, spent half sweeping floors and replacing bobbins, and half attending Mr Howie’s school on Lordburn. Women mill hands got 5s 3d – and time out to cook the family dinner – and the men 15s. Even a skilled hand “hackler” working at a piece rate of 2s 6d a cwt of imported Russian flax in 1900 could only achieve £1 in a good week.

By the time Charles Webster died, in 1900, he left a fortune valued by the Arbroath Herald at about a quarter of a million pounds, in flax, yarn, cloth, stores, machinery, mills, factories – and ships. Nine ships in all.

The Corsars’ first ship is thought to have been acquired by chance in Arbroath harbour in 1852, possibly in settlement of a debt. But the 174 ton Canadian brig Haidee proved so serviceable on the Australian run that three years later they replaced her with a larger sailing ship, built in Arbroath for trade with the West Indies, and over the years more followed. By 1872, although the family’s main business was still in flax and still in Arbroath, Corsar & Sons had interests in several ships.

In 1884, in what can only be seen as a canny bit of marketing, Charles W acquired two iron-hulled four masters, Pegasus and Reliance. The Corsars’ flying horse line was born.

Over the next ten years, he bought and commissioned more, some with traceable Corsar links such as “WH Corsar” and “Cairniehill”, the family home, and some more obscure. At least to me.

Steam-powered shipping was already cutting the demand for sailcloth, but there was still a living to be made in sail, where the wind was free and labour cheap. Charles W’s last three ships were built in 1895, by which time the view from Cairniehill, Arbroath, was a mass of saw-tooth factory roofs and chimneys. He named the vessels Monkbarns, Fairport and Musselcrag, after Arbroath as it was depicted by Sir Walter Scott in his third Waverley novel, The Antiquary.

The joke – and surely it was a joke – may not have been apparent to the apprentice boys who wrote the final accounts of Britain’s last sailing ships, of which Monkbarns would be one. But they will have understood the nod to literature, and the author of Ivanhoe, because the old sailmaker who helped teach the young officers-to-be their business for the last 14 years of Monkbarns’ sea-going life had grown up in the shadow of Arbroath abbey.

Arbroath to this day is proud of its connection to Scott, (as sacks full of responses from readers of the Arbroath Herald attested when I wrote asking about the names a hundred years after the three ships were launched,) and Charles Webster Corsar was evidently a fan.

The central character in The Antiquary is a crusty old amateur historian known as “Monkbarns”, after his house, modeled on the stately Hospitalfield pile at the entrance to the town. Scott called his town Fairport, and Auchmithie, the abbey’s former fishing village round the headland from Arbroath proper, he named Musselcrag.

Charles W. Corsar could have bought steamers, but the last surviving son of the weaver with the vision to buy Watt’s engine chose instead to build sailing ships, and with a wry flourish he named them after a historical romance.

Sadly, there is no happy ending. In 1911 the Corsar business came crashing down due to an “ill-advised will”, according to one of Charles W’s great-great-grandsons. The premature death of his oldest son, at 44, triggered a clash of trusts and a firesale to protect the girls’ portions.

That March, the Arbroath Herald reported, the old-established firm “which has an honourable place in the history of Arbroath” went into sequestration due to a falling out between the heirs. “Gratifyingly” there were no trade creditors, it said, but 400 workers faced unemployment and “it is hardly likely that the beneficiaries under Mr Charles Corsar’s settlement will receive anything like the provision he hoped to make for them”.

A bankruptcy hearing in April was held in private, but the Herald was able to print the full list of assets and liabilities: three spinning mills, the weaving factory, a bleachworks, three warehouses and a waterproofing plant, plus stock, including the counting-house furniture and sundry investments, were valued at £153,220.

Unfortunately the liabilities left a deficiency of £22,312 (and 16s 7d), including £25,000 left to each of Charles W’s three daughters, trusts totalling £81,000, a mortgage on Monkbarns, and a £31,000 contingency fund set aside for litigation involving two other ships, Gunford and Chiltonford.

Corsars’ shipping ventures offer a snapshot of the times. Princess Alice had been wrecked in 1872; George Roper went down on her maiden voyage outside Melbourne in 1883 – due to tug error; Cairniehill suffered a mutiny in 1895 and was sunk by fire in New York in 1896; WH Corsar was wrecked in 1898; Glencaird was stranded off Staten Island in 1901; and Reliance burnt out loading saltpeter at Iquique in 1907. Even Monkbarns had her troubles. In 1906 she was stuck in ice round the Horn for three months, visible to passing ships but beyond reach of all assistance, and her captain died there. Then, in 1910, the new master, James Donaldson, collided with a German ship in Iquique in Chile, damaging the famous flying horse figurehead and unleashing more litigation when the ship docked at Hamburg.

Gunford meanwhile had run into a reef off Brazil in 1907 and been lost. Or rather, she ran into three reefs, over several days for reasons which were not clear because the relevant pages of the ship’s log were subsequently “stolen by pirates”, according to her captain. The ship had not made a profit for several years and was found to have been heavily over-insured, not just by the owners (which was deemed legitimate) but also – and privately – by the ship’s manager, which was not.

There was an inquiry at which the captain, an elderly German who had not been to sea for 22 years, lost his licence for a year. But a court hearing in 1909 eventually ordered the insurance company to pay up. Deliberate wrecking was hard to prove. The case was taken up in the House of Lords, resulting in a change in maritime law, and was still rumbling on in 1911 when the Corsars went bust.

By then, Fairport, Musselcrag and Pegasus had “gone foreign”, and Almora and Chiltonford were limited companies under new management. The Corsar mills and plant were sold that June, and the firm was taken over by a Glasgow company.

Monkbarns – still laid up in Hamburg – was sold to John Stewart & Co of Dundee for £4,850. And by August 17th eight new teenage apprentices had stowed their sea chests in the cramped half deck and taken the first creases out of their brand new dungarees.

In Arbroath, a scrap of reinforced leather lies on a glass shelf under a photograph of an old man stitching in the sun on Monkbarns’ deck. Henry Robertson, aged 52, of 24 Allan Street, Arbroath, joined the ship the same day as Bert Sivell, aged 16, from Ryde, and after a lifetime at sea lies buried up the coast in Sleepyhillock cemetery, Montrose.

His leather sailmakers “palm” in a glass cabinet in the Signal Tower museum, Arbroath, is the last surviving tangible link with Monkbarns.

Read on: Pommie boys and Aussie girls, Newcastle NSW 1912

Previously: Corsars’ flying horse figurehead

Work in progress: the book I never wrote about the sailor grandfather I never knew, from his apprenticeship on the square-rigger Monkbarns to his death by U97, presumed lost with all hands aboard the Shell oil tanker Chama in 1941 Blogroll

Written by Jay Sivell

June 8, 2010 at 8:56 am

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Sailing ship - Monkbarns

Tagged with apprentice, Arbroath, Corsars, Fairport, Haidee, handelsmarine, Isle of Wight & Sivell family, John Stewart & Co, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, marina mercante, marine marchande, merchant navy, Musselcrag, Pegasus, Reliance, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, sailmaker's palm, Sir Walter Scott, square rigger, windjammer

A sailor’s life – 18. Corsar’s flying horse figurehead

Monkbarns' flying horse figurehead - built to advertise Corsars' sail canvas, (private collection, Australia)

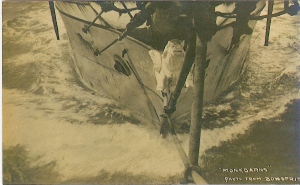

Monkbarns was a wet ship. Even in moderate seas timber breakwaters had to be put up to shelter the door to the officers’ accommodation aft as a foot of water ran up and down the deck. The steward carrying the master’s dinner from the galley amidships during a “blow” had to dodge up on to the poop deck and down the companionway (stairs) by the wheel, greatly to the glee of the crew who kept their own feet dry by balancing on the pin rails where the ropes were fastened.

She had been built in 1895 in Dumbarton, Scotland, one of three off-the-peg iron-hulled sailing ships commissioned by a flax mill owner from Arbroath with romantic leanings and canny notions about commercial branding somewhat ahead of his time.

Charles Webster Corsar was a large jolly man, a pillar of the church and community, often to be seen striding between the frames and looms of his family’s steam-driven mills, his coat snowy with the choking clouds of flax dust. Monkbarns was a cargo carrier, an ocean-going freighter built neither for speed nor beauty, yet he gave her fine teak fittings, a handsome saloon, and reportedly every labour-saving device available for working cargo and sails, except a powered winch. He even provided comfortable accommodation for the fo’c’sle hands. But what made his ships memorable to dockside loungers around the world were the tiny white winged horse figureheads on their prows.

Corsar & Sons had been founded in the early 19th century by a handloom weaver who had seen James Watt set up the first mill engine in the town in 1806 and went on to buy it. Charles Webster was a younger son who had entered the business in the shadow of older brothers, but by the time he was senior partner, the family owned some 60,000 to 70,000 spindles, hackling, spinning, bleaching and weaving flax from the Baltic into yards of Reliance sailcloth that carried the name of Corsar around the world, stencilled onto each bolt over the image of Pegasus, the flying horse.

Read on: The sailmaker’s palm

Previously: The devil provides the cook

Work in progress: the book I never wrote about the sailor grandfather I never knew, from his apprenticeship on the square-rigger Monkbarns to his death by U97, presumed lost with all hands aboard the Shell oil tanker Chama in 1941 Blogroll

Written by Jay Sivell

June 7, 2010 at 6:52 am

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Historical postcards, Sailing ship - Monkbarns

Tagged with Corsars, figurehead, handelsmarine, John Stewart & Co, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, marina mercante, marine marchande, merchant navy, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, square rigger, windjammer

A sailor’s life – 17. The devil provides the cook

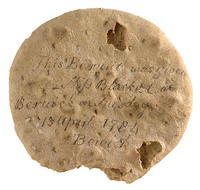

Ship's biscuit, presented to a Miss Blacket in 1784, from the collection of National Maritime Museum Greenwich

Imagine if you will a world without cheese, or milk, or apples, or even a carrot or cabbage leaf. Imagine day after day, tin pannikins with the same boiled salt meat and dried pulses, uniform brown, with never a hint of tomato, unrelieved by soft bread or clean water.

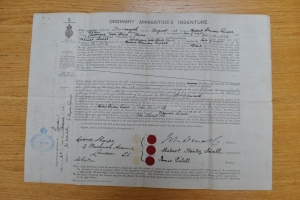

The sailing ship indenture Bert Sivell signed in August 1911 specified that John Stewart & Co were to provide “sufficient” meat, drink and lodging. But “sufficient” is a subjective term.

The provision of food in British merchant ships was regulated by the Board of Trade and a scale was printed in the ship’s articles where all aboard might read it, forestalling argument. But there was a saying in sailing ships that while God provides the food, the Devil provides the cook.

Vegetables and fruit lasted about a fortnight after leaving port, fresh milk and butter rather less. Thereafter – possibly for months on end until the next landfall – there were sacks of rice and flour and split peas, and casks of meat, and evaporated milk and butter in tins.

The Board of Trade stipulated masters should provide each man with a quart of water and a pound of salted pork or beef a day, which was usually served on alternate days with pea soup or rice or (weather permitting) bread, and whatever was left over appeared again for dinner. All quantities were strictly laid down: a pound of bread daily, 1/4 lb rice twice a week, 2 oz of preserved potatoes three times a week, and 2/3 pint of peas. The agreement even detailed acceptable substitutes — a pound of ship’s biscuit in the absence of flour, 1/4 oz of tea instead of 1/2 oz coffee beans.

Tea, coffee beans, sugar, marmalade, butter and condiments were distributed as weekly stores for individual use and safekeeping, and again in the quantities strictly laid down by the Board of Trade.

Although bigger ships might carry chickens and a couple of pigs, they too were prey to the weather, and after ten days on salt meat British masters were legally obliged to serve lime juice, to prevent scurvy, which made your gums swell and your teeth fall out. “Limeys,” jeered American crews. By his mid-twenties Bert needed false plates top and bottom.

Meat on Monkbarns was kept, unrefrigerated of course, in casks of brine below decks and tipped into a locked, iron-bound teak harness cask on deck abaft the mizzen mast as needed. There, it warped in the wet and heated in the sun until the surface ran with all the colours of the rainbow and “care was needed in passing to leeward if you were fastidious”. It was served, boiled with dried potatoes and beans, as wet hash (stew) or dry hash (cottage pie), or sometimes as curry with rice or “Boston baked beans” (in molasses).

On Sundays, as a treat, there was tinned meat and “duff” – plain suet with molasses. And on cold days there was “burgoo” or oatmeal porridge, galley fires permitting. But everything was prone to decay.

Drinking water went brackish in the sun and weevils soon wriggled in the flour, the oatmeal, and even in the hard tack or ship’s biscuits, which were three-inch squares triple-baked to a rock-like dessication that was supposed to ensure they “kept” for five years. The trick was to tap them on the table so the beetles fell out and then soak them in coffee, Bert told his son. He had little sympathy with children who would not eat their sprouts.

In the half deck the growing apprentice boys, always hungry, obsessed about food. Cracker hash and dandy funk were favourites, both featuring biscuit (less “the more obvious weevils”) crushed with a belaying pin, and then either mixed with chopped pork and lard, or with brown sugar, marmalade and a dab of butter. Baked on tin plates by stealth in the galley when the cook’s back was turned the result was, one elderly seadog wrote mistily, “a magnificent delicacy particularly suitable for afternoon tea on Sundays, provided, of course, you are on board a square-rigger bound for Cape Horn.”

As the weeks stretched into months at sea, the packages of little comforts packed by the mothers far away slowly emptied and the new dungarees began to sprout rents and patches. Saltwater boils erupted on necks and wrists from the chafing oilskins, and the daily scrubbing wore calluses into hands and knees.

From the bridge of his Shell oil tanker, not so many years later, Bert acknowledged the past discomforts. “One night,” he wrote, “I think it was last Tuesday, some very heavy squalls came along when I was on watch, accompanied by torrential rain. While they were on I just looked up aloft and smiled to myself that there were no sails up there to be looked after. I kept that watch on the bridge without oilskins or sea-boots and at midnight when I was relieved I was as dry as a bone … and people wonder why they can’t get officers for sail.”

Read on: Corsars’ flying horse figureheadPreviously: Learning the ropes

*Victor Fall and Harry Fountain, ex-Monkbarns apprentices

Written by Jay Sivell

June 6, 2010 at 9:34 am

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Sailing ship - Monkbarns

Tagged with apprentice, cracker hash, dandy funk, first tripper, handelsmarine, hardtack, John Stewart & Co, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, marina mercante, marine marchande, merchant navy, pound and a pint, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, ship's biscuit, square rigger, Tall ships, windjammer

A sailor’s life – 16. Monkbarns: learning the ropes

Bert Sivell recorded that he had arrived on board Monkbarns on August 14th1911, but the ship did not sail until the 22nd. In between, the new apprentices were “learning the ropes” – essential for working an unlit sailing ship at night in a storm when the wrong move was life and death. Everyone — even the cook — had to know the ship’s gear by feel, from the layout of the belaying pins where the running rigging was fastened, to the hemp edging identifying the back of the square sails. If a boy did not know the ropes, if he slackened or hauled on the wrong one in the blackness, he risked drowning them all.

Being neither officers nor crew, and unpaid to boot, apprentices were given all the nastiest jobs aboard, from polishing the brasswork to sanding the deck every morning on hands and knees. Bert spent the first week painting and cleaning, loading food and canvas, and working as a stevedore before the hired hands turned to. But off watch, in the boys’ rank dank little glory hole amidships, squatting on their shiny new sea chests, there were yarns and horseplay and friendships were struck up that would last a lifetime.

Out at sea, the chipping and greasing and swabbing and pumping continued unabated, at the beck and call of the Mate, or chief officer. The boys had to strike the bells on the poop that kept the ship’s time and heave the log, which measured speed and drift, and keep the compass binnacle (the stand) polished and the oil in the lamps topped up. They scrubbed the decks with great ‘holystone’ blocks for hours at a stretch until their backs and knees ached, to prevent the timbers becoming slippery, and sluiced them with salt water to prevent shrinkage.

When there were ropes to be hauled on* [As any fule kno, there is in fact only one rope on a ship, and it is attached to the ship’s bell, the rest are halliards, braces, lines and hawsers, see below, Ed.], the boys pulley-hauled behind the crew and coiled the ends away. They helped take in sail and let out sail, and learned rapidly to jump aloft in all weathers and at all hours, feet splayed along the wires slung under each swaying yard, to grease a mast or slacken off the lines that gathered the canvas “bunt”, to prevent the sails chafing.

Within weeks they were clambering like monkeys, high up among the sails beyond the last tarred rope ratline, from where the ship far below looked like a blade cleaving the sea.

Read on: The devil provides the cook

Previously: Why would you?

Halliards haul up yards, braces swing yards, clewlines haul up the clews or corners of sail to the yard, buntlines gather the body or bunt of the sail to the yard, hawsers are for mooring. Some would say the ship’s bell hasn’t a rope either but a lanyard…

Written by Jay Sivell

June 5, 2010 at 9:29 am

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Sailing ship - Monkbarns

Tagged with apprentice, Corsars, first tripper, handelsmarine, John Stewart & Co, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, marina mercante, marine marchande, merchant navy, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, square rigger, windjammer

A sailor’s life – 15. Why would you?

The story in the family was always that Thomas Sivell, master carriage builder of Ryde, on the Isle of Wight, had packed his only child off to sea in sail to put him off sailoring once and for all. But it would appear the family was wrong again.

Life on the windjammers was cold and hard and dangerous, and no doubt a cruel shock after a year as a flunky on passenger ships. While steamers ate up the miles in straight lines across the ocean, sailing ships tacked and tossed at the will of the wind. They could not sail through Mr De Lesseps’ canal at Suez, linking Europe to the Far East, nor through the new canal being built at Panama to open up the Pacific. Instead, they fought their way south round the Horn and the Cape of Good Hope, adding thousands of miles and months of dangers to their journeys. Ships were lost and boys were killed, but as a training it was considered second to none.

Thomas paid £10 for Bert’s apprenticeship because Thomas was investing in gold braid.

Hindsight proves him right, too. Up to the first world war steam ship companies like Cunard and White Star, with the biggest and most modern engines, sought their officers only among those with experience in sail. The demand outlasted the ships. The Thames and Hull pilot services only dropped the requirement in the 1930s, by which time most of Britain’s sailing ships had been sunk or sold “foreign” to the Baltic and South America, and junior British officers were having to ship with foreign vessels to comply.

If Thomas did quietly harbour hopes of ill-winds, as my father believed, he got more than he bargained for. For the first world war broke out before the end of Bert’s four year apprenticeship, and Monkbarns was to go down in history as the last British commercial square rigger to suffer a mutiny.

Read on: Learning the ropes

Previously: Monkbarns apprentice

Written by Jay Sivell

June 4, 2010 at 3:10 pm

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice

Tagged with apprentice, Cotton Palmer Sivell, first tripper, handelsmarine, Isle of Wight & Sivell family, John Stewart & Co, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, marina mercante, marine marchande, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, square rigger, Tall ships, windjammer

A sailor’s life – 14. Monkbarns apprentice

Day after day and night after night there was nothing round the ship but the howl of the wind, the tumult of the sea, the noise of water pouring over her deck. She tossed, she pitched, she stood on her head, she sat on her tail, she rolled, she groaned, and we had to hold on while on deck and cling to our bunks when below…

From Youth, Joseph Conrad, published 1902

In 1912, the year Titanic sank with her band playing and the men deep in her engine room drowning to keep the electric lights blazing across the icy waters, Monkbarns was a throwback to a darker age.

Lit only by the smelly kerosene lamps that lurched in the cramped living quarters fore and aft, Monkbarns had no generator to winch cargo or weigh anchor, no auxiliary motor, refrigerator or Marconi. She had no great steam boiler growling in her bowels fed by a mountain of coal and a dozen stokers, condensing drinking water and drying wet clothes as it pushed them onwards across the sea. On Monkbarns the only sources of heat were a couple of cast iron bogey stoves and the coffee pot bubbling on the galley fire — until the cook chased you away. Down among the narrow bunks where the men off watch ate and slept, from the crew in the cramped fo’c’sle — where the waves boomed and crashed under the bows — to the officers in the cramped saloon aft, the ship reeked of wet oil skins, Stockholm tar, pipe smoke, and the dank straw mattresses known to sailors as donkey’s breakfasts.

It was a groaning, moaning, banging world 267 feet long and 23 feet wide, contained within a squat rust-streaked hull and dominated by three masts festooned with hemp and steel lines and wooden spars. Overhead, acres of weather-beaten canvas strained and slapped, tearing muscles and ripping fingernails to the bloody quick.

There was a raised deck fore with the anchor and a raised deck aft with the great wheel, open to the winds, and in between, set apart from both the men and the masters, two deck houses, one for the apprentice boys and one for the “idlers”: the cook, the sailmaker and the ship’s carpenter. Below them and sometimes stacked around them, was the cargo: wood or grain or coal or wool, but always “saltpetre” (nitrate) back.

When Monkbarns left Hamburg bound for Santos, in Brazil, on Bertie Sivell’s first trip, there were 14 men in the fo’c’sle, mainly Germans, Danes and Swedes, plus a Finn and an Austrian, and Bert was one of nine gangly apprentices in the boys’ house, conspicuous in their crisp new dungarees. Although the ship was Liverpool registered, only the boys and the young 1st and 2nd mates were English, and not all of them. At 16, Bert wasn’t the youngest aboard either. The senior apprentice was 21, but the Old Man – who wasn’t a bad old stick – promoted him out of the half deck as 3rd Mate on Christmas day, the log records.

The “Old Man” was a Scot, Captain James Donaldson of West Kilbride. Ship masters are always known to their men as the Old Man, no matter how young they may be, but Monkbarns’ Old Man was old indeed; a tall, thin, stiff, white-haired giant of 62, gaunt and craggy after half a century at sea. The son of an Ayrshire coal miner, he had started in coasting vessels at 17 and worked himself up the hard way through the fo’c’sles of deepwater traders.

By 1912, James Donaldson had been a master in sail for 36 years. But he had evidently not forgotten what it was to be young, for he kept a wind-up gramophone and a few records in the saloon for Sunday afternoons at sea, when his apprentices washed their socks and smalls. There had been a Mrs Donaldson, but the boys the Old Man trained did not recall her later when they themselves were old Cape Horners recounting for posterity their tales of the Monkbarns years. But they remembered their old master with respect and affection, as a “gentleman of the old school”.

And the old school in square riggers was tough. Officers, men and apprentices alike lived in two “watches”, working four hours on and four off day and night, night and day, except for two hours between 4pm and 8pm when they ate their evening meal, and swapped over. Their lives were measured in half-hourly bells, one to eight, telling through the day from black coffee and hard tack at 4am to the graveyard shift at midnight and on to 4am again. Week in week out, miles from land, through sunshine or fog, eight bells sounded the weary end of one watch and the bleary start of another.

In heavy weather, of course, there was no routine and no rest, only the imperious cry of “all hands!” and the urgency of taking in or letting out sails, dragging the yards round to change tack, and the kick of the great steering wheel aft which could break the helmsman’s arms and knock him flying across the poop.

Then, the teenagers clinging spray-drenched to the yards 80 feet above the pitching deck, fighting the bellying canvas with frozen fingers, swiftly learned the first rule of sail, which was “one hand for the ship, one for yourself”. There were no safety harnesses or carabiners. Like the Alpinists of their day, if they let go, they fell off, and once overboard they would swiftly be swept from view.

It was not always possible to turn the ship in heavy weather, nor to risk lifeboats and more lives. Mountainous seas can hide whole fleets let alone a bobbing head and flailing arms. Seamen often deliberately did not learn to swim, to ensure the end was quick.

Read on: Why would you?

Previously: Apprenticeship

Written by Jay Sivell

June 3, 2010 at 2:58 pm

Posted in 2. Last days of sail, 1911-1919, Sailing ship - Monkbarns

Tagged with apprentice, Captain James Donaldson, Corsars, first tripper, handelsmarine, John Stewart & Co, koopvaardij, last days of sail, life at sea, marina mercante, marine marchande, merchant navy, Sailing ship - Monkbarns, Sailing ship apprentice, square rigger, Tall ships, windjammer